Will Congress finally overhaul No Child Left Behind?

The House of Representatives passed a bill to update the No Child Left Behind law on Wednesday evening, just over a day after a separate education reform bill hit the Senate floor. The twin developments raise the possibility that an overhaul of the federal government's education policies might soon reach President Obama's desk.

No Child Left Behind (NCLB) was passed in 2001 as the latest iteration of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. It expanded the federal role in education policy in several ways - by pushing states to adopt strong academic standards, by forcing states to measure student achievement on an annual basis to track whether they're meeting those standards, and by sanctioning schools that failed to demonstrate student improvement.

The bill was credited with some successes, notably a narrowing of the achievement gap between white and minority students, but it also came under criticism from both the left and right as states and school districts struggled to meet the benchmarks it set.

From the left, teachers unions and other education interest groups complained that the emphasis on testing placed educators under often-unrealistic expectations, forcing them to "teach to the test" rather than exercising their professional judgment. They also complained that the sanctions on failing schools were too punitive and that the government did not provide resources to help underperforming schools improve.

From the right, conservatives complained about federal overreach, particularly the law's push for states to adopt rigorous standards. They warned that the Common Core standards -- drafted by the states in the wake of NCLB but encouraged by the federal government -- have given federal authorities too much power in a policy arena that has customarily been left to the states.

The Senate bill introduced Tuesday would scale back the federal government's role in education, giving states more control over what kind of standards to set and how to use the annual testing to measure student performance. It's a compromise that has already won plaudits from both conservative and liberal members of the Senate, but it still faces a long road to passage. Some Senate Democrats are angling for changes to the bill to boost civil rights protections and make the education system more responsive to underperforming students.

The House bill that passed Wednesday, for its part, is significantly more conservative than the Senate measure -- not a single House Democrat voted in favor of passage. Whether the two chambers can iron out their differences in a conference committee remains to be seen.

Moreover, Mr. Obama's administration has already voiced reservations about both bills, threatening to veto the House's measure and pushing senators to add language to "strengthen school accountability to close troubling achievement and opportunity gaps."

And to cap it off, the intensifying 2016 presidential election, in which a number of sitting senators are candidates, is sure to throw a monkey wrench into the process as Democrats and Republicans alike seize the opportunity to sound off on education policy.

Here's a look at the treacherous road ahead for the education bill.

Bipartisan movement in the Senate - but can it last?

In April, the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee passed the "Every Child Achieves Act" unanimously. The bill was the product of painstaking negotiations between the panel's chairman, Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-Tennessee, and the ranking Democrat, Washington Sen. Patty Murray.

The bill, as noted before, aimed to diminish the federal role in education policymaking. It would allow states to decide whether to evaluate teacher performance and how it should be measured. It would require states to improve failing schools but provide them with more flexibility to do so than they enjoy under the current system, which spells out four prospective turnaround methods. It would extend the requirement for states to include student testing results in their accountability systems but allow each state to determine how much weight that testing should carry (other pertinent factors include graduation rates, workforce readiness, and English proficiency of non-native speakers.)

Perhaps most politically important is the bill's clarification that the federal government cannot interfere with each state's ability to set academic standards. That measure is intended to placate critics who say current law allows the federal government to promote "Common Core" standards by tying federal grant money to a state's adoption of those standards. The new law would urge states to develop "challenging" curriculum but forbid the federal government from making the adoption of federal-backed standards a precondition of financial support.

It seemed like a promising start for a bipartisan overhaul - the supporters in committee included such ideologically disparate figures as Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul.

"I think we've made tremendous progress," Murray told reporters on Wednesday. "We've made a lot of improvements in it, we're gonna have a really good debate on the floor, there's gonna be amendments offered on both sides."

Those amendments, though, could change the substance of the bill fairly dramatically, and potentially imperil its wide bipartisan support. Democrats are pushing changes to safeguard civil rights protections. Politico reports that Warren, among others, is pushing revised language "requiring states to track performance of poor and minority students and do something to improve schools that are falling down on the job."

Republicans, by contrast, would like to provide students in failing schools more opportunities to switch schools - a push for school choice that would risk driving away Democratic support. Some conservative groups are also agitating for changes that would allow individual students and schools to opt out of the bill's testing and performance mandates.

Over the next week or so, those amendments will either be discarded or implemented as the Senate plows its way through a series of roll call votes. The product that emerges from the floor debate, if passed, will go to a conference committee with the House, which has some very different ideas about how to reform U.S. education policy.

House passes a partisan bill

In contrast to the bipartisan process in the Senate, the House on Wednesday passed the "Student Success Act" on a narrow, partisan vote, with 218 lawmakers in favor and 213 opposed. Every House Democrat voted against the measure and 27 Republicans bucked their leaders to do the same.

The bill cleared the Education and the Workforce Committee back in February, even though Democrats had strong objections to it. President Obama and his party oppose the bill in part because of its "portability" provision, which would let public funds follow a low-income student from school to school. Democrats argue that would divert funds from schools that need it the most.

The legislation eliminates dozens of federal education programs that Republicans say are redundant. It also repeals federal requirements for teacher quality and supports magnet schools and charter schools, among other things. It forbids the federal government from encouraging the adoption of any specific type of academic standards. And it includes an amendment, championed by the conservatives, that would allow parents to exempt their children from standardized testing.

Rep. Steve Scalise, R-Louisiana, said Wednesday that the bill "advances the strength and ability for local communities to be more directly involved in their education without coercion coming from the federal government."

House Democratic Whip Steny Hoyer, D-Maryland, said earlier this week that while Democrats oppose the House bill, the Senate's bill is something they would be willing to entertain.

White House watches with curiosity, caution

As negotiations over the legislative overhaul continue in Congress, the White House seems keenly aware that it could disrupt the whole process by interfering too much.

"Right now, we certainly are intrigued by the kind of bipartisan effort that is underway on Capitol Hill, and we, generally speaking, want to be supportive of that effort," White House spokesman Josh Earnest said Monday.

He acknowledged that President Obama has been working behind the scenes with Democrats and Republicans on the effort, even though the president hasn't said much publicly about it.

Back in February, the White House put out a strong veto threat against the House's Student Success Act, but its response to the Senate's Every Child Achieves Act has been more encouraging.

In a "statement of policy" released Tuesday, the White House called the Senate bill an "important step forward" in reforming No Child Left Behind. The administration commended several elements of the bill, such as its commitment to "to expand opportunities for America's children to attend high-quality preschool."

However, the administration also urged changes to several specific provisions. For instance, the bill should "cap the amount of time spent annually on standardized testing," the administration suggested.

2016 Republicans on education

Although No Child Left Behind (NCLB) was the brainchild of a Republican president, it came to be viewed by many in the GOP as a symbol of federal overreach. Former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum has said he regrets his 2001 vote in favor of the law. Former Texas Gov. Rick Perry once called it a "monstrous intrusion into our affairs," adding of former President George W. Bush, "Look, I like George but that's not good public policy." Every GOP governor who is running for president or thinking of running for president comes from a state that sought a waiver from the law's requirements.

With NCLB in the middle of a complex rewrite, few of the Republican candidates have weighed in on the bill under consideration at the moment. Sen. Rand Paul, R-Kentucky, sits on the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions and joined his colleagues in unanimously supporting the draft crafted by the committee. Three other senators running for the GOP nomination - Marco Rubio of Florida, Lindsey Graham of South Carolina and Ted Cruz of Texas - will have to make a decision on a flurry of amendments and the final bill as the full Senate considers it this month.

Graham has long called for ways to make the law "more efficient, more user-friendly, less draconian, and less punitive." Rubio hasn't been vocal about NCLB, but he has objected to the Obama administration's attempts to get states to adopt its preferred reforms in exchange for waivers.

Cruz issued a statement that said Congress must "seize this opportunity to eliminate burdensome federal mandates and ineffective programs in order to restore decision making back to parents and students." He also said he will be pushing to include the "portability" provision, strongly opposed by Democrats, that allows education dollars follow students to a school of their choosing rather than the school for which they're zoned.

The law wasn't always the target of Republican criticism. During his 2008 presidential campaign, former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee said that NCLB was "often misunderstood and unfairly maligned as a total federal intrusion," and said that there was "a value of having a national effort to at least set high standards." He also called it "the best thing that ever happened in education." Nowadays, Huckabee says the Department of Education should be eliminated.

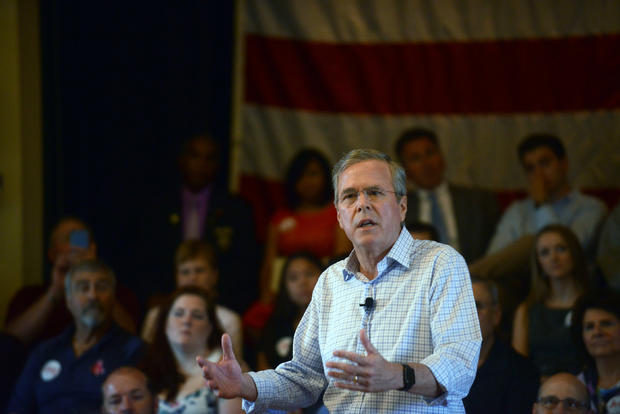

Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush has refrained from verbally attacking the law (which is, of course, one of his brother's signature domestic accomplishments). In a recent Washington Post op-ed, Bush wrote that the federal government should have a limited role in elementary and secondary education, but that they do have a role in creating transparency.

"Before the last reauthorization of ESEA in 2001, known as No Child Left Behind (NCLB), most states had no accountability system. They plowed billions of taxpayer dollars into education bureaucracies, often getting nothing in return. NCLB changed that by creating a common yardstick," Bush wrote. "Now, all states participate in the National Assessment of Educational Progress, a series of high-quality tests known as the Nation's Report Card. The results give us an apples-to-apples comparison among states. Annual testing and reporting also force states to confront their failures, especially the substandard education often offered to disadvantaged children."

"NCLB is far from perfect. It doesn't give states the flexibility they need, and the system can be gamed. But those flaws can be fixed in the reauthorization process," he concluded.

Bush himself seemed interested in helping to work on a reauthorization, according to an email he sent Education Secretary Arne Duncan in 2009 that was obtained by BuzzFeed.

The contemporary education boogeyman for most GOP politicians is the Common Core State Standards, and nearly every Republican candidate frames his or her education policy around their desire to eliminate Common Core and return more control over education to the states - even though many of those politicians once supported the state-authored educational standards.

The one exception is Bush, who has worked on education reform issues since leaving office. He argued during a speech last November before an education reform group he co-founded that Common Core should be the "new minimum" in student achievement, and he challenged foes of the program to offer a better alternative.

2016 Democrats on education

Democrats are far less likely to clamor about federal intrusion in education policy, but No Child Left Behind still doesn't have any strong defenders among those competing for the Democratic nomination. Hillary Clinton, like nearly all of her Senate colleagues, voted in favor of NCLB in 2001. But by the time she ran for president in 2008, she changed her tune, promising she would "put an end to the unfunded mandate called No Child Left Behind." She hasn't yet weighed in on the bill being crafted by the Senate.

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, an independent who is running for the Democratic nomination, has weighed in - he is a member of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, which unanimously backed the compromise bill to rewrite NCLB.

"I think it is wrong to judge schools solely on the basis of narrow tests. We have to work on what kind of criteria we really need," Sanders said in a statement after the Senate committee's vote. "What we in Vermont understand is a kid is more than a test. We want kids to be creative. We want kids to be critical thinkers. We also want schools held accountable for factors other than test scores, including how they meet the challenges of students from low-income families."

Sanders voted in favor of NCLB in 2001 as a member of the House.

As Mayor of Baltimore, Martin O'Malley fought Maryland's efforts to use NCLB to take control of some of the city's failing schools. But he's not opposed to federal intervention in education, and Maryland adopted the Common Core School Standards in 2013 under his leadership.

When he ran for Virginia's Senate seat in 2006, Jim Webb said he supported the aims of the NCLB, but thought more federal funding was necessary to help schools meet them. He declined to call for an outright repeal of the law.

And before he was seeking the Democratic presidential nomination, Lincoln Chafee was a Republican senator from Rhode Island who voted in favor of the 2001 NCLB law. But in 2013, while he was the state's governor (and an independent), Rhode Island received a waiver from the law's mandates.