Legal Immigrants Avoiding Health Care Due To Deportation Fears

Follow CBSMIAMI.COM: Facebook | Twitter

MIAMI (CBSMiami/AP) — President Donald Trump's tough stand on immigration has had an unexpected effect.

Some immigrants in the country legally are foregoing public health services and federally subsidized insurance plans because they fear the information they provide could be used to identify and deport relatives who are living here illegally, according to health advocates across the country.

After Trump became president a year ago, "every single day families canceled" their Medicaid plans and "people really didn't access any of our programs," said Daniel Bouton, a director at the Community Council, a nonprofit that specializes in health care enrollment for low-income families.

The trend stabilized a bit as the year went on, but it remains clear that the increasingly polarized immigration debate is having a chilling effect on Hispanic participation in health care programs, particularly during the enrollment season that ended in December.

Bouton's organization has helped a 52-year-old housekeeper from Mexico, a legal resident, sign up for federally subsidized health insurance for two years. But now she's going without, fearing immigration officials will use her enrollment to track down her husband, who is in the country illegally. She's also considering not re-enrolling their children, 15 and 18, in the Children's Health Insurance Program, or CHIP, even though they were born in the U.S.

"We're afraid of maybe getting sick or getting into an accident, but the fear of my husband being deported is bigger," the woman, who declined to give their names for fear her husband could be deported, said through a translator in a telephone interview.

Hispanic immigrants are not only declining to sign up for health care under programs that began or expanded under Barack Obama's presidency -- they're also not seeking treatment when they're sick, Bouton and others say.

Enticing Hispanics to take advantage of subsidized health care has been a struggle that began long before Trump's presidency.

Hispanics are more than three times as likely to go without health insurance as are their white counterparts, according to a 2015 study by Pew Research Center. Whites represented 63 percent, or 3.8 million, of those who signed up for Affordable Care Act plans last year compared to 15 percent, or just under a million, Hispanics, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The reasons vary, but some have always feared deportation, regardless of who is in office.

Recent events have not helped. Despite initial signs of a compromise agreement, Trump now isn't supporting a deal to support young people who identified themselves to the federal government so that they could qualify for protection against deportation despite being brought to the U.S. illegally as children.

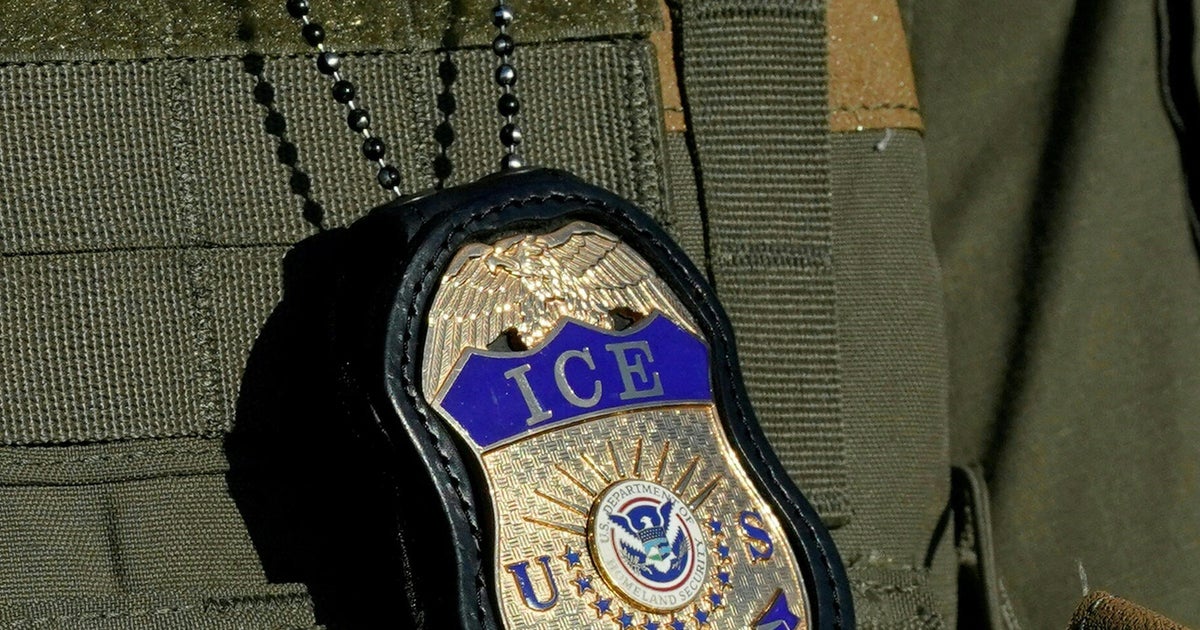

In Okeechobee, home to many immigrant farm workers, green-and-white-striped immigration vehicles were spotted driving around town and parking in conspicuous places last spring and summer. After a few immigrants were picked up and deported, health advocates said patients canceled their appointments, waiting until immigration officials left to reschedule them.

Last fall, Border Patrol agents followed a 10-year-old immigrant with cerebral palsy to a Texas hospital and took her into custody after the surgery. She had been brought to the U.S. from Mexico when she was a toddler.

In Washington state and Florida, health workers report that immigrant patients start the enrollment process, but drop out once they are required to turn in proof of income, Social Security and other personal information.

In a survey of four Health Outreach Partner locations in California and the Pacific Northwest, social workers said some of their patients asked to be removed from the centers' records for fear that the information could be used to aid deportation hearings.

The dilemma has forced social workers at Health Outreach Partner to broaden their job descriptions, Gomez said. Now, in addition to signing people up for health insurance or helping them access medical treatments, they are fielding questions about immigration issues and drawing up contingency plans for when a family member is deported.

"That planning is seen as more helpful and immediate to their patients than their medical needs right now," he said.

(© Copyright 2018 CBS Broadcasting Inc. All Rights Reserved. The Associated Press contributed to this report.)