How the Twin Cities Hmong community is working to address alarming trend of youth deaths by suicide

ST. PAUL, Minn. — May is Mental Health Awareness month, but it's also Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

The two have collided in recent years as many Asian communities have been forced to set aside the stigma to address a growing problem.

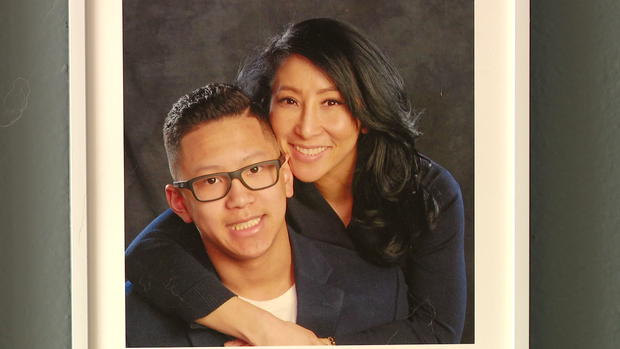

In the Hmong community, suicide deaths among youth — especially boys — are alarming. Kou Xiong and Mee Yang know the pain all too well after their son Max died by suicide in 2021.

"It never gets any easier," Xiong said. "It never gets any easier."

Xiong said every day is all about not giving up hope.

"Every day I still have to tell myself not today," he said. "Not today."

Yang said it's just as tough for her in Woodbury.

"I'm going to live with his lost forever," she said.

Both Xiong and Yang said they are still brokenhearted and long for the simplest things.

"Him calling me dad," Xiong said when asked what he missed most about his son.

"I miss everything," Yang said. "I miss him coming to me and giving me hugs."

Both said they wished Max was still here.

"It's something you don't see coming," Xiong said.

This June 17 will mark three years since Max died by suicide. He was just 17 years old.

"A parent's worst nightmare," Xiong said. "Stuff that you are afraid to even fathom and think."

Three years later, Xiong still visit's Max's room every day.

"I still tell him good morning," he said. "I still tell him goodnight before I go to bed. This is how he left it and it's still like this."

And Yang is still brought to tears with reminders everywhere of Max.

"I really wish he would have known how special he was," Yang said. "I don't think he did."

Both parents are still left wondering what they might have missed.

"I never read an outburst from him saying, 'Oh, I hate my life. I'd rather not be here,''' Xiong said. "Nothing like that whatsoever."

"He was sleeping often," Yang remembered about the time shortly before Max died. "He had lost his motivation for all the things that he loved, but I just kind of brushed it off and just took it as, 'OK, this is the teenage years, this is normal for a teenager.'"

His parents say Max was kind, caring and smart. He was surrounded by a great group of friends and was a member of the robotics team at North High School. He was a member of the ROTC and was planning on joining the military after graduation.

"We weren't just father and son," Xiong said. "We had started becoming friends [and] training partners, because we would box, wrestle."

Xiong and Yang said they now want to help other Hmong families change the narrative.

"It's too late for me," Yang said through tears. "But it may not be too late for whoever is out there."

"There's been an influx of Hmong families and children seeking out support within the community," said Mary Her, clinical social worker and co-chair of Project Tshav Ntuj.

Mary Her, Yee Xiong, Dani Thao and Tsua Xiong all work in the mental health profession in Minnesota. Minnesota doesn't have specific numbers on suicide deaths in the Hmong community, but through their work, they said the number of Hmong youth dying by suicide is alarming.

"Hmong American youths are four to five times more likely to have suicidal thoughts compared to other youths," said Yee Xiong, who also co-chairs Project Tshav Ntuj and is a practicing psychiatrist.

They along with more than a dozen other professionals were a part of the grassroots effort to launch Project Tshav Ntuj five years ago. The name translates to Project Sunshine. The goal is to serve as a beacon of hope in the community by connecting people with resources and providing safe spaces and opportunities for families to talk about mental health.

"In a lot of Asian communities, mental illness is something you don't talk about in the home," said Her.

They added the cultural pressures are also met with language barriers.

"We don't have words for bipolar disorder," said Thao, a board member for Project Tshav Ntuj and a therapy graduate student. "I guess we don't really have words for anxiety so we don't have words that directly translate."

Tsua Xiong, a mental health practitioner and board member for project Tshav Ntuj, also said the pressures can be different for Hmong boys than girls.

"Being a good husband or a good male figure in the community," he said. "It could be like boys trying to make their fathers proud so they put the extra pressures on themselves."

They said while the conversations in the Hmong community have shifted, there's still more work that needs to be done.

"There's so many resources out there," said Yang. "Talk to your children. talk to your loved ones. Listen to your intuitions."

"The only mistake that I felt I made what that I felt that it couldn't happen to me," said Kou Xiong.

Kou Xiong and Yang said the important conversations could help save a life worth living.

"I really hope his story can help others," said Yang of her son. "I really do."

If you or someone you know is in emotional distress, get help from the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline by calling or texting 988. Trained crisis counselors are available 24 hours a day to talk about anything.In addition, help is available from the National Alliance on Mental Illness, or NAMI. Call the NAMI Helpline at 800-950-6264 or text "HelpLine" to 62640. There are more than 600 local NAMI organizations and affiliates across the country, many of which offer free support and education programs.