How a U.S. "border tax" could hit your wallet

A number of companies are warming up to President Donald Trump's proposal of a 20 percent border tax, which he claims is going to spur companies to build items in America and hire U.S. workers. The proposal has pitted consumer-facing companies like Target (TGT), Walmart (WMT) and Best Buy (BBY) -- and more than 100 others -- against domestic heavyweights like Boeing (BA), Caterpillar (CAT), Honeywell (HON) and Raytheon (RTN), which make a substantial portion of their profits through exporting.

If the tax passes, companies that rely on imports will have to either try to save money by moving production into the U.S. as much as they can or by passing on the tax to consumers in the form of higher prices. The first option would take quite some time to put in effect, while the second would take only days. (Companies could also choose to eat the higher costs and reduce their profits, but it remains to be seen how many will take that option.)

Read on to see the top imports that Americans have come to depend on, and how hiking their costs would affect shoppers.

Cars and car parts

Cars and car parts make up the biggest category of U.S. imports, accounting for $280 billion in imports in 2015, according to UN Comtrade, which tracks trade flows.

While the president has accused automakers of shipping Mexico-built cars tax-free to the U.S., the reality is more complicated. "It's not like [an] entire car is produced in Mexico. Little pieces of it are produced all over the continent," said Hoyt Bleakley, associate professor of economics at the University of Michigan.

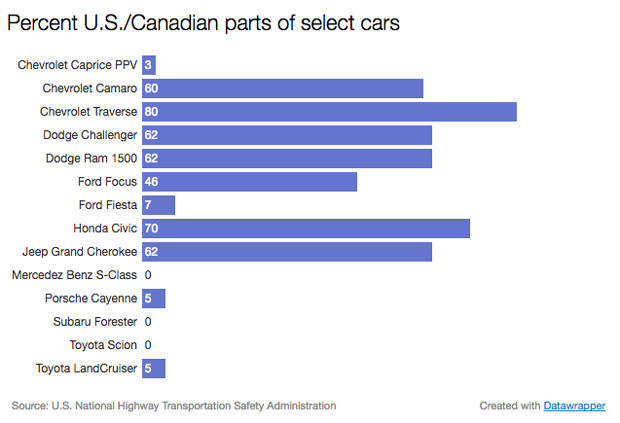

This is especially true for manufacturers like GM (GM) and Chrysler (FCAU), which rely more heavily on parts from Mexico. The best-selling truck in the U.S., Ford's (F) F-series, has 70 percent U.S. or Canadian parts. The Chevrolet Caprice -- a model popular as a police car -- has only 3 percent.

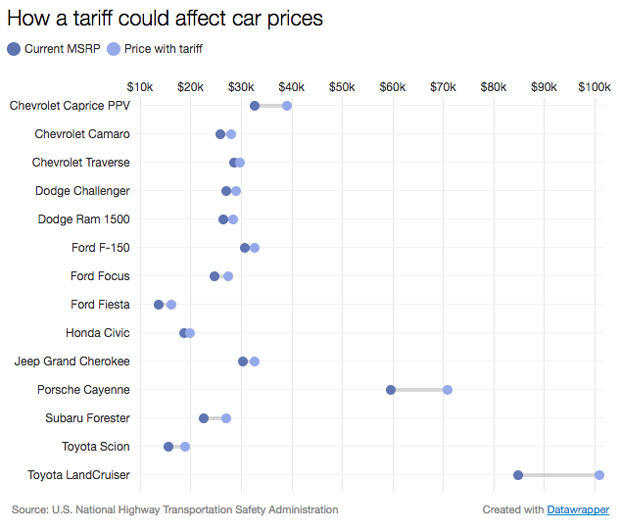

A 20 percent tariff would make some popular models more expensive by at least a few thousand dollars. The cost of luxury brands, like the Toyota Land Cruiser, would reach into the six figures. The chart below assumes a 20 percent markup on the portion of a car's MSRP equivalent to the portion of it made outside the U.S.

But a tariff would do more than make cars more expensive. The North American Free Trade agreement created "basically one big supply chain for a large number of American industries," Bleakley said. That means car parts, not just cars, are manufactured where it's cheapest for the company, considering labor costs, taxes, regulations and other factors. A border tax would disrupt the supply chain and potentially create backlogs and delays while companies consider relocating from where they've been used to working to where it's now cheaper to do so.

Gas

Oil and petroleum products have been the second-largest U.S. import for years, coming to $186 billion in 2015, according to UN Comtrade. They come overwhelmingly from Canada, followed by Saudi Arabia, Venezuela and Mexico.

"What we've been doing historically is importing a lot of crude [oil] and essentially refining it. If you impose a tariff, the import costs for refineries are going to jump 20 percent," said Gregory Daco, chief U.S. economist with Oxford Economics. "Given that gas prices are quite low, they would likely pass that on to consumers," he added.

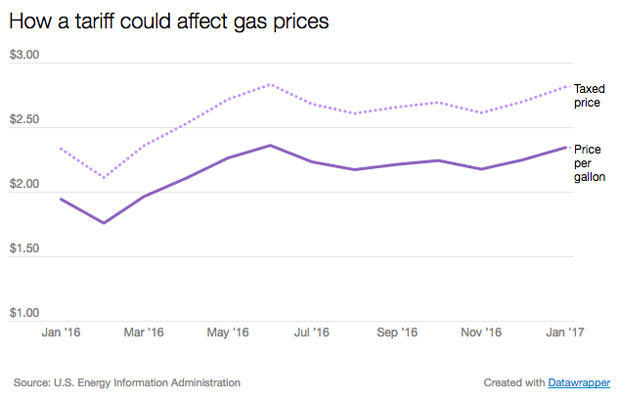

Here's how gas prices would have looked over the past year with a 20 percent tariff in place.

Higher gasoline prices directly influence U.S. inflation -- they were a major reason for the consumer price bump in January, the highest one-month increase in the U.S. for four years. And they also have an indirect effect on other prices. "A lot of the goods we consume have an indirect fuel component cost," Daco said. In other words, if it costs more to deliver tomatoes to your local grocery store, you'll wind up paying more for them.

Consumer electronics

Some of Americans' favorite gadgets come from abroad, including the coveted iPhone, which Apple (AAPL) manufactures in China, and the Samsung Galaxy series, which is made in Korea. Retail prices for those, outside of a contract, run $500 or more. Still, a 20 percent tariff likely wouldn't apply to the sticker price of a new gadget.

Analysts put the cost to manufacture a new iPhone 7 at $225, while a Samsung Galaxy S7 costs about $255. That would increase their sticker prices by $45 and $51, respectively. Apple and Samsung could also choose to make a smaller profit on each unit if it looks likely that a higher price would lead to fewer purchases.

Nonetheless, Daco said, the U.S. imports a lot of electronics. "If [a tax] is pushed forward, there's likely to be tremendous opposition from the retail industries," he said.

Groceries and restaurant meals

Despite the increasing globalization of agriculture, it's not often that food makes it onto a "top imports" list. That's partly because of cost -- it would take a lot of tomatoes to come close to the import value of a car engine -- and partly because a lot of U.S. policies still give preference to farmers and agribusiness at home.

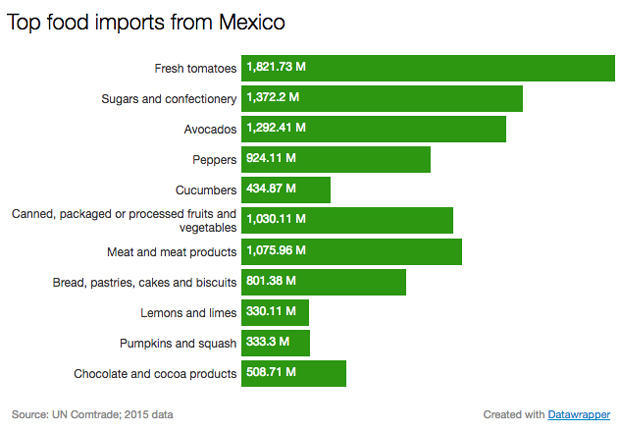

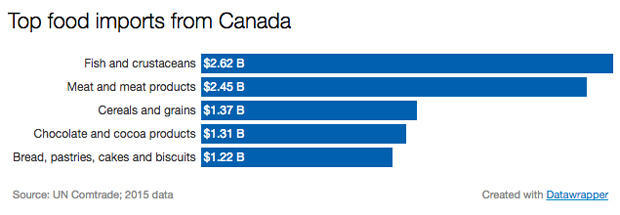

Still, the U.S. imports a fair amount of food from its neighbors Mexico and Canada, including $1.8 billion worth of Mexican tomatoes and $1.3 billion worth of avocados. Americans also eat a large amount of meat from both countries.

In relative terms, Americans spend a smaller percentage of their income on food than any other country. But consumers who've come to expect a low grocery bill are unlikely to take kindly to increases. Last year's avocado shortage brought prices up to $3 apiece for a large avocado in some places. (And many restaurants, unwilling to deal with the high cost, stopped offering them for a short time.)

A border tariff wouldn't cause the price to rise so dramatically, but 20 percent above typical costs could have consumers paying $2 per avocado, or $3.60 a pound for organic tomatoes (on sale!) or $5 a pound for ground beef.

If the U.S. tariffs were to equally apply to our northern neighbor, a packet of smoked Canadian salmon could run consumers $30 a pound.

It's likely some multinational corporations will be able to shift production to the U.S., but many products U.S. consumers have come to expect simply grow better across the border. "There's just less stuff that can be grown here as effectively as in Mexico," said the University of Michigan's Bleakley. "The best substitute we have for Mexican dirt is dirt in California, and that's going to be tough to scale up if California continues with its water crisis."

Not to mention that the costs of U.S. labor could increase food prices even beyond what a border tax would, if President Trump carries through his promise of deporting large numbers of undocumented immigrants.