How do you know when to seek mental health help for your child?

MINNEAPOLIS -- There are cries for help like never before from Minnesota's youth, as 29% of students say they've experienced depression, anxiety, and other mental health struggles for six months or more. That's more than ever before recorded by the state.

This week, we are exploring solutions across our community. WCCO's Susan Elizabeth-Littlefield visited Children's Minnesota to ask how to know if your child needs help.

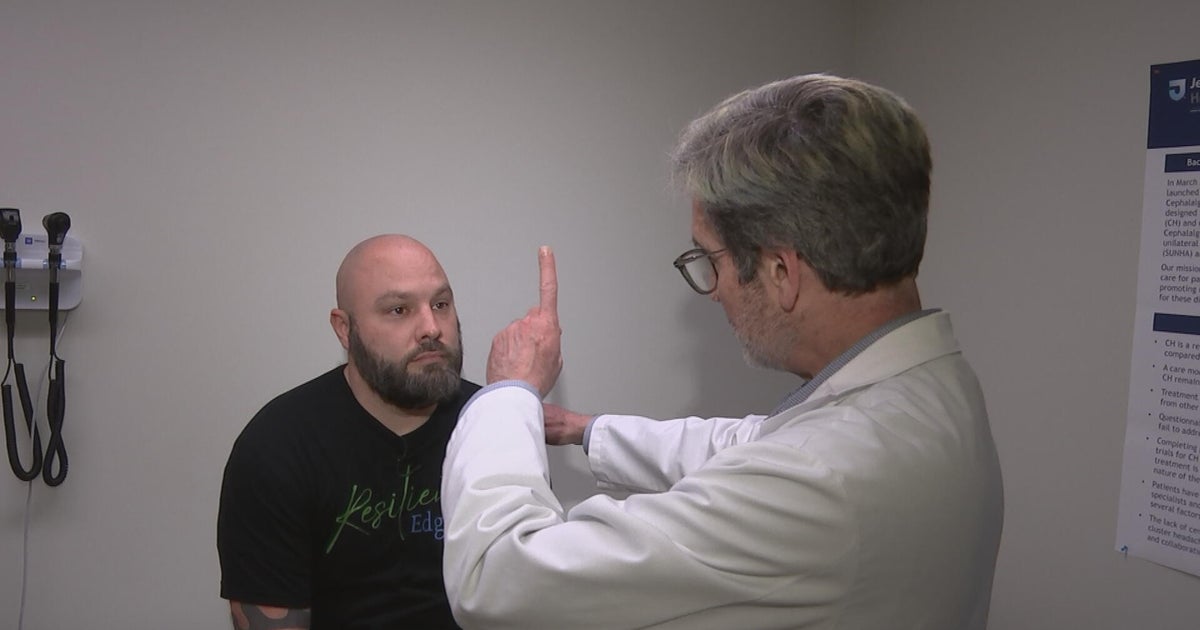

Countering a potentially scary experience with careful planning, every detail of the new inpatient unit at Children's Minnesota in St. Paul has young people in mind.

"I wanted it to feel warm and inviting," director Jamie Winter said. "Two sleep surfaces, one for a child and another for a parent or guardian to be able to spend the night. ... We wanted to be able to give kids some control and autonomy over their space."

Winter says over the last decade, they've seen an increase in demand that's spiked over the last couple years, when they saw a 30% increase in hospitalizations.

"Where I'm seeing a pretty dramatic increase is the suicidal ideation and worsening depression and anxiety," Winter said.

The inpatient unit is designed specifically for people 18 and under. The unit opened in November.

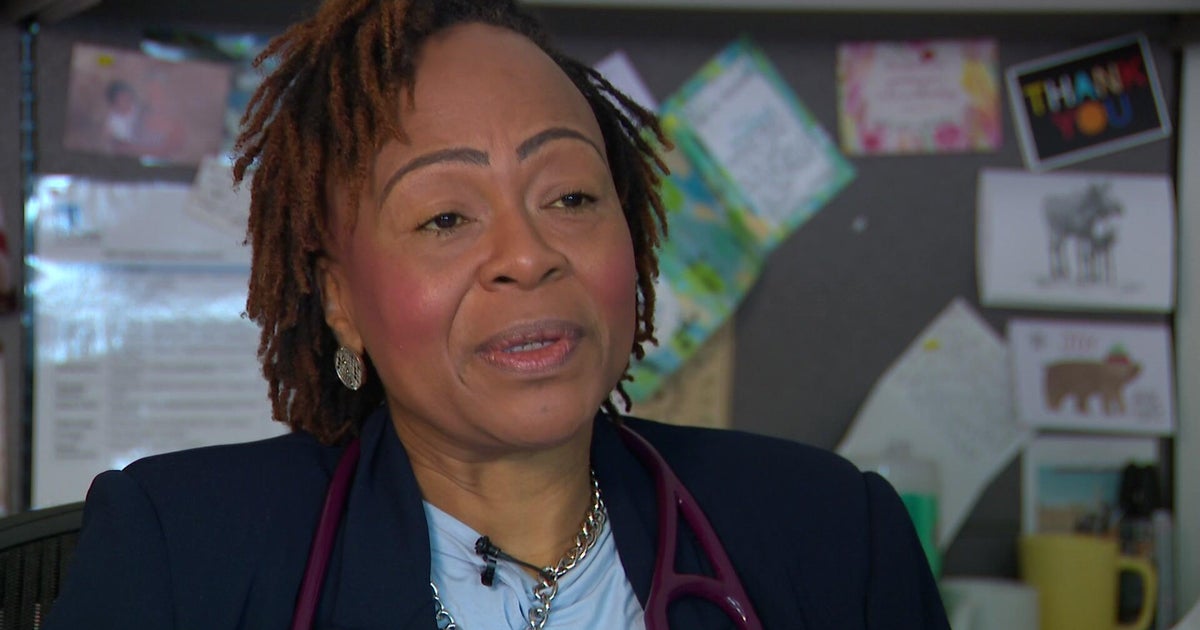

"If they are feeling things like hopeless or if they are having suicidal thoughts -- which are a lot more common than people think and are treatable -- or if they are feeling more down or depressed ideally they share it with their parent," Jessica Brisbois, manager of acute mental health services at Children's. "And that's when the parent can say 'OK, let's look into getting you a therapist.'"

Some warning signs are sudden changes in behavior like a drop in school performance, avoiding school altogether, if they're not hanging out with friends, or if they suddenly lose interest in their normal activities.

When is it time to go to the ER?

"If the child's identifying that they aren't feeling safe to that point where they have a plan that they're going to hurt themselves, and they have an intent to act on the plan or if they're not sure whether they can keep themselves from acting on it," Brisbois said.

Both doctors say the goal of the ER is to stabilize children and work with families to make a plan.

"Hearing that your child is having thoughts of ending their own life, that's really scary. So we try to walk along side those families," Winter said.

Four months after opening the inpatient unit, they're seeing the impact.

"We actually had feedback from a parent that I just had the opportunity to read that said, 'Thank you, you've saved our child's life,'" Winter said.

Help is available 24 hours a day by calling 988 for the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. Click here for other youth mental health resources.