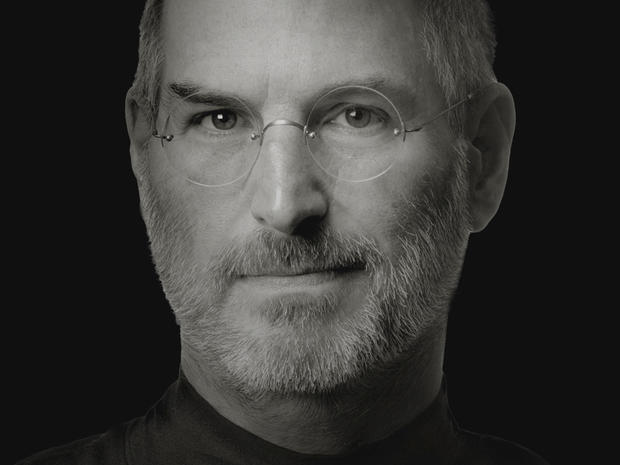

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

(MoneyWatch) On his last day as Apple's (AAPL) CEO on August 24, 2011, Steve Jobs said that the company's "brightest and most innovative days are ahead of it." Certainly that's true by one measure -- in the year since Jobs's death, Apple has become the largest company in the U.S. by market value.

Jobs died a year ago today of pancreatic cancer. He was 56. In the following gallery, CBS MoneyWatch blogger Erik Sherman looks at the iconic leader and the indelible mark he left on Apple -- and the world.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

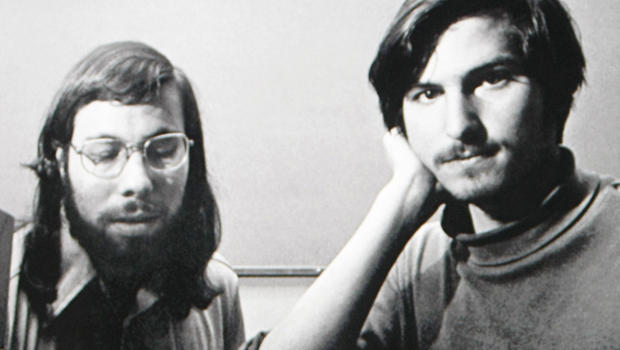

Jobs meets Woz

In 1971, Steve Jobs met genius computer engineer Steve Wozniak, who had dropped out of college to work for Hewlett-Packard (HPQ). Jobs was outgoing, Wozniak painfully shy. But the two had plenty in common -- they had both learned about electronics from their fathers and loved pulling pranks.

In fat, their first business venture was selling illegal "blue boxes," which let people make free long-distance telephone calls. Jobs would later look back at the "magical" experience of teenagers building a device from $100 worth of parts that could control massive telephone networks.

"Experiences like that taught us the power of ideas," he said in a video interview for the 1998 documentary, Silicon Valley: A 100 Year Renaissance. "If we hadn't have made blue boxes, there would have been no Apple."

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

Birth of a legend

The fledgling Apple needed money fast. Jobs sold his Volkswagen bus and Wozniak his programmable calculator, raising $1,300 to pay for parts. They introduced the Apple I on April Fools Day in 1976. Shortly thereafter, a local computer dealer placed a $50,000 order for 100 units.

Buying parts on credit gave the pair a month to pay off their bills. Jobs talked family and friends into helping them build the products. They completed the order, earned their first revenue and paid off the parts suppliers with one day to spare.

Jobs and Wozniak later met Armas Clifford (Mike) Markkula, a former Fairchild Semiconductor and Intel (INTC) manager who helped them write a business plan. Markkula also invested $92,000 of his own money and helped arrange a $250,000 credit line for the fledgling company. That gave Apple the necessary capital for its first hit product.

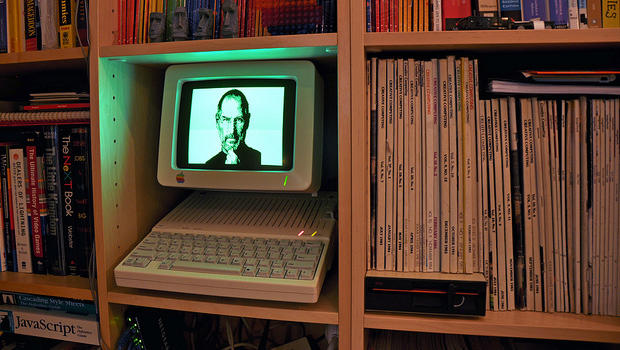

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

The Apple II cometh

With money in the bank, Apple Computer filed to incorporate on Jan. 3, 1977. Markkula insisted on seasoned management and brought in Michael Scott as the company's first CEO. But the major development was a new product Wozniak had slaved over: The Apple II. With color graphics, an attractive plastic case, built-in keyboard and easy-to-understand manuals, the Apple II was a revolution in design -- a fully working, integrated computer that looked like a consumer product.

Realizing that pre-packaged software would be key to selling computers for non-techies, Jobs beat the bushes for programmers who would start creating applications. (There would eventually be more than 15,000 software titles for the Apple II.) He also focused on marketing and PR. Apple became the first personal computer company to run ads in consumer magazines. Apple sold nearly 6 million Apple II computers over the next 15 years.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

Jobs sees the future

In 1979, Jobs visited Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center, better known as PARC, a legendary cauldron of digital creativity. Three key technology developments -- graphical user interfaces, object-oriented computing and computer networking -- convinced Jobs he'd just seen the future of computing. He made a deal with Xerox, allowing the company to invest $1 million in Apple in return for allowing Apple engineers to take two guided tours of the PARC. Xerox would live to regret that deal.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

Apple goes public

By 1980, Apple was a $118 million company and had grown to 1,000 employees. That December it went public in the biggest IPO since Ford Motor Company in 1954. By the end of the day, Apple had a market cap of nearly $1.8 billion, and Jobs was rich.

"I was worth over $1 million when I was 23," Jobs would later say in a video interview, "and over $10 million when I was 24 and over $100 million when I was 25. And it wasn't that important because I never did it for the money."

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

The Lisa

One year later, Jobs was in a jam. Apple had drawn on what it had learned from PARC and created the Lisa, a business computer named for Jobs's daughter (although Apple later came up with the face-saving acronym "Local Integrated Software Architecture"). Jobs had wanted to run the Lisa project, but his earlier failure on the the Apple III -- a disaster that resulted in a massive product recall and redesign -- led CEO Scott to turn him down. Jobs brooded for few months, but pulled himself out of his funk via a new skunkworks project that would redefine the company.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

The secret Macintosh

Although the Apple II had sold millions of units, the $10,000 Lisa limped along, with only 100,000 sold in the space of two years. Meanwhile, IBM's (IBM) PC had emerged as the new king of the personal computer market. It was a utilitarian affair, with no mouse, no graphical interface and a nerdy Microsoft operating system that catered to business users -- in short, just about everything that Jobs hated.

Inside Apple, an employee named Jef Raskin had been pushing a computer he called the Macintosh, a device that would be as simple to use as a kitchen appliance. Jobs took control of the project and added a mouse and graphic interface, just as he'd seen at PARC.

Jobs took young brilliant engineers off other projects, literally pulling a computer away from one of them. The group worked in a remote pressure-cooker of a building, where Jobs frequently threw people's work back at them until it was perfect. The team ran up a pirate flag on the roof. The message: Forget business as usual. Still, someone at the company had oversee corporate matters, and that would lead to Jobs's downfall.

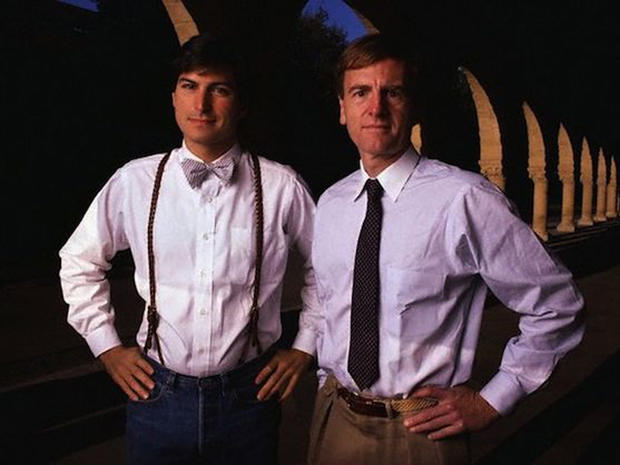

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

Jobs recruits Sculley

Meanwhile, Apple's management was in turmoil. Mike Markkula had served as CEO after replacing Michael Scott, but by 1983 was ready to retire. Jobs wanted the top job, but Markkula didn't trust his mercurial temperament. What Apple needed was an experienced manager who would know how to handle employees and how to represent the public company in its relationship with Wall Street.

Markkula wanted someone who understood consumer business. That's what he thought he'd found in Pepsi (PEP) vice president John Sculley, the youngest ever head of marketing at the soda company. Sculley had pioneered the use of consumer research and initiated major ad campaigns like the famous Pepsi Challenge, which aimed to show that people preferred Pepsi to Coke. Offered the Apple job, Sculley was still on the fence. Jobs flew to New York, stared at Sculley and said, "Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life, or do you want to come with me and change the world?" It was one of the best pitches Jobs would ever make -- and one of his biggest mistakes.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

An ad changes the world

Jobs planned a big splash for the Macintosh. In 1983, he commissioned movie director Ridley Scott to produce an eerie, Orwellian television ad. The spot showed lines of drably garbed people staring in trance-like obedience at a Big Brother-like figure on a giant TV set, until a lone woman runs through their ranks and flings a hammer that smashes the screen to pieces. The commercial, which ran during Super Bowl XVIII, closed with the words: "On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you'll see why 1984 won't be like '1984.' "

Despite -- or perhaps because of -- its striking imagery, the ad almost never made it on the air. Apple's board hated it and wanted to sell back the air time. The only reason it ran, in fact, was that Jobs had already converted Apple's sales force. He'd screened it for them the previous fall during the company's annual sales meeting. On a vast, dark stage, the young Jobs painted a picture of an industry too long dominated by IBM, which he characterized as wanting to destroy Apple to keep the computer market all to itself. The commercial ran, and even before it ended the audience had exploded in cheers and applause.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

Jobs gets the boot

The Macintosh was anything but an immediate hit. Its impressive user interface sucked up too much of the machine's resources, and there was too little software available. Unsold Macs piled up in the company's warehouse following a dismal 1984 holiday season. Sales were so bad that the company laid off a fifth of its workforce, closed three of its six manufacturing plants and reported its first quarterly loss.

Worst of all, Sculley blamed Jobs for the disaster and went to the board to demand his removal as a vice president and general manager of the Macintosh group. Sculley wanted Jobs to be chairman of the board and a public face of the company, not someone who could cause operational problems. Jobs got word and tried to get Sculley ousted instead. A majority backed Sculley, and by May Jobs was nothing but a figurehead.

"What can I say?" Jobs would say later. "I hired the wrong guy. And he destroyed everything I had spent 10 years working for, starting with me." He left in September. Around the same time, some software vendors began to understand what was possible with the Mac and wrote the first desktop publishing packages, harbingers of a wave of applications that would make Macs a must-have for many creative types. But Jobs would no longer be at Apple to appreciate it -- or to take credit.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

Into the wilderness

When Jobs walked away from Apple, he took a half dozen people with him to start a rival computer company. NeXT used everything Jobs had seen at Xerox PARC, just taken to the next level. The radical NeXT cube aimed to revolutionize computing on both the software and hardware fronts. While the machines themselves flopped, the NeXT software continued to make inroads among the technically minded. Jobs wanted to build the first computer for the 1990s, and in a way he did: Tim Berners-Lee wrote the first Web browser in 1990 on a NeXT. But the real importance of NeXT would be as a foundation for future Macs, iPhones and iPads.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

Jobs readies for his close-up

When Jobs left Apple, he sold his shares of the company and became an instant millionaire. In 1986, he bought the computer graphics division of Lucasfilm for $10 million and called it Pixar. Working with a talented stable of artists and engineers, he created a new era in animation. Pixar started with Luxo Jr., a charming short that created compelling characters out of computer-animated desk lamps.

To Jobs, Pixar represented something like the fusion of cutting-edge technology and the human soul -- an effort to create an entirely new, and yet still entirely satisfying, storytelling aesthetic using the new tools that technology had made available. The results: A string of hit films such as Toy Story, Monsters, Inc. and Finding Nemo.

These was possible only because Jobs kept the company financially afloat for years as it honed its skills and improved its tools -- solely because he believed Pixar could change the world of entertainment. The experience revolutionized his view of business.

"When these films take four years to make and they last for 60 or 100 years, you start to develop a longer focal length point of view than just the next six months," Jobs said on the Charlie Rose show in 1996. In 1995, the company went public in the biggest IPO of the year, beating out Netscape and making Jobs a billionaire. Ten years later, Jobs sold Pixar to Walt Disney (DIS) for $7.4 billion in stock, making him Disney's biggest shareholder and effectively killing off Disney's own storied hand-drawn animation shop.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

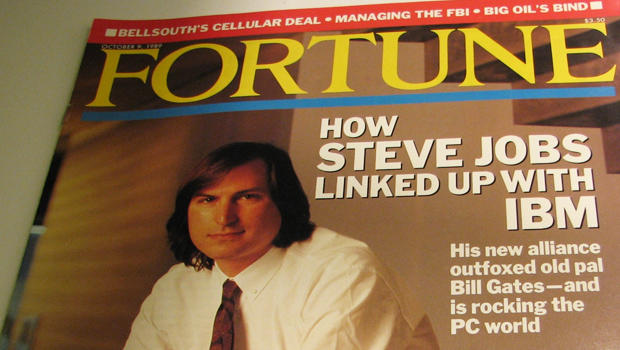

The prodigal son returns

In Jobs's absence, PCs had trounced the Mac in the marketplace. Apple suffered repeated reorganizations and layoffs; the board forced out Sculley, then sacked his replacement. Executives fled. In the mid-1990s, Microsoft introduced Windows 95, which finally gave PCs rough graphical-interface parity with the Mac.

Desperate, Apple's board agreed to buy NeXT for $420 million -- its software would become the foundation of the Mac's new operating system -- and asked Jobs to return. Shortly after rejoining the company, Jobs spoke to Apple employees about restoring the company's tarnished brand.

"The way to do that is not to talk about speeds and feeds," he said at the time. "It's not to talk about why we're better than Windows.... Our customers want to know, who is Apple? What is it that we stand for? ... And what we're about isn't making boxes for people to get their jobs done, although we do that well. Apple is about something more than that.... We believe that people with passion can change the world for the better." Then he announced the Think Different campaign and its first salvo, a tribute to the people who change the world. Apple was about to turn the world upside down again. And again. And again.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

Partner in design

During Jobs's absence, Apple had hired Jonathan Ive, a brilliant industrial designer from England. Usually working in a black t-shirt and jeans, he exhibited the same obsession for perfection that Jobs had. When studying design, he built 100 models for his final project instead of the typical half a dozen. Ive had toiled in obscurity until Jobs saw his work and put him in charge of industrial design at Apple.

"Everyone says, 'I want to make a great product,' or 'I want to make a great movie,' or whatever they're doing, so there's no difference there," Jobs would say later. "There's a big difference in the outcomes." The first project that Ive and his team completed would make computers transparent to consumers -- literally.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

Behold the iMac

For almost 20 years, most personal computers had had the same boring, boxy appearance. That changed with the iMac in 1998, the first project for Ive and his group. The iMac, with its tinted and yet translucent body, threw out every computer design convention. It was undoubtedly eye candy -- the computer re-envisioned as a gumdrop. More than 2 million sold in the first year. Apple was back, and Jobs and the iMac made the cover of Time.

"We're willing to throw something away because it's not great and try again when all of the pressures of commerce are at your back saying, 'No, you can't do that,' " Jobs later said.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

A store of their own

Apple struggled with its presence in retail stores. Products were buried in a wasteland of personal computers, with clerks who didn't care if someone bought a Mac or a Windows PC. "Buying a car is no longer the worst purchasing experience," Jobs said. "Buying a computer is now No. 1."

Jobs decided that his company needed its own retail chain, locations that would promote Apple's brand and let the products seduce future customers. The stores were spacious to mirror the size of the corporate brand and to provide an uncluttered experience. Although some observers thought the move was smart, popular wisdom said that Jobs had "two years before they're turning out the lights on a very painful and expensive mistake," as one retail expert put it.

So much for popular wisdom. Apple stores have become the single most financially successful retail operation on the planet, putting even luxury goods and name-brand jewelry stores to shame. But you can understand why so many people wrote off the strategy. The numbers didn't seem to add up. How would a store sell enough computers when Apple's market share had dropped so low? Jobs was about to unwrap his answer.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

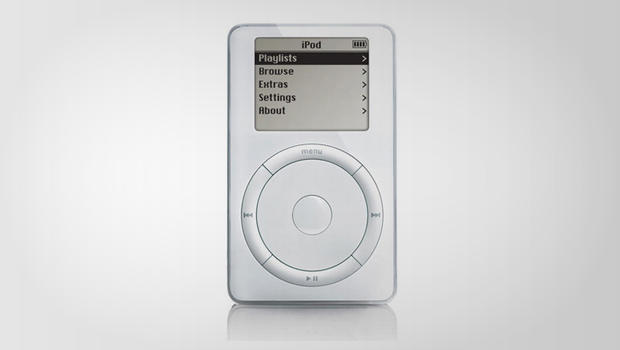

The music man

Jobs wanted to drive up Mac sales by making the device a digital hub for everything else a consumer might want to do, and music was a natural place to start. People traded digital music on services like Napster, but MP3 players were clunky and unpopular. The space was ripe for innovation.

So Apple licensed music player software and then had a top programmer turn it into iTunes, which Jobs introduced in January 2001. Then a team headed by NeXT alumnus Jon Rubinstein pulled together internal and external resources to create the iPod, which Jobs wanted in stores by the fall. He insisted on effortless integration between the iPod and iTunes, which was the magic of the system. The result: Within a few years, Apple owned the portable digital music player market.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

Tunes on the Internet

The iPod, however, would have been nothing without anything (legal) to play on it. On that front, Jobs found a promising but reluctant partner in the music industry, which was frightened out of its wits by online file-sharing and falling album sales.

Jobs wanted an online store so customers could get songs for their iPods easily and cheaply. But music labels were scared that selling single cuts for 99 cents, rather than albums for 10 to 15 times as much, would amount to financial ruin. So Jobs pointed out that iPods had to be used with Macs, which had far less than 10 percent market share. There would be 200,000 tracks. How big could it get?

Ahem. A week after the iTunes Store opened, customers had already bought a million songs. Six months later, the labels let Jobs sell to Windows users as well. Apple had transformed how people bought music.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

An echo of mortality

The iPod and iTunes were major successes. But for Jobs, that faded in importance when he was diagnosed with a rare type of pancreatic tumor. He would spend the next nine months in treatment, followed by surgery in July 2004.

True to form, Jobs was as secretive about his personal affairs as he'd long been about business. After consulting with lawyers, the company decided not to release any information to investors. Almost no one knew he had cancer until he disclosed it in an email in August of that year to Apple employees as he was starting his recuperation. Many corporate governance experts criticized the decision.

Jobs was lucky in a sense -- his condition was one of the most treatable types of pancreatic cancer, which generally kills patients quickly. He expected to return to work in September, but wouldn't appear publicly until October. Behind the scenes, another revolution was simmering. Jobs was about to turn the mobile-phone industry upside down.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

It's for you, Steve

With the iPod, Apple was already turning itself into a consumer products and services company. Why not build a phone? In 2004, Apple partnered with Motorola to bring iTunes software and music to mobile phones. Over the next two years, trademark and patent applications suggested Apple would release its own device -- and that it would be called the iPhone.

In January 2007, Jobs announced the iPhone at the MacWorld conference. It made phone calls, sure, but it was also a real computer that could run software and surf the Web. A touch-screen interface eliminated the tiny and confusing buttons typical of wireless phones and set a new industry standard.

Jobs would also upend the balance of power between handset manufacturers and wireless carriers. Apple would control the design, not AT&T, meaning that for the first time, a phone would sell a carrier. The iPhone turned into the profit engine that ran Apple. On the same day as the iPhone announcement, Apple would drop the "computer" from its name and become Apple Inc., cementing its new status as a consumer powerhouse.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

Many apps to rule them all

The iPhone was neither the first handheld computer nor the first cellphone that could run programs, but it was the first that made it easy for people to find and use the programs they wanted, creating a vibrant new computing ecosystem in the process. Where the slow, stodgy cellphone carriers had previously limited users to a fixed set of often balky programs, Apple let the world's programmers create native applications for the iPhone. Jobs bypassed the carriers and let developers sell through Apple, keeping 70 percent of the purchase price, a far larger share than possible through wholesalers and retail stores.

The move created a new dynamic. Small companies and individuals could write apps and sell them for pennies -- literally -- in hopes that volume would make them some real money. Consumers could buy apps, or download free ones, on a whim. Only a few of the hundreds of thousands of apps Apple would sell ever made serious money, but thousands of software developers wanted to take their shot at making their fortunes. It was the American dream, blown up to a global scale.

It was also controversial, because developers could only sell their software through Apple. Jobs had finally created something no one in consumer electronics had previously managed: a complete ecosystem, with control over hardware design and distribution of third-party software and content. Apple could create as close to the perfect user experience as was possible, something that Jobs had wanted for 30 years. But there were still some things he couldn't control.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

Return of a foe

Jobs fell ill again and took a medical leave in 2009 to deal with a "hormonal imbalance," according to Apple. In truth, his liver was failing and his life was in danger. So Jobs had a secret liver transplant in Tennessee.

When the news finally came out, two months after the operation, the criticism was intense. Jobs had managed to get a donor liver in three months -- roughly three times faster than the average transplantee. Many investors were also angry that Apple had failed to disclose that Jobs, the single most important man at the company, faced a life-threatening condition.

But Jobs had never been cowed by disease, and he refused to be deterred by words. There was still work to do.

Photo by Getty Images

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

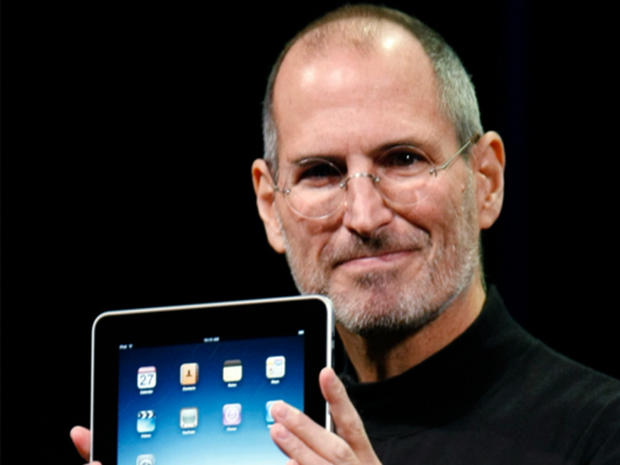

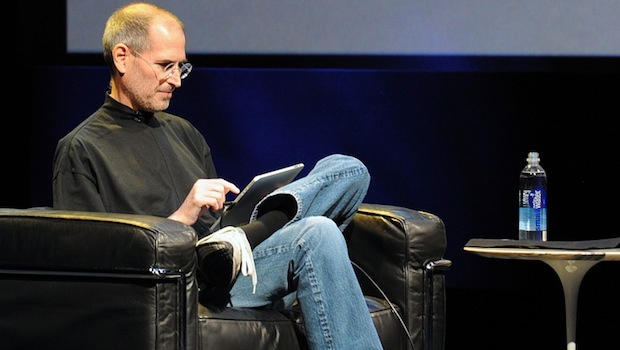

A computer for the rest of us

Jobs famously disdained market research. How could anyone know what features they'd want in a product they'd never seen before? And that's what the iPad was.

Not that the idea of tablet computers was new. But combining the iPhone's touch interface with a larger screen, the iPad gave consumers what they wanted: the ability to watch videos, surf the Web, read books and periodicals, listen to music -- all for hours on a single battery charge. Doubters, including some of the Mac Faithful, dismissed the concept. It wasn't a "real" computer. But Jobs knew what most people really wanted, and the doubters had to get in line.

Announced in January 2010 and first shipped on April 3, the iPad became the most quickly adopted computer in history. The next month, Apple's market valuation finally surpassed that of its long-time rival and partner, Microsoft. The people had spoken, and Jobs had won.

Steve Jobs and Apple: A life

The consummate rebel, triumphant

Steven Paul Jobs: Driven. Perfectionist. Arrogant. Visionary. Genius. Complicated.

- Steve Jobs in his own words: A video retrospective

- Jobs leaves as Apple CEO -- and takes the magic with him

- Apple's evolution: How 30 years of advertising hinged on 12 key moments

Love him or hate him, no one can deny that Jobs changed the world. Perhaps the most fitting words come from an Apple ad that ran shortly after his return to save the company:

"Here's to the crazy ones. The misfits. Rebels. Troublemakers. Round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently. They're not fond of rules, and they have no respect for the status quo. You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them. About the only thing you can't do is ignore them. Because they change things. They push the human race forward. And while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do."