Alcoholics Find 'Safe' Place To Drink

ST. PAUL (WCCO) -- Sitting in an office at a St. Paul cremation and funeral service, 32-year-old Aimee Hallen recalls the police phone call on Saturday.

"They were looking for the next of kin," said Hallen, as she wiped away her tears.

In a strange, yet very real way, her sudden grief felt a bit awkward since she's reflecting on a father she barely knew.

"I know that he's lived a hard life. I know that he's lived on the streets. I know that he has worn out his welcome at many places," Hallen admitted.

Hallen's father was 55-year-old Ralph Stansbury, who battled a lifelong addiction to alcohol. For Hallen, softening the shock of Saturday's sudden phone call was the knowledge that her estranged father wasn't found frozen under a bridge.

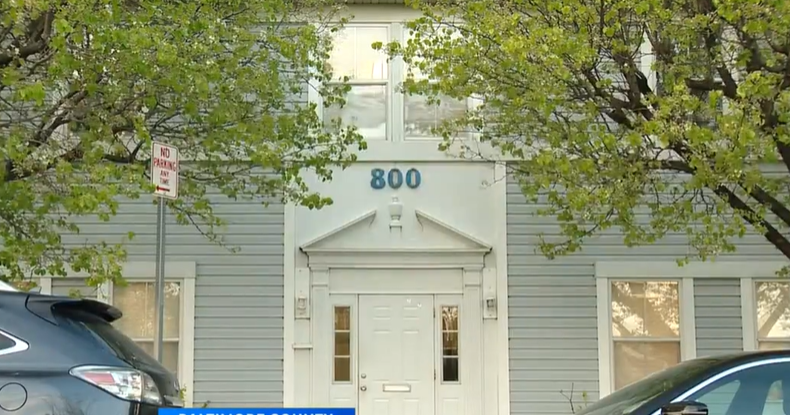

Stansbury died a quiet death while sleeping in his simple room at St. Anthony Residence.

"Pretty basic," is how site manager Bill Hockenberger described client's quarters.

The residence for Ramsey County's chronic alcoholics is operated by Catholic Charities. The mission is not to treat or cure alcoholics of their addiction, but rather to reduce harm -- to both themselves and others.

"The client that moves in here pretty much had their last fight. They're at a point in life where they've lost their housing so many times that they know what they need," explained Hockenberger.

And what they need, said Hockenberger, is a safe and simple place to stay. Everyone who stays at the facility has a couple of things in common -- they are all chronic alcoholics who've failed many attempts at treatment and they've spent a good share of their time living on the streets.

Hockenberger, himself a recovering alcoholic, said that's because they've exhausted most ties to family and burned bridges of support.

"Bad things happen on the streets," said resident Paul Schiller.

At 54, Schiller's home is now a 10-foot-by-10-foot room built of concrete block walls. It's much like a college dorm with room enough only for a single bed, a television and a bedside table.

"There's been better days in my life, but this is where I ended up," explained Schiller.

But what makes St. Anthony Residence so different from conventional treatment programs is that if Schiller or any of the residents want to drink, they still can.

Although drinking is not allowed in their private rooms, they are free to smoke and drink on an outside patio. Residents have to buy their own alcohol with whatever meager income they can scrape together.

Schiller said he often goes "canning," by collecting aluminum beverage cans and turning them in for a few dollars.

However, any alcohol brought into the building has to be checked at the front desk. Staff will place the alcohol in a locked room and turn it over upon request.

"Mainly safety and it's part of harm reduction model. We can control and let them monitor their drinking a bit," said Hackenberger.

Catholic Charities director of housing and emergency services, Tracy Berglund said, giving chronic alcoholics housing reduces the cost to everyone.

"There are studies that find when folks get housing, their drinking reduces," she said.

Then there is the cost comparison of housing people at $42 per day versus the thousands of dollars spent on each trip to a detox center or hospital emergency room.

"Most of our folks have gone to treatment multiple times. We get a majority of our referrals from Ramsey County detox," said Berglund.

Instead, St. Anthony Residence provides the 60 residents with three meals per day as well as necessary medical services provided by an on-site nurse.

Still, some critics have said that allowing chronic alcoholics to continue drinking is a bit like giving up on any possible rehabilitation. Berglund said the fact remains that treatment only works when the person is amenable to it.

"It helps to erase the pain," said Schiller. He said he drinks whenever he feels the need.

And for estranged loved ones like Aimee Hallen, who now grieves her father's death, it is a battle that some will never win. To her, what matters most is knowing a loved one spent their last days with a sense of dignity -- not wasting away on the streets.

To Hallen, what gives her comfort is the fact, "that he passed away in his sleep in a place that people knew he had passed away and could handle him properly."