The Killing Game

Produced by Gayane Keshishyan

"48 Hours Mystery" brings you the story of Rodney Alcala, which is the last story reported by the late Harold Dow. Dow was a "48 Hours" correspondent for 22 years - as long as "48 Hours" has been on television. His passion and his generous spirit are deeply woven into the fabric of this broadcast. He had spent more than a year working on this story, and was determined to bring this intricate tale to our viewers. He was just finishing it when he died suddenly on Aug. 21, 2010.

"I was out doing my patrols. We just started our shift that day. I was driving down Sunset Boulevard. And I had received a call," Los Angeles Police Officer Chris Camacho recalls of that September morning in 1968. "A beige colored car with no license plates was following this little girl."

"Tali Shapiro was an 8-year-old girl walking to school back in 1968," says Orange County Deputy District Attorney Matt Murphy.

"A good Samaritan, a witness, sees the little girl, the little 8-year-old Tali get in the car. Thinks it's suspicious… follows him and puts a call into LAPD," says Los Angeles Detective Steve Hodel.

"I went to that location," Camacho recalls. "And I started knocking. I said 'Police officer. Open the door. I need to talk to you.' This male appeared at the door.

"I will always remember that face at that door - very evil face.

"And he says, 'I'm in the shower. I gotta get dressed.' I told him 'OK. You got 10 seconds. Open this door I want to talk to you.' Finally, I kicked the door in.

"The image will be with me forever… We could see in the kitchen there was a body on the floor, a lot of blood."

"They say a picture says a thousand words," Murphy says, "and that image of those little white Mary Janes on that floor with that metal bar that he used to strangle her with… and that puddle of blood, it just looks like too much blood to come out of - a tiny little 8-year-old like that."

"She had been raped. There was no breathing… I thought she was dead. We all thought she was dead," Camacho recalls. "So I grabbed a towel and I picked up the edge of the bar and I - I laid it off to the side."

"We started searching the residence… there was a lot of photograph equipment," Camacho continues.

"All of us were amazed at the amount of photographs he had there of young girls, very young girls.

"We found - a lot of ID, picture ID of a Rodney Alcala. He was a student at UCLA - an undergrad student."

"That's one of the first times he ever turned up on the radar for law enforcement," Murphy says. "Rodney Alcala managed to give them the slip."

"Unfortunately," Camacho explains, "the other officers - when I kicked the front door - came running around to assist me and - the suspect went out the back door."

But moments later, when Camacho walked back into the kitchen where Tali was, he witnessed a miracle.

"She was gagging and trying to breath. And I thought, 'One for the good guys.' She's gonna make it."

Clinging to life, Tali was rushed to the hospital.

"Had it not been for that police officer, Tali Shapiro would have died on Rodney Alcala's kitchen floor," says Orange County Deputy D.A. Matt Murphy.

"When I was in Vietnam… and we were in combat I was trying to save this guy… and didn't do it. He died," he tells Harold Dow. "So with Tali, it was kind of like God gave me a second chance to save someone."

Soon after Tali healed, her parents moved her out of the country.

"I found out that they had moved to Mexico, that they did not wanna raise the daughter in this society any longer. And that was the last I heard of them," says Camacho.

The investigation was now in the hands of detectives. With Alcala in the wind, Los Angeles Det. Steve Hodel was grasping at thin air.

"All kinds of rumors. He'd gone to Mexico, he'd gone to Canada. He'd gone to Europe. But we kept coming up empty," Det. Hodel explains. "Back then, you know, we didn't have a lot of the forensics you have today."

Complicating matters, it seemed no one was willing to believe the gifted student could be responsible for such a heinous crime.

"He was a snake charmer," Hodel says. "I went and talked to his professor at UCLA. He says he wouldn't harm a fly… he truly believed that, you know. And a lot of people did."

Hodel says investigators went to the FBI. "…we said, 'This guy is going to commit other crimes, he's not going to stop."

In 1969, the FBI put Rodney Alcala on its Most Wanted List.

"We've got to find this guy, we've got to get him off the streets, we've got to bring him to justice," says Hodel.

Nearly two years later came the break they'd been waiting for.

"Two girls went to their local post office… and they looked and there was Rodney Alcala's photo - on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted List. And they looked up and said, 'Oh my gosh, that's Mr. Burger," says Murphy.

The girls knew Alcala as John Burger, their counselor at an all-girls summer camp in New Hampshire.

"They report it to the dean. …he calls the authorities. They arrest him, take him into custody," Hodel says. "I get a phone call from the FBI saying, 'We've got your man in custody, he's ready to be picked up.'"

In fact, Rodney Alcala had been hiding in plain sight for the last three years.

"Rodney Alcala, after raping and almost killing Tali Shapiro, he fled to New York," Murphy says. "He made friends, he charmed people. He got into NYU film school. And he was living the life, kind of Bohemian lifestyle of a film student in the early 70s."

In August 1971, with Alcala finally in custody, Det. Hodel had a chance to speak to him.

"I ask him, 'So tell me about the Tali Shapiro incident.' And basically he says, 'Oh, I want to forget all about that.' He said, 'I don't wanna talk about things that Rod Alcala did.' As if it was a different person."

But with Tali living abroad and unavailable for trial, prosecutors had no choice but to enter into a plea agreement.

"Part of the problem for the prosecution back then is that Tali Shapiro's family had relocated down to Mexico," Murphy explains. "So I think that created logistical problems for the D.A. back then."

In 1972, Alcala pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of child molestation.

"He ultimately was convicted of child molest," Murphy tells Harold Dow. "He received one year to life in the old indeterminate sentencing laws. One year to life and the parole board let him go after 34 months. … after what he did to Tali Shapiro."

Indeterminate sentencing meant a parole board, not a judge, would determine how much time an inmate actually spent in prison.

"The emphasis was on rehabilitation back then," Hodel explains. "And he was able to charm psychiatrists just like he charmed his victims. This guy should've never been released based on the crime itself."

Less than three years later, Rodney Alcala was a free man again. Murphy says he had no trouble charming his way back into the swing of things.

"He got jobs. He was hired by the Los Angeles Times as a typesetter… he took photos at weddings," he says. "And he was a registered sex offender during all of that, and nobody ever checked."

Rodney Alcala was even a contestant on TV's "The Dating Game" and was chosen by the bachelorette.

The decision to release Rodney Alcala would have catastrophic consequences.

"His thrill is seeking his prey, capturing, torturing, hurting. He's a sadist of the highest order," says Hodel. "What he learned in prison was I'm not going to let my victims live."

It was the spring of 1979 in Southern California, and the disco era was in full swing. But in Huntington Beach, 12-year-old Robin Samsoe enjoyed far simpler pleasures.

Bridget Wilvurt was Robin's best friend.

"We just lived to have fun," Wilvurt tells Harold Dow. "Everybody could be complaining about being bored, and me and Robin would find ourselves doing cartwheels and back walkovers."

The other love of Robin's life was her mom, Maryanne.

"She was probably the most loving child a mother could have. Everything she did, she did to please me," she says. "I loved her warmth."

And Robin was the little sister her older brothers, Robert and Tim, doted on.

"She loved ballet, she loved dancing, she loved gymnastics," says Robert.

"She was the glue to the family," says Tim.

"She was my best friend," adds Robert.

On June 20, 1979, Robin was going to start her first day of work answering phones at the ballet studio in exchange for lessons. But first, she planned to play for a few hours with Bridget.

"She arrived at my house at about, gosh, I want to say 11. How much fun can we have during that time?" she says. "Then, I had a great idea. Let's go down to the beach and have a cartwheel competition."

Shortly before 3 p.m., the girls left Bridget's apartment and headed across the Pacific Coast Highway to the beach.

"I could definitely see a gentleman with dark hair," Bridget tells Harold Dow. "He honed in on us, like a shark in the water, honing in on a seal.

"He goes, 'Can I take your girls' pictures? I'm, you know, in a photography class, or for a photo contest.' And Robin goes, 'Sure!'

"And all of a sudden, out of nowhere, pops up Jackie Young, my neighbor. She goes, 'Bridget, is everything OK? Are you girls alright?' And man, he took that camera, turned his head down, and you could almost see, like, smoke comin' off his dress shoes. He just - he was gone."

Shaken, Robin and Bridget turned to go back home.

"Robin had thrown her beach towel and everything into her bag," Bridget continues. "And she's like, 'Well, I'm gonna get going.' And I go, 'Well, take my bike. Take my bike. It's right downstairs. Take my bike and don't stop.'"

That was the last time anyone saw Robin. When her ballet teacher called to say she hadn't made it to class, her family immediately called 911.

"She was supposed to be home - 4:30, 5:00 from her lesson. We spent the next - I did anyway - hours and hours ridin' up and down the path," Tim says of his search for his sister on his bicycle.

The hours turned into days and Robin's mother feared the worst.

"It was probably the most horrifying time of all, you know. Not knowing," says Maryanne.

Police continually questioned the one person they thought might know where

Robin could've gone: her best friend, Bridget.

"And I said, I go, 'It was the man, that man that took our picture,'" she says. "I really was the only person that could tell you the exact color of his eyes, the height of his cheekbones, the color of his skin, just every detail."

On July 2, 1979, 12 days after Robin last said goodbye to her friend and rode off on her bike, detectives showed up at Maryanne's door and delivered the news no one wanted to hear-Robin's body had been found.

"I said, 'Let's go see her'," Maryanne recalls. "He said, 'We can't do that.' I said, 'That's my baby, Of course I can see her. Why not?' He said, 'Because it took us three days to identify her.' I said, 'What's wrong with you people? How many little girls with long blond hair disappear that it took you three days?' He shook his shoulders and the tears were coming down his face, too. He says, 'There was no hair,'" Maryanne tells Dow.

A fire crew conducting routine fire prevention maintenance had found Robin Samsoe's remains in a remote location more than 40 miles from where she was last seen. Orange County D.A. Matt Murphy has visited the site many times.

"Robin had been up here for 12 days before her body was found," Murphy tells Harold Dow. "And there were 12 days for the animals to scavenge Robin's remains, and also for the decomposition to take place. By the time the fire crew actually found her body, she was just bones."

The pressure was on to find the killer. Bridget's description resulted in a composite sketch, which was released to the media all over Southern California.

Murphy says, "His parole officer saw that and called the detectives and said, 'Look, there's a guy that used to be on my case load - you really need to take a look at him. His name is Rodney Alcala.'"

It had been nearly 11 years since Alcala had left 8-year-old Tali Shapiro for dead, and almost gotten away with it. But Alcala was easy to find this time. He lived with his parents in Monterey Park, a stone's throw from the mountains where Robin's remains were located.

Beth Kelleher was Alcala's girlfriend at the time.

"Rodney Alcala is an intelligent - well-mannered, pleasant, fun, outgoing, great individual," she tells Dow.

When asked if she was in love with Alcala, Kelleher replies, "Yes."

Beth was 22 when she met Alcala in the spring of 1979. They shared a common interest in photography.

When Dow asked what she thought about his photography Beth replies, "I saw a lot of pictures of girls."

"Young girls?" Dow asks.

"Ah, young girls, I'd say probably from 12, 13 to probably about 30s," she replies.

Before meeting Beth, Rodney Alcala charmed other women. He was Bachelor No. 1 in a September 1978 episode of "The Dating Game."

"That's a perfect example of the charm of Rodney Alcala," Matt Murphy notes. "When you watch it, he was charming, he was funny - he joked. And he actually got picked."

So when news spread of Robin's June 20, 1979, disappearance and then murder, Beth had no reason to suspect her boyfriend. They had just spent a weekend together in Northern California.

"There was no difference in personality, no difference in the things we did, the things we talked about," she recalls.

But Beth couldn't account for his whereabouts on June 20.

"As they really focused on Mr. Alcala, they learned that he had no alibi. That nobody could account for his whereabouts at that time," Murphy tells Dow.

And investigators soon learned that Alcala had added to his record.

"Rodney Alcala was on bail for a kidnapping/rape out of Riverside that had just been committed, you know, within a couple of months of the murder of Robin Samsoe," Murphy says. "The more they learned about Rodney Alcala, the more perfectly Rodney Alcala fit into the profile, essentially, of the person that they were looking for."

Rodney Alcala was arrested on July 24, 1979, for the kidnap and murder of Robin Samsoe. But the struggle to prove it had only just begun.

"The name Rodney Alcala. What does that name mean to you today?" Harold Dow asks Robin's mother, Maryanne.

"It means - evil," she replies. "It means horror. It means pain, and a lot of anger."

Robin Samsoe's mother, Maryanne, was convinced Rodney Alcala had murdered her 12-year-old daughter as soon as he was arrested in July 1979. So were Huntington Beach police.

"Every one of those detectives were sure that they had the right guy," says Orange County Asst. D.A. Matt Murphy.

But behind the scenes, investigators were working feverishly to shore up what they knew was a shaky case against Alcala.

"They conduct an interview. They asked him, you know, 'You ever go to the beach and take photos?' And he said, well, from time to time he would do that. And they said, 'Any pictures of people?' And Rodney Alcala kinda looked up and he said, 'Not that I recall,'" says Murphy.

Alcala said he wasn't the curly-haired photographer Bridget had described.

Murphy says, "He essentially told the police that he hadn't been to Huntington Beach since 1974."

Detective Pat Ellis said Huntington Beach Police got an unexpected tip when Alcala's sister came to visit her brother in jail. The conversation was being recorded.

"At one point he mentions him having a storage locker in Seattle, Washington, the cops don't know about," Det. Ellis explains. "He says this. He says, 'It's a good thing they don't know about this. I don't have to tell 'em about it.' He says, 'Do me a favor, get the stuff out of there… get it cleared out.'"

What Alcala didn't know was that police had found a receipt for the locker during a search of his home at the time of his arrest.

"They beat her there and they get inside, and there's the mother lode," says Ellis.

Inside the locker, police found a cache of photos.

"Hundreds, if not thousands, of these different images, and then there are dozens upon dozens of these young women, that, in the pictures, clearly, are in positions of supreme vulnerability," says Murphy.

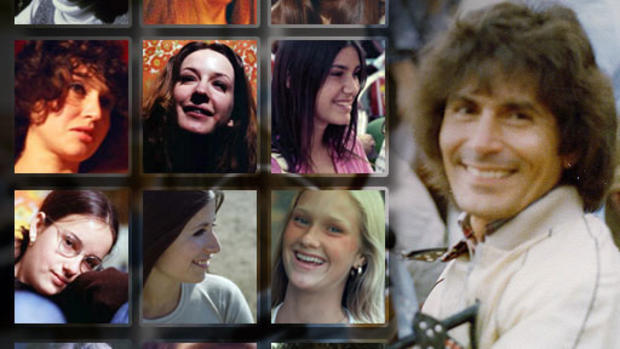

Photos: Help identify images recovered by police

Police learned Alcala had rented the storage facility and moved his belongings there nine days after Robin Samsoe's remains were discovered. So they wondered what he could be hiding. They found no photos of Robin or Bridget. But shots of a young girl rollerskating along a familiar boardwalk caught their eye.

"Those detectives, being in Huntington Beach, actually patrolled that area," says Murphy.

The area was Sunset Beach, near Huntington Beach, the very place Alcala had denied visiting. Police released the photo, hoping someone would come forward.

Lori Werts, the girl in the photos, was 15 years old.

TThis girl, she ran over to my front door and she said, 'Lori, you're on the front page of the paper. They're looking for you," she tells "48 Hours." "My friend Patti and I were at Sunset Beach… we just saw this man with a big camera.

"First he was trying to tell us that he worked for a magazine. And telling us that he was in a contest," she continues. "I thought, 'Well, shoot. I'll be in a magazine. That'll be cool.'"

Lori's friend had marked the date in her diary: June 20.

"And that was the same day… about two miles away from where Robin Samsoe was kidnapped," Murphy says. "So that photograph was of incredible importance."

Two other 16-year-olds said Alcala had approached them on the same day."

"He would approach these teenage girls… And he would use essentially the same line. And then at the end of these encounters, he tried to get them into his car," explains Murphy.

With several independent witnesses identifying Alcala as the photographer on the beach on June 20, police now formed a theory - that Alcala had been out hunting for prey.

So when Alcala ran into Robin Samsoe a second time, he wouldn't be denied.

"Do you think she got in the car willingly?" Harold Dow asks Murphy, as they drive down the street where Robin would have been riding her bike.

Murphy replies, "Robin Samsoe was the one that was… She was only 12, she was innocent, she was naïve, and she was trusting. And she was also very late.

"Just like he promised Tali Shapiro," Murphy continues, "there's no doubt he convinced Robin to get in the car too."

Police were never able to recover Robin's bicycle. And there was still no forensic proof tying Alcala to Robin. Detectives went back to the contents of the storage locker, hoping for more clues.

"Buried under all this stuff was this tiny little silk bag filled with earrings," says Murphy.

Alcala claimed those were his earrings. But when police showed the jewelry to Robin's mother, Maryanne, she recognized a pair of gold ball studs that she said Robin often borrowed.

"How do you think they ended up in Rodney Alcala's possession?" Dow asks Maryanne.

"You mean after he killed my child? After he murdered her? I think he's one of these kind of predators that keep trophies," she replies.

Investigators learned that in the days following Robin's murder, Alcala began to dramatically change his appearance.

"Within 24 hours of the release of that composite, which looks exactly like him, he made arrangements to cut his hair," says Murphy.

"Totally different. The long curly hair was gone," says Huntington Beach Det. Pat Ellis.

Around the same time, Alcala had also changed the carpeting in the back of his car. He told his girlfriend, Beth Kelleher, he was trying to get rid of the smell of spilled gasoline. To investigators, the whole story stunk.

"At that point, those are all the nuts and bolts that you need for a successful prosecution," says Murphy.

In February 1980, nearly one year after Robin Samsoe's murder, Rodney Alcala went on trial.

"Over the course of two-and-a-half months, there were almost 50 witnesses that testified," Murphy recalls. "It was a very long, very difficult case."

The jury convicted Alcala and sentenced him to death.

"It's a poor exchange for my daughter's life," Robin's mother, Maryanne, told reporters following the verdict. "But maybe it'll save somebody else's life by him being gone."

But the relief would be short-lived. In a 5-1 decision, the California State Supreme Court ruled that Rodney Alcala did not receive a fair trial.

The decision would devastate Robin's mother, but the fight for justice was far from over.

After the California Supreme Court overturned Alcala's first conviction in 1984, he was tried and convicted a second time. He was sentenced to death, but once again, the verdict was overturned.

In 2003, the task of putting together the case again fell to Matt Murphy, who, in 1979, was about the same age as Robin Samsoe.

"You are dealing with a guy who made a career out of working the system. Two trials, two convictions, twice sentenced to death, twice overturned. How do you prepare for a case like this?" Harold Dow asks Murphy.

"When they reversed it, they also removed a substantial amount of evidence," Murphy replies. "So when it wound up on my desk, we had to basically start from ground zero and work our way up."

Murphy would soon get a huge break. During theyears the Samsoe case had wandered through the appellate courts, DNA technology had caught up with Rodney Alcala. Now, Los Angeles cold case squads suddenly linked him to three other unsolved murders.

"The DNA technology was very strong as it pointed to one person and one person only, and that was Rodney Alcala," says Los Angeles County Deputy D.A. Gina Satriano.

Satriano charged Alcala for the murders of 18-year-old Jill Barcomb, 27-year-old Georgia Wixted, and 32-year-old Charlotte Lamb, who all had been killed between November 1977 and June 1978.

"Right at that moment," Murphy says, "we realized that not only is Rodney Alcala a vicious murderer in our case, but, in fact, he is the serial killer that we always suspected him to be."

There was also evidence linking Alcala to yet another Los Angeles murder: 21-year-old Jill Parenteau who had been killed just six days before Robin Samsoe disappeared.

"Jill Parenteau's case was tied to Rodney Alcala back in '79," Satriano explains.

Prosecutors had dropped the case at the time because they felt it was too weak. Authorities now saw that it fit the pattern of the other murders.

"In addition to the sexual assault and the fact that they were all left naked and posed, and to the beatings and traumas to the head, each of these women were strangled with ligatures, with some sort of tie around their neck."

"Rodney Alcala was committing murders all over the place in an effort to work the system. In an effort to confuse law enforcement," says Murphy.

"In different jurisdictions?" Harold Dow asks. "Hoping that the law enforcement would never talk to each other?"

"That's right," Murphy says, "and for years, they didn't."

Believing they had enough evidence to convict Rodney Alcala as a serial killer, Matt Murphy and Gina Satriano wanted to prosecute the five Los Angeles-area murders together.

"Having them together really paints the true picture of who Rodney Alcala is and gives the jury a realistic vision of how he commits his crimes," says Satriano.

Two California counties had never shared a murder case and Alcala successfully fought off the joint trial for years. The California State Supreme Court ultimately ruled for the prosecution. In January 2010, almost 31 years after Robin Samsoe's murder, Rodney Alcala went on trial again.

The Samsoes are now joined by four other families for whom the pain of loss is still as raw as it was 30 years ago.

"One of the many things that hurts me is that that was the last face she saw. And that bothers me 'cuz he's so ugly and so evil," says Dedee Parenteau, Jill's sister.

"For so many years, I just felt like I was always looking over my shoulder," Georgia Wixted's sister, Ann Michelena, says. "There was somebody out there that had murdered my sister. And where was he? And was he coming back?"

"Your heart goes out to 'em," Rob Samsoe says. "We've had somebody to hate for 31 years. They haven't."

Matt Murphy knows getting a conviction won't be enough.

"We've got to get it - not only a conviction, but we gotta get a conviction that's gonna be upheld on appeal," he tells Dow.

Complicating the legal challenge for prosecutors is that Rodney Alcala is serving as his own attorney.

Even though he stands accused of five vicious murders, as Alcala addresses the court, it is clear that for him, the Robin Samsoe case stands apart.

"He knew the facts cold," Murphy says. "And he'd spent 30 years on death row memorizing every single photograph, every single police report, every single detail of the case."

Alcala had even written a book about the Samsoe case. He is so eager to defend himself, he takes the stand.

"By taking the stand, it allowed the door to be opened to so many things," says Murphy, who could now attack Alcala using statements he made in his book.

"It was published in 1994, long before these DNA tests were conducted," Murphy continues. "So he was married to a certain set of facts."

Like the facts surrounding the trophy bag of earrings found in Alcala's storage shed.

Alcala had disputed the evidence that one pair had been worn by Robin Samsoe. But because of new DNA evidence, he could not dispute that another pair belonged to one of his other victims: Charlotte Lamb.

"In his book, he said that his sister Christine gave him those earrings," Murphy says. "Twenty-seven years later, we were able to test those earrings and we got a DNA hit for Charlotte Lamb."

Undaunted, Alcala calls Robin's mother, Maryanne, as a defense witness.

"That was one of the hardest things I've ever had to do in my life," she tells Dow. "Having him ask me questions."

Desperate to impeach Maryanne's character, Alcala confronts her about her testimony at his first trial, when she reportedly brought a gun to court.

"He asked if you brought a gun to court during the first trial… And you answered?" Harold Dow asks Maryanne.

'Yes, I did," she says.

"Were you gonna shoot him?"

"I was gonna shoot him right between the eyes if I could've gotten a shot at him."

"What stopped you?"

"Robin's hand on my wrist if the truth be known," she says. "All the sudden I smelled her shampoo, and I felt this warmth on my hand. And I couldn't get my hand out of my purse."

An even bigger miscalculation for Alcala was ignoring the Los Angeles cases.

"That was bizarre… It was as if those victims were invisible to him," Satriano says. "The scientific evidence in the L.A. cases totally overwhelmed him, was over his head, and he had no idea how to challenge it."

"The four Los Angeles cases, is a device for secretly and dishonestly attempting to control the outcome of the unrelated Samsoe case," Alcala tells the court in his closing. "Magical thinking…"

In his own closing argument, Matt Murphy ends on what is for him, too, the heart of the trial.

"Part of what gets that guy off over there - it's not just the conquest and the sneakin' around and the rape and the killing and the torture and the sadistic infliction of pain. He wants a free murder," Murphy tells the court. "You're gonna convict him of the L.A. cases. He knows that. Everybody knows that. But Robin Samsoe's day in court is today."

It's a familiar feeling for Robin Samsoe's family, as they wait for the third jury - over a period of 30 years - to decide Rodney Alcala's fate.

"Your stomach's in a knot. It's up in your throat," Rob Samsoe says. "You're like a zombie walkin' around."

The jury takes just one day to find Alcala guilty of Robin Samsoe's murder. He's also found guilty of murdering the four other women - Jill Parenteau, Jill Barcomb, Georgia Wixted and Charlotte Lamb.

"Rodney Alcala does absolutely 100 percent deserve to die for what he did," Orange County Asst. D.A. Matt Murphy says.

In a separate penalty phase, to ensure that Alcala gets the ultimate punishment, the prosecution called a ghost from his past to the stand.

"My name is Tali Shapiro. I'm alive because I have a guardian angel."

Tali Shapiro, kidnapped and left for dead in 1968, was not prepared for what Rodney Alcala said to her.

"He apologized," she says. "And I couldn't even tell you what it was exactly he said, because I didn't hear him."

Shapiro, who has a teenage son and works as a personal chef, insists she's not a victim. But she wants the system that set her attacker free held accountable.

"It should have stopped with me," she says. "And why - why in the world are there so many other victims when it was a known fact of what he did to me?"

After Tali Shapiro's dramatic appearance, the jury was finally ready to recommend a sentence for Rodney Alcala.

Alcala, addressing the same jury that had convicted him of murder, makes an awkward argument for clemency:

"Let me put the death penalty in perspective for you," he says. "If you desire to join in the killing of a human being, you and the families of the victims will have to wait at least 15 to 20 years while the case slowly churns through the appellate process."

"He wanted to play an Arlo Guthrie song, "Alice's Restaurant," and there's a part in that song where he talks about wanting to kill people," Murphy says. "And he played that, incredibly, for the jury."

Jurors heard the following play in court: "I wanna kill, I wanna kill, I wanna see blood and gore and guts and veins in my teeth. Eat dead burnt bodies. I mean, kill, kill, kill, kill."

"Matt Murphy said that that song told you more about Rodney Alcala than anything else that he did in that courtroom. That song was him," Harold Dow remarks to Tim Samsoe.

"I pictured him singin' the lyrics when it was on," says Tim.

Alcala's perverse closing statements did not sway the jury. They took only an afternoon to decide to sentence him to death.

But the saga of Rodney Alcala's murderous odyssey still hasn't ended. After he was convicted, Huntington Beach police released photos recovered from Alcala's Seattle storage locker of more than 100 young women, and even some children. Investigators are hoping to identify them, and learn if Alcala claimed still more victims.

"We just don't know.That's what's frustrating, not knowing who's alive and who's not," Huntington Beach Police Det. Pat Ellis says while looking at the photos.

"Maybe, just maybe, there's another victim out there, or victims someplace across the United States or possibly out of the United States," he says.

The nationwide interest in the trial and the photos have given new life to murder cases that have remained dormant for years.

"There are four other murders in New York that have been linked to Rodney Alcala," Murphy says. "We've worked very closely with the police in New York. And we have every confidence that they will get the job done."

"I don't want him to go to no other state and be held accountable for no other - nothing else, because he can only be killed once," Robin's mother, Maryanne, tells Harold Dow. "I want him to die here."

"I want it carried out," Maryanne says. "I wanna live one day longer than him. I wanna live one day without feeling or hearing the name Rodney Alcala in my mind. I could die a happy woman."