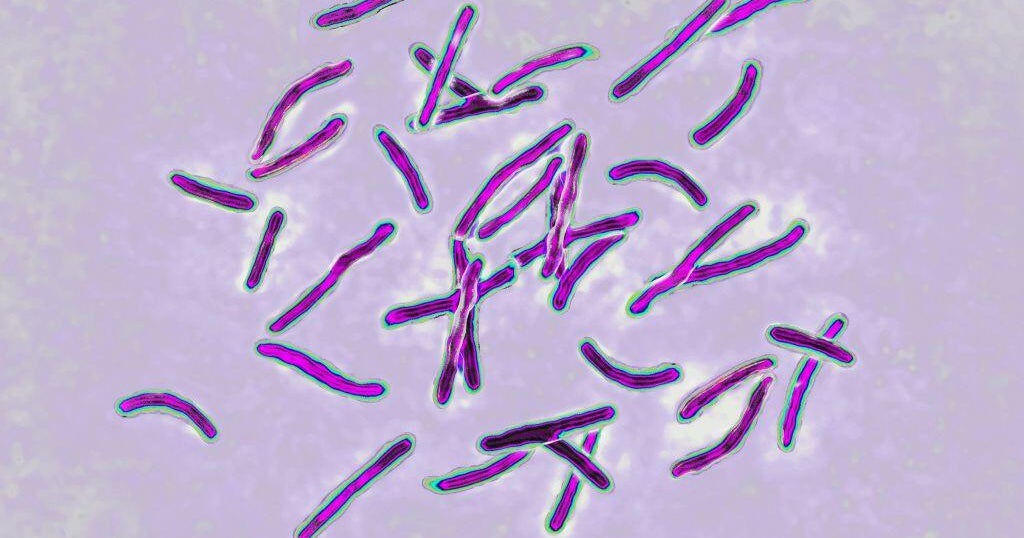

Study: COVID-19 Reinfection Is Rare, Severe Disease Even Rarer

MIAMI (CNN) -- When people got reinfected with COVID-19, their odds of ending up in the hospital or dying were 90% lower than an initial COVID-19 infection, according to a new study.

The study published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine found that there were few confirmed reinfections among 353,326 people who got COVID-19 in Qatar, and the re-infections were rare and generally mild.

The first wave of infections in Qatar struck between March and June of 2020. In the end about 40% of the population had detectable antibodies against COVID-19. The country then had two more waves from January through May of 2021. This was prior to the more infectious delta variant.

To determine how many people got reinfected, scientists from Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar compared the records of people with PCR-confirmed infections between February of 2020 and April 2021. They excluded 87,547 people who got the vaccine.

Researchers found that among the remaining cases there were 1,304 reinfections. The median time between the first illness and reinfection was about 9 months.

Among those with reinfections, there were only four cases severe enough that they had to go to the hospital. There were no cases where people were sick enough that they needed to be treated in the intensive care unit. Among the initial cases, 28 were considered critical. There were no deaths among the reinfected group, while there were seven deaths in the initial infections.

"When you have only 1,300 reinfections among that many people, and four cases of severe disease, that's pretty remarkable," said John Alcorn, an expert in immunology and a professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh who was not affiliated with this study.

The study has limits. It was done in Qatar, so it's not clear if the virus would behave the same way anywhere else. The work was done when the alpha and beta variant were the cause of many re-infections. There were 621 cases where it was undetermined and 213 from a "wild type" virus. There was no mention of the delta variant, which is now the predominant strain. That could have an impact on the number of reinfections.

Earlier studies have shown that natural immunity lowers ones risk of infection. One study done in Denmark published in March found that most people who had COVID-19 seemed to have protection from reinfection that remained stable for more than six months, but a check of the demographics of who was getting infected again showed it was mostly people 65 and older. That study does not make it clear how long protection lasts, and neither does the new Qatar study.

Alcorn's own research on natural immunity shows that antibody levels also vary significantly from person to person. Scientists still don't know what level of antibodies is protective, but in some cases, levels after infection may not be enough to keep someone from getting sick again.

"It needs to be determined whether such protection against severe disease at reinfection lasts for a longer period, analogous to the immunity that develops against other seasonal 'common-cold' coronaviruses, which elicit short-term immunity against mild reinfection but longer-term immunity against more severe illness with reinfection," the study said. "If this were the case with SARS-CoV-2, the virus (or at least the variants studied to date) could adopt a more benign pattern of infection when it becomes endemic."

Dr. Kami Kim, an infectious disease specialist who is not affiliated with this study, said people need to be careful not to come away with the wrong impression that it means people don't need to get vaccinated if they've been sick with COVID-19.

"It's sort of like asking the question do you need airbags and seat belts?" said Kim, director of the University of South Florida's Division of Infectious Disease & International Medicine. "Just because you have airbags doesn't mean that seatbelts won't help you and vice versa. It's good to have the protection of both."

Kim said it isn't worth taking your chances with the disease, particularly because an infection could bring with it long-term effects. "The incidence of long-Covid is way higher than the risk of getting a vaccine," Kim said.

Also vaccinations don't just protect an individual from getting sick, it protects the community.

"Modern medicine is much better, and people get cancer and survive and autoimmune diseases and thrive. Unless you are super close, you don't always know who is vulnerable to more severe disease, and you literally could be putting people you care about at risk if you get sick and expose them," Kim said. "Without vaccination you can't go back to a normal life."

Limiting the number of illnesses also limits the potential of more variants to develop, variants that could be even more dangerous than what's in circulation now.

Alcorn said there's another important lesson from this study.

"Vaccines are still our best method to get to the same place these people that have been infected are, absolutely," Alcorn said. "The major takeaway from this study here is that there's hope that through vaccination and through infection recovery that we'll get to the level where everybody has some level of protection."

(© 2021 Cable News Network, Inc., a WarnerMedia Company. All rights reserved.)