How Do Vaccines Become Required For Minnesota Schoolchildren?

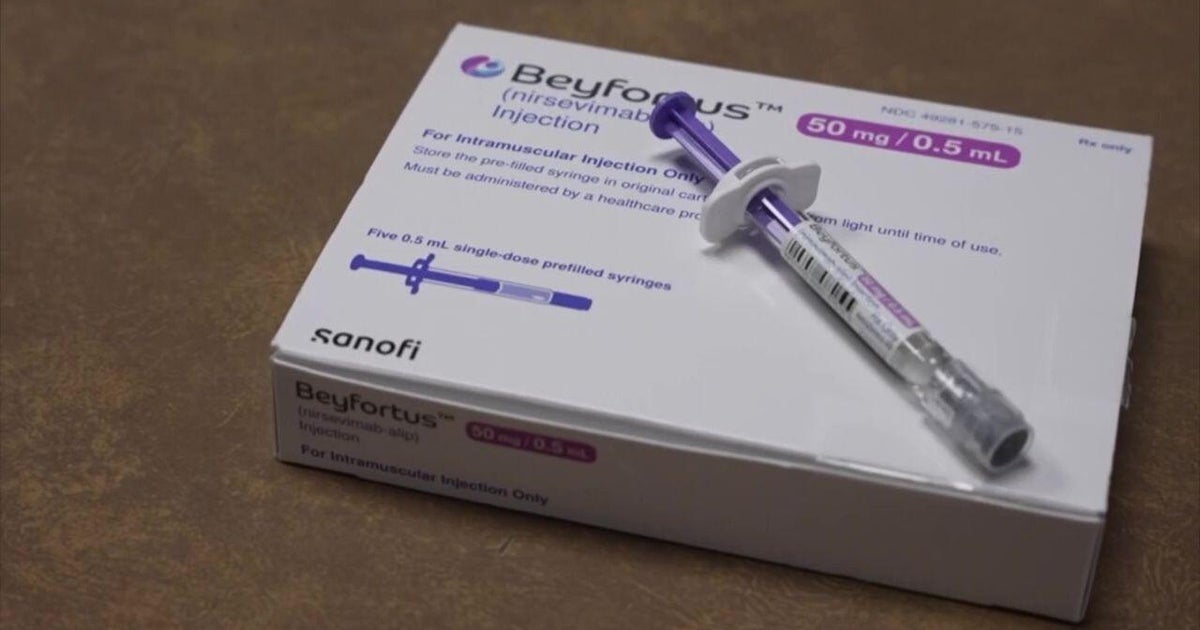

MINNEAPOLIS (WCCO) - This week, Pfizer submitted its data on 5 to 11 year olds about the COVID-19 vaccine. It's another step toward making the shot available to younger children.

While the COVID-19 shots are a new vaccine, other vaccinations are nothing new to Minnesota students. Already they're required to get several other shots to enter kindergarten, including DTap, polio, MMR, Hepatitis B and Chickenpox. In seventh grade, students are required to receive the meningococcal vaccine.

Some exemptions are allowed for medical and non-medical reasons, but approximately 90% of Minnesota schoolchildren have these shots.

So, how does a vaccine become part of Minnesota childcare and school immunization law? Good Question.

School vaccination laws date back the 1850s when Massachusetts wanted to prevent smallpox. It wasn't until the 1960s in Minnesota that the vaccine requirements for children were put into law. Back then, changes to the vaccine law had to be approved by the state legislature. In 1967, it approved measles. In 1973, it approved rubella. In 1978, it approved mumps, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and polio.

But by the time Minnesota added the varicella (chickenpox) vaccine in 2003, the law had changed to also allow the Minnesota Department of Health rule-making authority to create policy to carry out the state's law.

It's a process than can take 12-18 months.

"We start by publishing a notice that we're going to pursue rule-making on a particular issue," said Kris Ehresmann, MDH Director of Infectious Diseases. "Then there's a back-and-forth process where we say what we're going to do and people can provide input."

In general, the state will hold an administrative law hearing in front of a judge. MDH must also prepare a statement that lays out why it believes the change is in accordance with the "necessary and reasonable standard."

"We look at the epidemiology of the disease, the morbidity and mortality rates from the disease, the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, costs. You know, there's a range of things that we look at," Ehresmann said.

MDH also looks at whether the vaccine is licensed, recommended by the CDC and its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, and if school is a primary route of transmission.

Ehresmann says a vaccine like influenza is different from the other required vaccines because most of those infer lifelong immunity, while influenza is required annually.

"That's a huge implementation burden, so that's one of the things that we consider as well," she said.

Legislative leaders told WCCO that there are no current plans to address requiring the COVID-19 vaccine for Minnesota students. As for whether MDH might consider it in two to three years, Ehresmann said the illness from the virus is significant enough that it would be something they would evaluate.

Until then, though, Ehresmann warns parents they shouldn't wait until a vaccine is required before considering it for their children.

"While I really value the process that we need to go through to get something through the law, I don't want parents to think they need to wait for that," she said. "Take advantage of the vaccines as soon as they become available so they can get protected and stay in school."