What Happened At Minnesota's 21 Native-American Boarding Schools? Unpacking A Complex History

Originally published May 20, 2022

RED WING, Minn. (WCCO) – A trip to the Goodhue County Historical Society's basement in Red Wing is a trip back to a complex and complicated time in United States history. And right now, the traveling display the organization spent years trying to secure is once again a topic of national conversation.

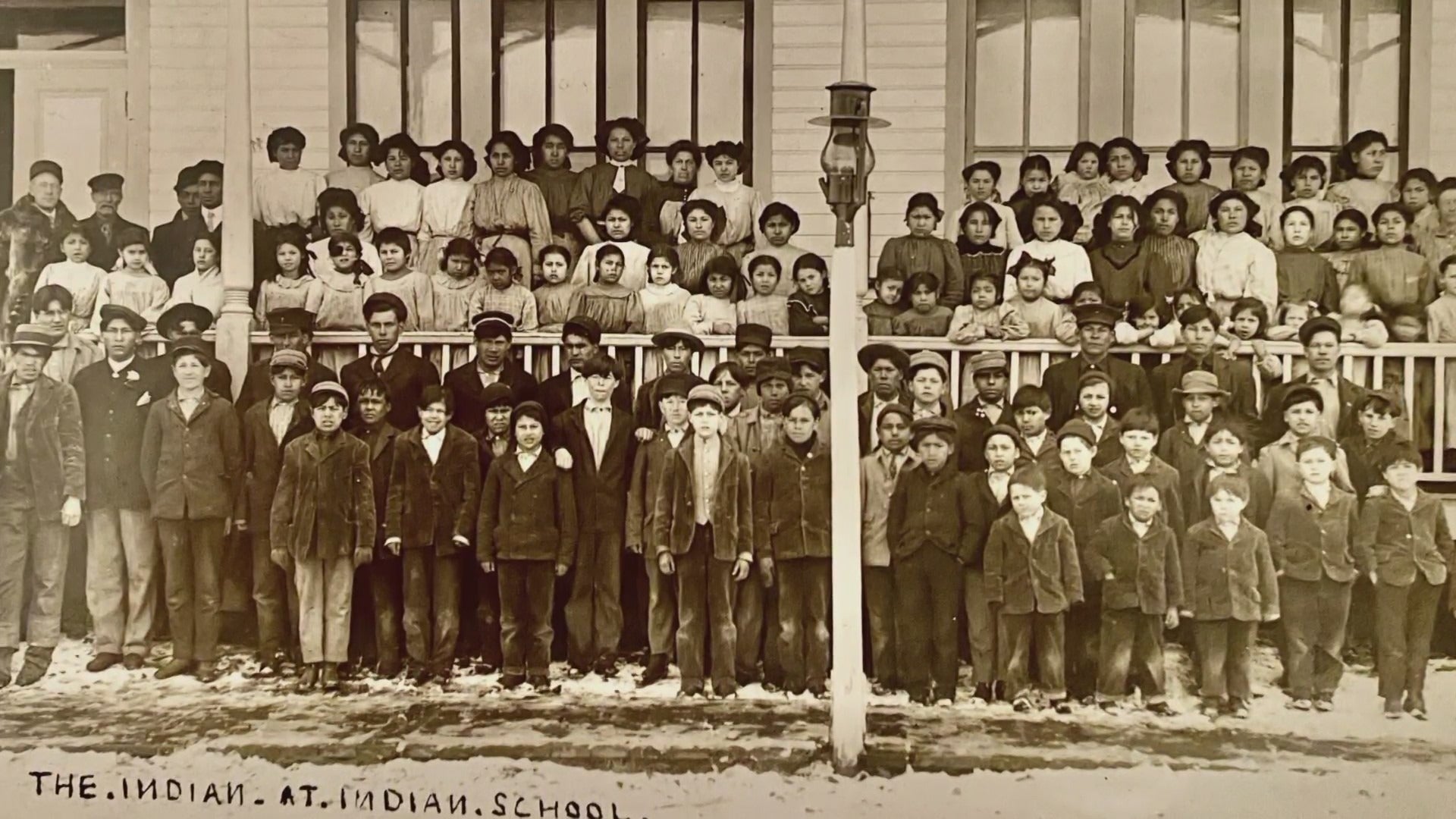

Titled "Away From Home: American Indian Boarding School Stories," the display on loan from Arizona's Heard Museum details the decades Native American children spent in federally run boarding schools across the country through artifacts and first-person testimony.

"This is definitely a conversation that needs to be had," said Collections Curator Afton Esson. "It's one of those topics that's powerful and emotional and having it right now is the perfect time to share this topic with the community."

The perfect time, perhaps, because for the first time ever the United States is attempting to extensively document exactly what happened at the schools scattered around the country. The Department of Interior launched the effort in 2021, shortly after a closer look into similar schools in Canada revealed a massive number of unmarked graves at multiple locations.

A Complicated History

University of Minnesota Professor Brenda Child has long been fascinated by the concept of Native American Boarding Schools. A Red Lake Citizen herself, Child says some of her earliest memories involve listening to her grandmother's stories of attending Flandreau Indian School north of Sioux Falls.

"She's the first person who told me about boarding school – I could hear her voice," Child said. "She told me she had worked as a domestic servant for the local white households, and that this is what the Indian girls did."

Schools like Flandreau began opening across the country towards the end of the 1800s, Child said. Initially, they were a home for children whose parents were prisoners of war in the ongoing battles between Native Americans and colonizers of the time.

As the United States Government worked to move Native Americans into reservation areas, the schools boomed in numbers. At their peak, Child says one in three native children were being sent to an off-reservation boarding school. There, not only would they have no contact with their families, but they'd also be made to cut their hair, speak English, learn Christianity, and remove themselves from tribal customs. This was an act of forced assimilation, Child said.

"The idea was that they wouldn't really need a homeland anymore. They could go out into American society and live like everybody else," she said.

At the same time, Native Americans had their land taken from them at a rate faster than ever before, Child said. This period of dispossession, highlighted in Minnesota by the Nelson Act of 1889, took more than 90% of native land away from tribes throughout the state.

"Boarding schools in a sense did not benefit American Indians. It was a twin policy that went along with dispossession that left American Indians in the 1930s poorer than they'd ever been before."

A Deadly Stay

Conditions at schools across the country ranged from cramped and crowded to negligence. This meant diseases of the time, Tuberculosis and an influenza epidemic, could ravage through the dormitories in classroom at record pace. To this day, it's unknown how many students died at boarding schools during this time.

The Department of Interior's second phase of its Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative seeks to answer this question.

Child says in addition to disease, it's likely students were beaten through a system of corporal punishment.

"If you ran away from boarding school or you were really rebellious one way or another, you could go to jail on campus, and they had buildings where they sometimes locked students up for punishment."

Understanding An Impact

Professor Child says unlike many, her grandmother and great-grandfather were not punished for speaking their native language.

In fact, Child's book, "Boarding School Seasons," details hundreds of firsthand accounts through letters and other records of students who not only attended the schools, but recommended friends attend also.

Still, she says the impact of the schools is apparent – and takes understand the assimilation era and Native American dispossession to gain the full context. Reparations, she says, should focus first on returning land to the tribes it was taken from.

"The idea of the boarding schools during that era was to separate Indian children from their families and communities," she said. "The idea was to kind of get people away from Minnesota."

"Away From Home" will be on display at the Goodhue County Historical Society until May 25. It is a no-cost exhibit.