Some California buildings share a flaw with the ones that fell like "pancakes" in Turkey quake, but similar devastation is unlikely

Thousands of buildings in California share a flaw with the structures that collapsed in Turkey and Syria earlier in February, but experts say it's unlikely that a similar crisis could take place in the United States.

On Feb. 6, Turkey and Syria were struck by two 7.8 and 7.5 scale earthquakes, with further aftershocks only leading to more chaos. Millions of people have been displaced and tens of thousands have died, with rescue crews working around the clock to pull survivors from the rubble. One of the main reasons that the buildings collapsed like "pancakes" is the widespread use of non-ductile concrete, a building material that does not have much steel reinforcement and holds up poorly in earthquake conditions. Ductile concrete is more reinforced and can undergo more severe conditions before breaking.

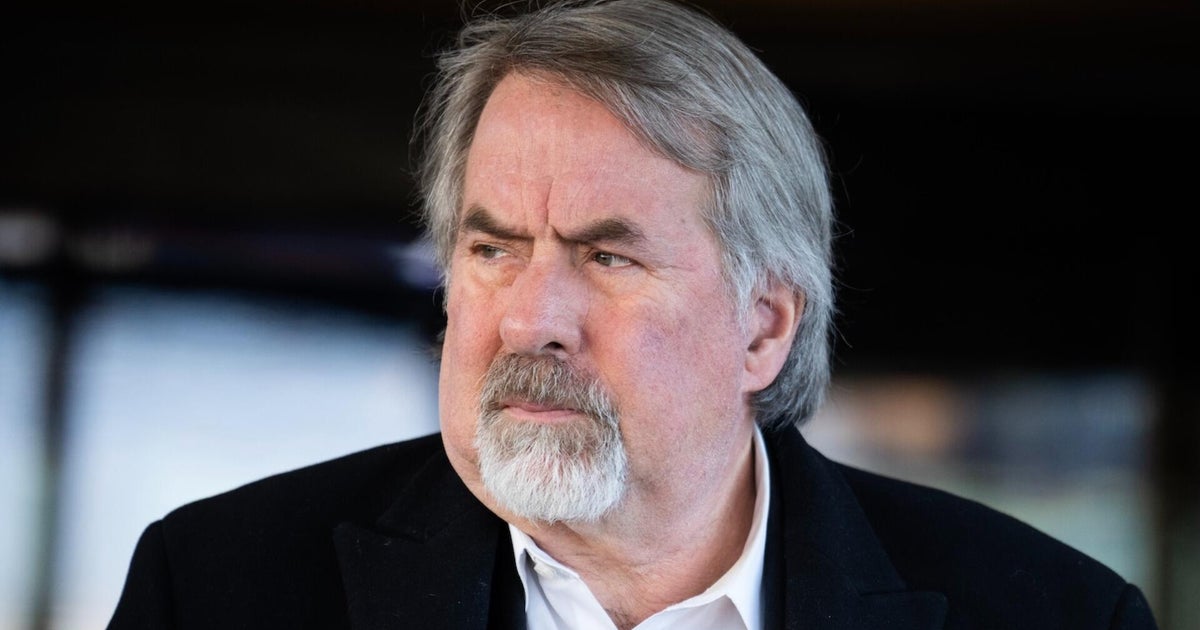

Terrence Paret, a senior engineer who studies seismic retrofitting and has done seismic risk assessments in Turkey said the presence of this much non-ductile concrete is why there are "seismic tragedies every decade" or so in Turkey. While the thousands of non-ductile concrete buildings in California are alarming, they aren't nearly as common as they are in Turkey, primarily because such buildings stopped being erected in the United States after a 1971 earthquake in San Fernando.

Still, thousands of buildings in California erected before 1976, when new building codes led to stricter requirements, are built with the same material. It's hard to determine an exact number of buildings, multiple experts told CBS News, but estimates range between as few as 7,000 buildings to as many as 17,000 buildings in the highest-risk counties. Most are residential buildings, but some are schools and government buildings.

While these buildings share the same flaws as the Turkish and Syrian structures — they're brittle, and are in a part of the country prone to earthquakes and other seismic events — several "compounding factors" mean it's unlikely that a crisis of such major scale could occur on the West Coast.

One major difference is the attitude towards such construction: Cities in California are actively working to retrofit non-ductile concrete buildings. The first such ordinance was introduced in Los Angeles in 2015, and other cities, including Beverly Hills, Burbank and Santa Monica, have enacted similar ones. However, the retrofits are slow going: The Los Angeles plan is on a 25-year-timeline, and Karin Liljegren, an architect who founded Omgivning, a firm that focuses on revitalizing downtown Los Angeles and authored a white paper on non-ductile concrete retrofitting, said she thought it was unlikely that that goal would be met, despite a "real positive movement" to see change.

Another major difference is construction in the United States. Turkish buildings tend to have something called a "soft" or "weak" story as its ground floor, meaning that that floor is more flexible or weak because a door, window or other open feature is where a supporting wall would be and lacks the stability that would protect from an earthquake. This is less common in the U.S. because of building codes. Buildings with these stories in the U.S. have also been retrofitted.

"What collapsed in Turkey is almost exclusively non-ductile concrete construction," said Paret, who spent time in the country after a similarly devastating earthquake in 1999. "The buildings in that part of Turkey that collapsed are of a type that's endemic ... which is why so much of Turkey is at such high-risk. We don't have hundreds of thousands or millions of them, so the size of the problem starts out being much smaller here than there."

Even though in California, the scope of the problem is much smaller than in Turkey, one major obstacle in the retrofitting process is the cost. Liljegren said that for many, this could quickly turn into a multimillion-dollar process.

"Everyone wants to retrofit their building, but no one has four million dollars," Liljegren, the architect said.

Robert Kraus, a structural engineer, said early cost projections in Los Angeles estimated that it would cost about $150 to $200 per square foot renovated. Another issue is the invasiveness of the renovations: To retrofit non-ductile concrete, "new, stiff elements" must be placed around the older elements to limit their movement during earthquakes and reinforce them, Kraus said.

"These inherently span across most of the building area," Kraus said. "It's not like you can tuck it into a closet or sneak it in too many places. These are fairly large elements."