"I was so happy I didn't even know what to do": Group helps free innocent people from prison

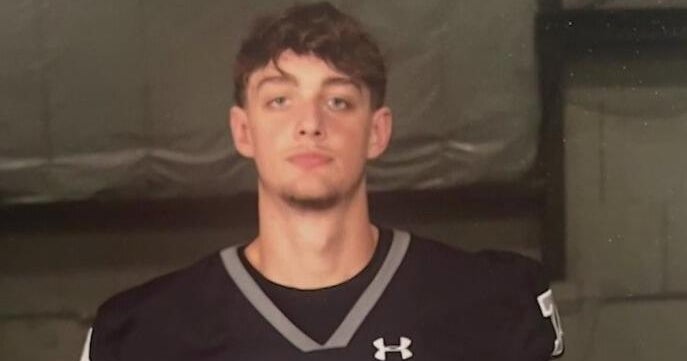

MINNEAPOLIS -- April 12, 2014, was a normal night out for Javon Davis. But soon after, police were looking for him -- he was arrested.

"And I'm like, 'what are they looking for me for? And they were like, 'I don't know, they won't tell us, some assault.' So I'm like, 'assault, I ain't assaulted nobody," Javon said. "I'm asking them, 'what am I under arrest for? Why y'all arresting me?' And one of the cops looked back and said something funny like, 'oh you know who you shot.' I'm like -- who I shot? I ain't shoot nobody."

Javon was accused of shooting two people coming out of Target Field.

"I wasn't nowhere near there," Javon said. "At the time of the shooting, no not at all."

First, he waited.

"I sat in the county for a year waiting to go to trial," Javon said. "[I was thinking] 'why would God put me in this situation?'"

Then, he was convicted to 33 years in prison.

"I didn't make peace with it, I was just the angriest person in the world," Javon said. "It's a lot of dark spots down there."

Darkness and then a spark of hope -- two student lawyers from the Great Northern Innocence Project visited him in prison.

Javon wrote a letter to them, pleading his case.

"I remember writing on the paper, if anyone is Innocence Project innocent, I'm Innocence Project innocent," Javon said.

The team agreed but warned Javon it might not work. Lawyers told him overturning convictions -- even if someone is innocent -- is nearly impossible. But they did it.

After nearly six years in prison, Javon walked free.

"I was so happy I didn't even know what to do, I just sat there," Javon said.

The team successfully proved Javon's trial attorney was ineffective -- a rare victory for a team that reviews hundreds of requests for help every year.

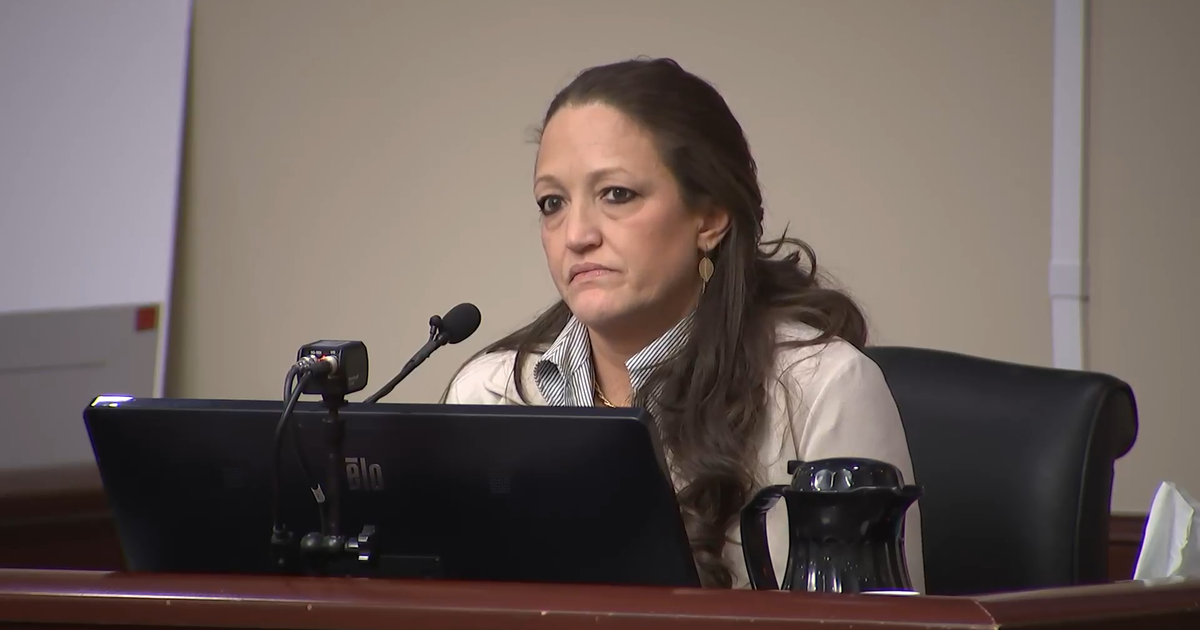

"Anywhere from 2-8% of people who are convicted of crimes are likely to be innocent," said Sara Jones, Executive Director of the Innocence Project. "Let's say there's 9,000 people in prison -- 5% would be 450 people."

Jones says several things went wrong for Javon.

"It was witnesses lying, supposed informants saying Javon did it when they didn't and getting some sort of deal for saying that," Jones said. "And Javon had an alibi, he was on the phone. He was calling and texting and there was never an attempt to find the text messages, the records of those, and so forth."

Jones says cracks in our system also played a part. The group has helped change laws to improve the use of eyewitness identifications and to track flaws with jailhouse informants. And they'll continue to work for people like Javon.

"I like to think we get it right more often than not, but when we get it wrong, like the worst kind of wrong, is what happened to Javon," Jones said.

"It means so much to me because people don't believe you, especially where I come from, it's hard to put your neck out there for somebody that you don't know and develop trust and love for them and they did that," Javon said.

Javon is still seeking compensation from the state.

The same team helped bring Thomas Rhodes home after 25 years in prison. That was the first result that came from the state's Conviction Review Unit -- something that this group helped start with federal funding and a partnership with the Attorney General's Office.

But they're not just taking on individual cases, they're doing advocacy work to hopefully make our system more just in general.

Since its inception in 2001, the Great North Innocence Project has helped free 10 people who were in prison for crimes they did not commit. Those men spent a combined 113 years behind bars.