Fear Keeps Many In Miami From Reporting Child Abuse

MIAMI (CBS4) – Fear of government intervention in Miami-Dade's heavily Hispanic and Haitian communities has led to the county having one of the lowest rates, among Florida's larger counties, for calls to the state's child abuse hotline.

Calls to the state's child abuse hotline from Miami-Dade are about 20,000 annually, which is the same as Broward and Orange counties even though those counties are much smaller.

Child welfare officials worry that Miami-Dade investigators aren't removing children despite warning signs of abuse because of a statewide push to safely keep children in the home and work with their families.

"Miami keeps you up at night worrying because you know there are calls that aren't coming in and cases we aren't hearing about," said Alan Abramowitz, a former family safety director for the Department of Children and Families. He now heads the state guardian ad litem program, which provides volunteers to represent abused and neglected children in court.

Hotline calls are the primary way that authorities investigate and consequently remove a child.

That's one reason child removal rates in Miami-Dade were 1.6 per 1,000 children in 2010. That's up slightly from 1.4 per 1,000 in 2009 but still far less than neighboring Broward County, where officials removed at a rate of 2.3 per 1,000 children in 2010. In Hillsborough County, the removal rate was 4.2 per 1,000, according to data obtained by The Associated Press.

Removal rates that dip below 3 per 1,000 mean kids are at risk and more than 6 signals too many kids are being removed, Abramowitz said.

Many in Miami-Dade attribute the low removal rate to the Cuban and Haitian communities' fear of government fostered by the repression in their home countries. Experts say those communities' widely view the abuse hotline and general child welfare services as punitive instead of a system designed to help.

Child court Judge Cindy Lederman recently had a Haitian mother in her courtroom who was accused of neglect after she did not take her accidentally injured child to the hospital.

"I'm from Haiti and we hear that you just take children away for nothing in this country and I was afraid," Lederman recalled the mother saying.

Miami grandmother Maria Diaz said she doesn't trust child welfare workers and would prefer to handle problems within the family, especially after reading headlines of children harmed while in the state's care.

She would be reluctant to call the hotline.

"In the news lately it seems like a lot of things fall through the cracks. It doesn't seem like people are who supposed to be doing their jobs are doing their jobs," Diaz said. "If you have a sound family and they're able to take care of it in the family, it's (better) for the children.

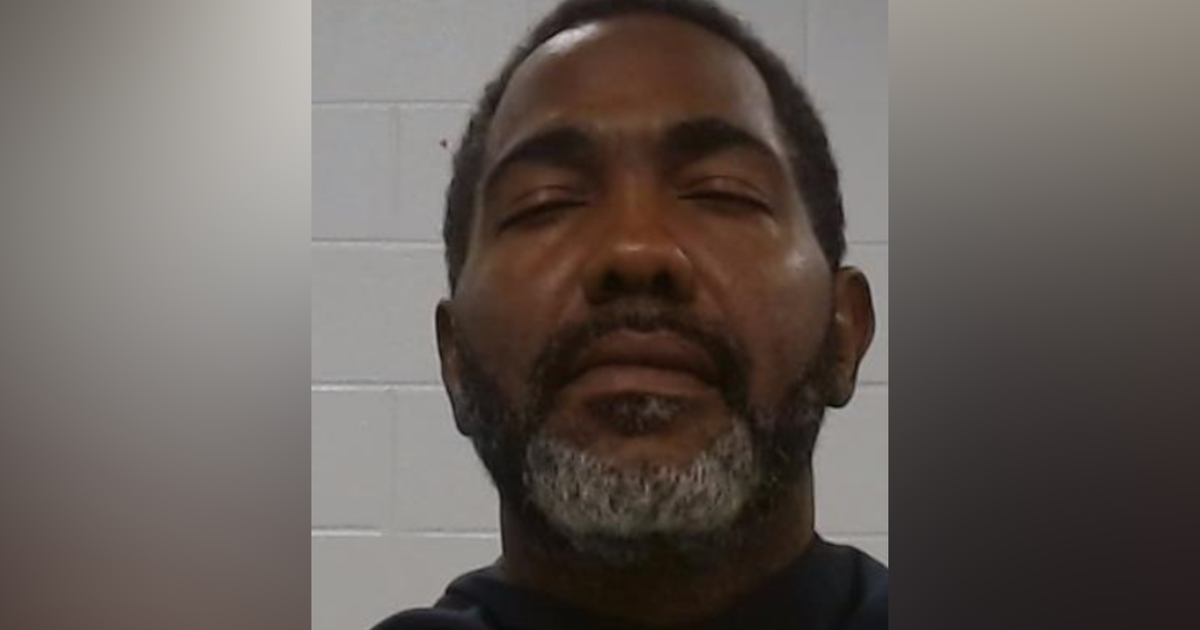

Her grandchildren attend the same elementary school as the 10-year-old twins found in their adoptive father's truck on a busy interstate on Valentine's Day. Nubia Barahona's body was partially decomposing in the back. Authorities say her parents beat her to death. Victor Barahona, who survived, suffered serious burns after being doused with a toxic chemical. Their parents have pleaded not guilty to first-degree murder and several child abuse and neglect charges.

After Nubia's widely publicized death, hotline calls spiked in Miami from 2,066 in February to 2,701 in March — a 31 percent jump. Still, the number of calls wasn't proportional to Miami's population. Welfare experts say increased calls are common after high-profile child abuse cases. Calls also increased in Broward and Palm Beach counties.

Cheryl Little of the Florida Immigrant Advocacy Center said many of the Hispanic and Haitian immigrants she works with fear any police contact will bring questions from immigration officials, even if that's not the case.

"I think it's been very detrimental in terms of our communities," Little said. "The folks who are victims of a crime or who have witnessed a crime are afraid to come forward."

But even when abuse is reported, children are sometimes not removed. Individual investigators and judges may reach different conclusions in the highly subjective process about removing a child, although the standards are the same. The role has come under scrutiny after someone called the hotline in February alleging Victor and Nubia were being locked in a bathroom for days with their hands and feet bound by their adoptive parents.

An investigator visited the home and filled out a form saying the children were not in danger, even though she never saw them. That investigator never called police during a futile four-day search for the twins.

DCF officials said they are overhauling the role of child investigators in the wake of that case.

"Certainly the question of removal, which is one of the most important decisions they make, is going to be a central part of that evaluation," spokesman Joe Follick said.