Good Question: How Does Doctor-Assisted Suicide Work?

MINNEAPOLIS (WCCO) – A 29-year-old woman with terminal brain cancer has decided to end her own life on Nov. 1, two days after her husband's birthday.

Brittany Maynard's doctors told her she only has months to live and that her natural death would be very painful.

So, she and her family moved to Oregon, one of four states that allow for physician aid-in-dying, or physician assisted suicide.

"I can't even tell you the amount of relief that I know that I don't have to die in a way that's been described to me, the way brain cancer would take me on my own," she said in a video about her journey produced by Compassion & Choices.

Maynard already has the pills stored in a safe spot and says she plan to take them on her own on Nov. 1.

To get those pills, she first had to move to Oregon and establish residency.

Then, she had to make an oral request to her doctor, wait 15 days and make another oral request.

A required written request followed and had to be witnessed by two people, one of whom was unrelated.

Two doctors had to say Maynard had less than six months to live and that she was able to make this decision on her own.

The law requires she administer the pills herself because it would be considered euthanasia if a doctor were to inject her with a lethal dose of painkillers.

Despite being legal in some European countries, euthanasia is not legal anywhere in the United States.

Four states in the country have laws like these.

Oregon was the first state to have Death with Dignity Act.

Voters approved of the law in 1994 and it went into effect in 1997.

In 2008, voters in Washington state voted to pass its own Death with Dignity law.

In 2009, the Montana Supreme Court ruled doctors could assist patients by ending their lives.

In 2013, the Vermont General Assembly passed the state's Patient Choice and Control at End of Life Act.

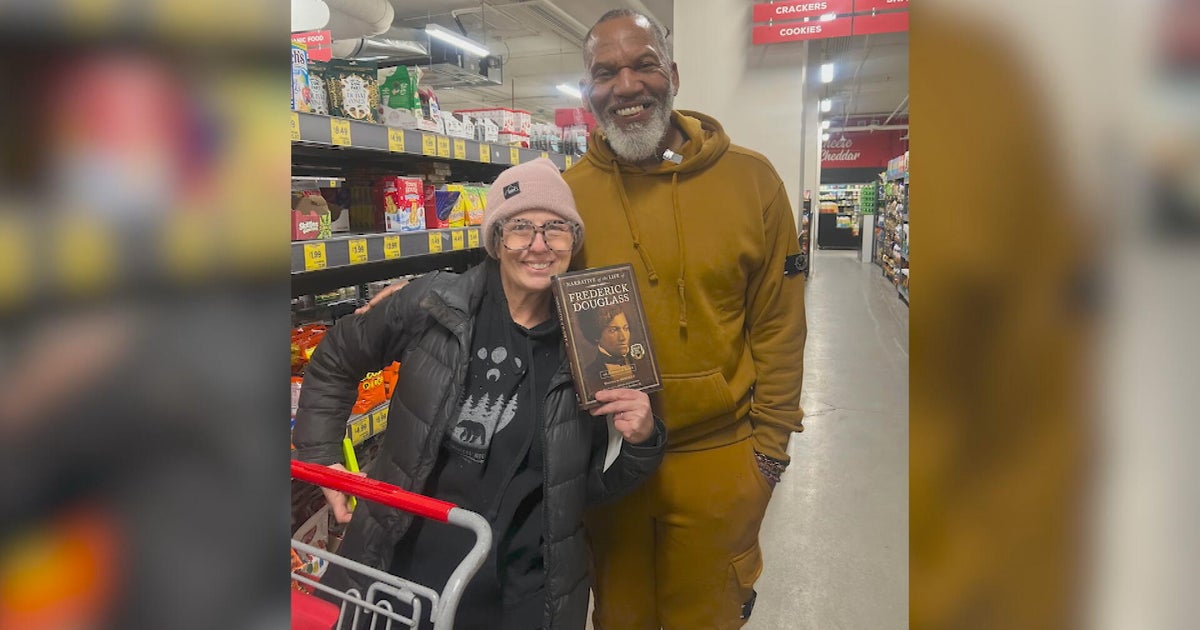

Dr. Vic Sandler is the medical director for Fairview Home Care & Hospice. He's cared for hundreds of dying patients.

"The patients or the family will say, 'Can't you give them something that will help them die or to make their dying process more rapid and end their suffering,'" he said. "I tell them, very clearly, n Minnesota, we can't do that. We can't provide them something with the purpose of ending someone's life."

In Minnesota, Dr. Sandler says Minnesota follows the precedent set by the U.S. Supreme Court that allows physicians to do everything in their power to ease a patient's suffering.

He has used palliative sedation, a rarely-used procedure that can relieve suffering in those people who can't get comfortable any other way.

"Even if it expedites their dying process, as long as the purpose and the goal of the treatment is to relieve suffering, then it's ok. It's legal," he said.

In 2013, doctors wrote lethal prescriptions for 122 people. Only 71 used them, or 0.2 percent of all Oregon deaths that year.

"People receive this prescription and that, in many ways, empowers them," Sandler said. "What often happens is that people when they receive this prescription, often in fact, don't use it. But avail themselves of palliative care treatments."