MSD Public Safety Commission eyes threat assessments, reporting ahead of new school year

FORT LAUDERDALE - The state commission created to address school-safety issues after the 2018 mass shooting at a Parkland high school is targeting inconsistencies in the ways schools assess threats, conduct active-assailant drills and report incidents.

The Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission, which met Tuesday in Sunrise, was extended through summer 2026 under a school-safety law signed in June by Gov. Ron DeSantis.

After recent mass shootings such as the killing of 19 children and two teachers at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, the commission discussed what members characterized as a need for more consistent guidelines that schools can follow to prevent dangerous incidents.

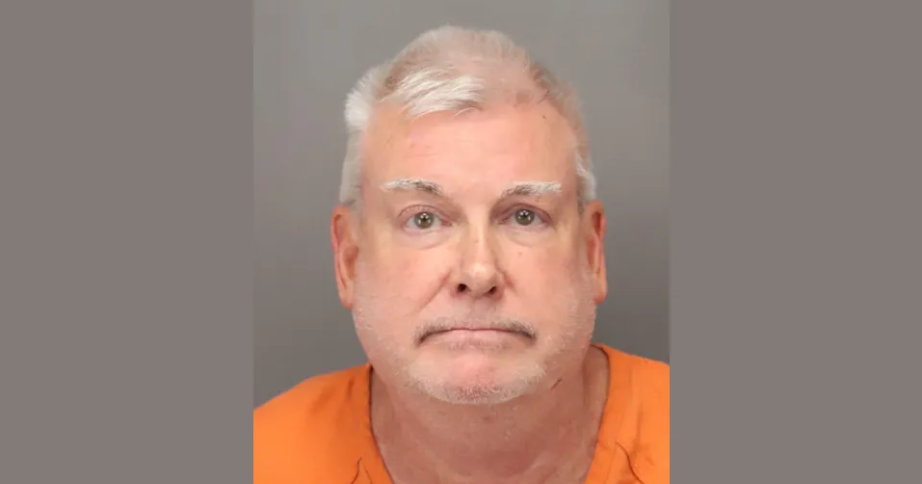

"One of the things that I know works is, when you're training people, you've got to give them as hard and fast rules as you can. People like hard and fast rules. You have to minimize the subjectivity, you've got to give them that framework," said Pinellas County Sheriff Bob Gualtieri, who is chairman of the commission.

As an example, Florida schools are required to have what are known as threat-assessment teams to comply with a 2018 safety law that passed after 17 students and faculty members were murdered at Stoneman Douglas High. Each team must include a law enforcement officer, a school counselor, an instructor, and an administrator.

While Florida schools use a common "instrument" called the Comprehensive School Threat Assessment Guidelines, they don't have a common threat-assessment process or reporting system.

A commission document described a patchwork of reporting systems, with 18 districts using dedicated software systems provided by four vendors. Two districts have developed their own systems, 21 districts are using "some aspect of their student information system," nine districts are using "pen and paper" and 14 districts are using Excel, Google Docs or similar software. Five districts did not respond to the survey.

Miami-Dade schools were mentioned.

"Five hundred and thirty schools, 350,000 students, they reported to the office of Safe Schools that they did 277 threat assessments for the 2020 - 2021 school year. That is 0.8 threat assessments per one thousand students. That's not even on per school," said Gualtieri.

Gualtieri said he's been meeting with Miami-Dade's new school Superintendent José Dotres.

"From what I see it's all encouraging, it's all positive, and there are improvements that are being made," he said.

Broward schools Superintendent Dr. Vickie Cartwright gave the commission an update on their progress, including beefing up school safety and threat assessment.

"The Broward County Public School Board approved the creation of a new behavioral threat assessment department under the safety, security, and emergency preparedness division," she said.

Gualtieri said he's seen an improvement in Broward.

"I think they went from a place in threat management and threat assessment in Broward County where it was effective to just the opposite. I think it's a model for the way it should be done," he said.

Commission member Mike Carroll, a former secretary of the state Department of Children and Families, said school districts would benefit from guidelines that are more clear.

"We need to ... put out some really consistent and firm requirements, and reporting requirements, in a singular document for districts to use. Because it's just all over the map," Carroll said.

Gualtieri also pointed to inconsistency in the reporting of threats among individual schools and districts, as many are not including students' threats of self-harm in their data.

"As we know, threats of self harm can transition into threats of harm toward other people. So, the threat-assessment teams, when they're ... convening, and whatever they're doing with threats of self harm, many districts are not incorporating that in their statistics," Gualtieri said.

Gualtieri proposed that the commission put together a work group that, over a 90-day period, would come up with recommendations.

"We have a discussion about it here, debate it, go through it, come up with a proposal from this commission that either goes to the State Board of Education so that they can come up with rules for a statewide model, or we take it to the Legislature and have it put in law so that we have this consistency. Because if we don't have that, we're going to have this discussion in two years," Gualtieri told the commission.

The commission also is expected to form a work group to craft a model active-assailant response policy for law-enforcement agencies. Gualtieri recommended that the group include representatives from the Florida Police Chiefs Association, the Florida Sheriffs Association, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, emergency responders and a school superintendent.

"That way, we make sure that those small agencies who don't have a policy or agencies, that don't have the most effective policy, have something to go by. And that we don't end up in a situation like a Uvalde, or like anything else, and it's because there hasn't been an effective evaluation of their practices, procedures, and policy," Gualtieri said.

Lawmakers eyed improvement of assailant drills during this year's legislative session.

The new school-safety law added a requirement for active-assailant drills that mandates law-enforcement officers responsible for responding to school emergencies "must be physically present on campus and directly involved in the execution of active assailant emergency drills."

Another work group planned by the commission would be geared toward improving accuracy in reporting incidents of crime, violence, and disruptive behaviors on campuses. Such incidents are reported through a state data collection system called School Environmental Safety Incident Reporting, or SESIR.

The system allows for schools to log incidents that fall into 26 categories, which are divided into four "levels" based on severity of threats.

Commission member Max Schachter, whose son Alex was killed in the Parkland shooting, said improving reporting accuracy can help schools get the help they need.

"The reason we want this data accurate is so we can use this data to surge resources to schools that need it most, and incentivizing principals to report accurate numbers," Schachter said.