BCA Working To Match Missing With 100s Of Bones

MINNEAPOLIS (WCCO) -- Granite gravestones mark the lives once lived -- people remembered, cherished and loved.

But this simple and traditional final dignity is not afforded to Minnesota's missing persons.

"These all came in together," said Hamline anthropologist Sue Myster.

At the Midwest Medical Examiner's lab in Ramsey, Myster is examining 100 sets of both complete and partial human remains for answers. None is more important than a basic, who?

Looking at various bones arranged on a table, Myster said, "They represent three individuals -- two adults and two bones of a child."

The bones are just a fraction of the 100 cases of unidentified remains gathered over decades in Minnesota. A wide assortment of men, women and children.

"You really start to think that something has to be done and what can we do to help identify these people and send them home," Myster said.

Each bone is painstakingly examined to determine the age, gender and ethnicity. An odontologist will also be analyzing jaw bones and teeth to help with the identifications.

It is time-consuming work that is part of a first-ever project at the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension.

"And at the time their loved ones went missing, DNA wasn't an option," said the BCA's Cathy Knutson.

Knutson heads the BCA's forensic science laboratory, where the cutting-edge work is being done. Supported by an FBI grant, the goal is simple. They will attempt to identify as many remains as possible by matching the DNA profile to that of the missing person's immediate relatives.

"We have the technology now to go back to those individuals to use the advancements we have been able to come up with the past few years and serve these unidentified individuals and give them back their names," Knutson said.

After Myster's examination, the remains are sent to the BCA's St. Paul lab where the bone fragments are prepared for DNA extraction. Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is the unique biological fingerprint of the human cell.

"The two types of bone samples that we get the best result from tend to be femurs and then actually teeth,"

the BCA's forensic scientist Ann Gross said.

From a bone chip the size of a dime, the sample is pulverized into a powder. Then, hydrated in a tiny vial which is run through a computerized machine, revealing the DNA.

For the project to work they'll need to compare DNA of a relative to that DNA extracted from a bone. That's done by sending out sampling kits, which allow a relative to gather their own DNA by simply taking a cheek swab.

"I think it will be really incredible for us to be able to do that," said Kris Rush, who heads the state's Missing Persons Clearinghouse.

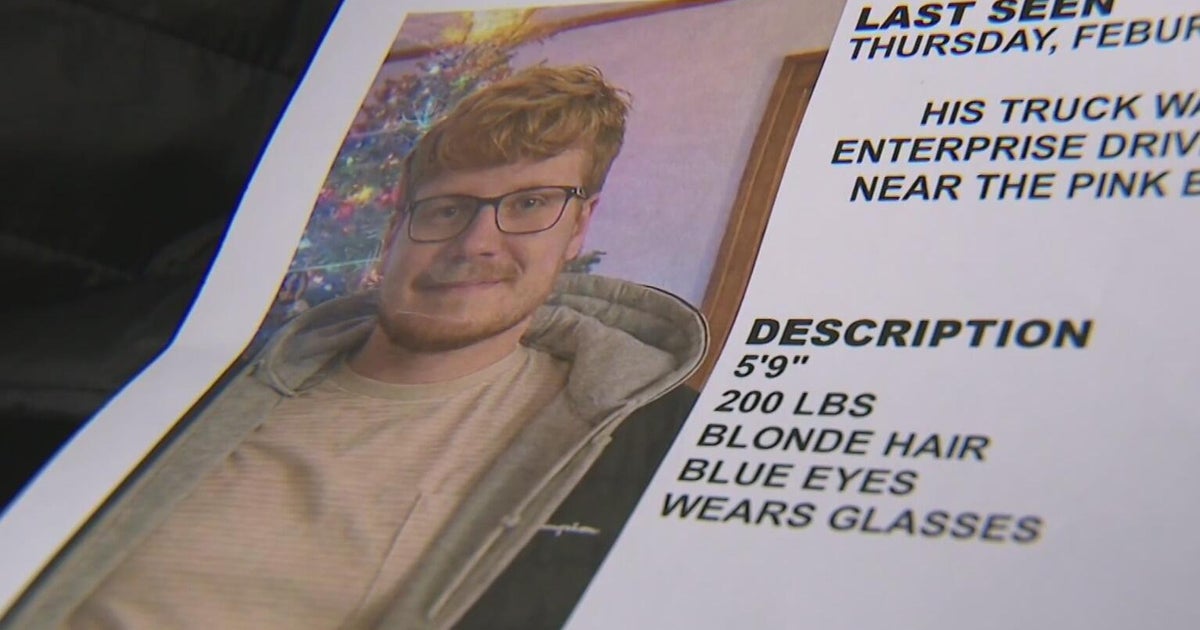

It is a database of names of individuals who so suddenly and tragically disappeared from society.

"You know that the unidentified that we have in those missing persons cases, one of those has to be a match, somebody out there is looking for that unidentified person," she said.

Even the missing who were never reported. With each family profile added, it's just a matter of time before matches are made and the missing, are no more.

"You sit here and look at all these unidentified sets of human remains," Myster said, "and you know there are people waiting for them, you know there are."