3D printing helps doctors safely deliver baby

When Megan Thompson was just over 30 weeks pregnant with her son Conan, doctors noticed a large mass on his face during an ultrasound that they couldn't identify.

Fearing the mass may be cancerous, doctors didn't know if it would block the baby's airways and whether they would need to perform a set of complex procedures in order for him to be able to breathe during delivery.

"It was really traumatizing," Thompson, 22, told CBS News. "I got into a state where I was completely numb because I didn't know if he was going to be alive or dead when he came out."

If the airways were blocked, the doctors would need to perform an exit procedure -- a riskier form of a cesarean section in which the mother is under anesthesia and the baby remains attached to the placenta by the umbilical cord until an airway can be established to allow the baby to breathe. "The thought of that was so scary," Thompson said.

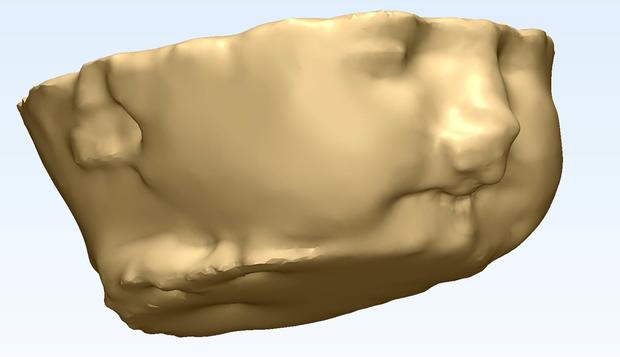

She was given more tests, but just how dangerous the mass might be still wasn't clear to her doctors at C.S. Mott Children's Hospital at the University of Michigan Health System. They then decided to use a specialized MRI that captured more data in order to build a model of the fetus's face with a 3D printer.

The 3D model predicted a cleft lip and a cleft palate without airway obstruction. Thompson was able to deliver her son safely.

"By doing the 3D modeling, we were able to tell that the mass wasn't cancerous and determined that it would be safe to not do the most advanced types of intervention," Dr. Glenn Green, Associate Professor of Pediatric Otolaryngology at Mott Children's, told CBS News.

"When I heard him screaming and crying for the first time, I cried tears of joy because I knew he was OK and could breathe," Thompson said.

Green presented the case study in a paper published this week in the journal Pediatrics.

This was the first time 3D printing technology has been used in utero. Green says the technology has huge implications for the future.

When it comes to possible airway obstruction in fetuses, "a lot of times there's just not enough time to act and a lot of babies end up dying when they're born, unfortunately," Green said. "If there is a lot of time then you can get ultrasounds and various scans to try to figure out what it is and plan an intervention."

In Thompson's case, though, there wasn't a lot of time to figure out what was wrong. But the 3D printing technology allowed the doctors to make decisions within 24 hours.

"We'd like to be able to speed it up from there so that when something happens, we can figure it out maybe even while a woman is going through contractions," Green said.

Dr. Albert Woo, a pediatric plastic surgeon at St. Louis Children's Hospital, told HealthDay that the use of 3D printing "in this specific instance where airway distress is a major possible issue, potentially can help to revolutionize that field. It really provides a new tool so that doctors are much better prepared to deal with airway problems or other congenital anomalies that they need to diagnose critically right when babies are born." Woo was not involved in the study.

Working with 3D models, Green points out, allows doctors to do things they would otherwise not be able to.

"You can hold the baby in your hand before you see them and get an exact feel for what they're like. You can discuss with other doctors and specialists and make plans while looking at exactly what we're going to be doing. You can test instruments to make sure that they're the right size," he said. "And not only can you make a 1 to 1 model, but you can make a 10 to 1 model, make something 10 times its size, to get a really detailed view of what's going on."

Down the road, Green suggests that 3D printing could be used to help many more doctors and parents during pregnancies. "We think this is a real game changer," Green said. "We see this as OB's could potentially have a 3D printer right by the ultrasound machine."

While the technology isn't cheap, the cost of 3D printing is steadily declining and Green believes it will soon become more accessible to a greater number of hospitals. "The first printer in our laboratory cost over $100,000. The last one that we bought was about $1,000," he said. "The capabilities are different but in a very real way the costs have dropped."

Thompson said she had seen stories in the news about 3D printing assisting doctors with heart surgeries but didn't know it was possible to use it for fetuses. She said she is grateful her doctors were able to use the technology to help deliver her son.

Conan is now a happy 9-month-old boy. "He's healthy and growing big," Thompson said. He had cleft-lip surgery in June and will be undergoing a procedure to correct his cleft palate in November.