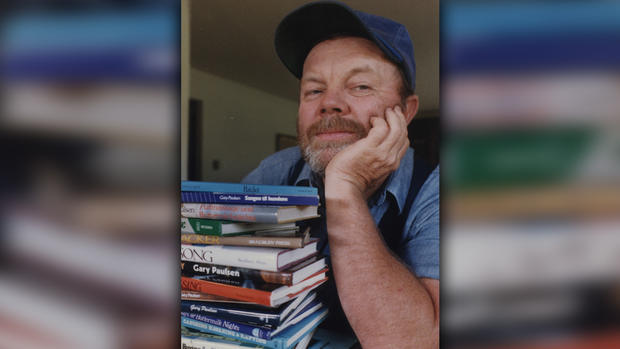

Gary Paulsen, Author Of 'Hatchet' And 'Dogsong,' Dies At 82

NEW YORK (AP) — Gary Paulsen, the acclaimed and prolific children's author who often drew upon his rural affinities and wide-ranging adventures for tales that included "Hatchet," "Brian's Winter" and "Dogsong," has died at age 82.

Random House Children's Books announced that Paulsen died "suddenly" Wednesday but did not immediately provide further details. Literary agent Jennifer Flannery told The Associated Press that he died at his home in New Mexico, where he lived with his third wife, Ruth Wright Paulsen, an artist who illustrated some of his work.

Author of more than 100 books, with sales topping 35 million, Paulsen was a three-time finalist for the John Newbery Medal for the year's best children's book and recipient in 1997 of the American Library Association's Margaret A. Edwards Award for lifetime achievement.

He was a Minnesota native who deeply identified with the outdoors, whether sailing on the Pacific Ocean, hiking in New Mexico or braving the cold of the Alaskan dogsled race, the Iditarod. For a time he lived in a cabin in rural Minnesota, where he finished his first novel "The Special War," and on a houseboat in the Pacific Ocean. He spent his latter years on a remote ranch in New Mexico, a bearded outdoorsman sometimes likened to Ernest Hemingway.

"I can't live in towns anymore," he told The New York Times in 2006. "The last time I was up in Santa Fe, I wasn't there 20 minutes before I brewed up, almost slugged a tourist on the steps of my wife's gallery."

Paulsen received the Newbery Honor prize for "Hatchet," "The Winter Room" and "Dogsong," about a young native Alaskan in search of a simpler past and the old ways. He also wrote hundreds of articles, poetry, historical fiction and such nonfiction works as the memoir "Gone to the Woods: Surviving a Lost Childhood," which came out earlier this year. His final novel, "Northwind," will be published in January by Farrar, Straus and Giroux Books for Younger Readers.

Many readers knew him best for his "Hatchet" novels, beginning with the eponymous 1986 release, in which 13-year-old Brian Robeson survives a plane crash and lives for weeks in the wilderness, relying in part on the hatchet his mother had given him. In an introduction for the book's 30th anniversary edition, Paulsen wrote that the novel "came from the darkest part" of his childhood, when books and the woods were his escapes from the pain of his parents' miserable marriage and his own social isolation.

"On my own, under the trees or on the lake or next to the river, I was protected and as far from danger as I'd ever been," he wrote. "In the wilderness, I was at ease. I learned the rules and I not only survived, I thrived. The woods and books are the only reason I got through my childhood in one piece."

The "Hatchet" series continued with "The River," "Brian's Winter," in which Paulsen imagined an alternate ending for the first novel, "Brian's Return" and "Brian's Hunt." He also turned out such series as the Francis Tucket adventure books and Murphy Westerns.

Paulsen, who grew up in Thief River Falls, Minnesota, had all too much personal experience to draw from for his work. He would recall his parents becoming so debilitated by rage and alcohol that he was essentially taking care of himself by his early teens, even hunting for his own food with a makeshift bow and arrow. He graduated from high school, raised his own tuition money to attend Bemidji State University and, in his early 20s, served in the U.S. Army. He had been a devoted reader since his teens, when he stopped into a local library on a freezing day, and in his mid-20s felt such a compulsion to write that he abruptly left his job as an aerospace engineer in California.

"The need to write hit me like a brick. I had a career and a family and a house and a retirement plan and I did all the things that responsible grown-ups do until suddenly, irrevocably, I knew had to write," he explained in the introduction to the "Hatchet" anniversary edition. "I edited a grubby men's magazine and, every night, I slaved over short stories and articles for two editors who ripped me to shreds every morning.

"They didn't leave a single sentence unscathed, but they taught me to write clean and fast. And the dance with words gave me a joy and a purpose I had been looking for my entire life."

(© Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.)