California Stores DNA From Every Baby: Renewed DNA Privacy Concerns Following SFPD Rape-Kit Allegations

SACRAMENTO (CBS13) — In the wake of the controversy over allegations that the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) used a victim's rape-kit DNA to later identify her as a suspect in a crime, there are renewed privacy concerns related to California's biobank, which stores DNA samples from nearly every child born in the state.

Rape kits aren't the only place where law enforcement may get access to stored DNA that wasn't intended for criminal investigations. It's a little-known fact: the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) keeps newborn blood spot (NBS) samples from every child born in the state. They are stored indefinitely in a state-run biobank and may be purchased for research or used by law enforcement without your knowledge or consent.

The DNA from the samples may be used for potentially life-saving research, but in light of growing privacy concerns related to evolving DNA technology, there are renewed questions about what else the DNA is being used for and why the state does not ask for consent before indefinitely storing a child's DNA.

ALSO READ: California Biobank Stores DNA From Every California Baby

Nearly every baby born in the U.S. gets a heel prick shortly after birth. Their newborn blood was used to fill six spots on a special card that are used to test the baby for dozens of genetic disorders that, if treated early enough, could prevent severe disabilities. The test itself is crucial and potentially lifesaving, but it's what happens after the test that has some concerned.

What Most Parents Don't Know

Most parents are shocked to learn that their child's leftover blood spots become "property of the state" and are stored indefinitely in a state-run biobank to be used for research without their knowledge or consent.

California has been storing blood spots since 1983, collecting more than 9.5 million since 2000 alone. The state can now test newborns for more than 80 genetic disorders thanks to research using the stored blood spots.

To be clear, there is no genome database. The state does not extract or sequence the DNA, though a researcher or investigator may.

Since 2014, all research requests must first be approved by the state's Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS). However, blood spots are not considered human subjects in California and therefore do not require a parent's consent before they can be stored by the government or sold to researchers.

The state has long insisted that the blood spots are de-identified before they are given to researchers, meaning they only receive the blood and a number without any identifying information.

But privacy advocates note that the state can - and does - re-identify them for law enforcement and, thanks to genetic genealogy, made famous by the Golden State Killer case, it's now common knowledge that DNA is inherently identifiable.

ALSO READ: Genetic Genealogy Used In Golden State Killer Case Opened Door For More Than 150 Cold Cases

Newborn Blood Spots Used By Law Enforcement

"DNA absolutely can be identified," said Cece Moore, a prominent genetic detective who uses genealogy DNA to help solve crimes. "I think the public has become more aware of that."

Thanks to the investigative genetic genealogy techniques that were first used to find the Golden State Killer, Moore says a large percentage of the U.S. population can now be identified using unidentified DNA and public ancestry databases.

They no longer need a close relative to identify un-identified DNA. "We just need to get a handful of second, third, fourth cousins in order to be able to reverse engineer the family tree," which Moore explained can generally be found by running the un-identified DNA through a public genetic genealogy site.

"A blood spot is actually a perfect sample to be able to use for this process" she added.

ALSO READ: DNA From Newborn Bloodspot Biobank Helped Crack 2007 Infant Death Cold Case

Records obtained by CBS13 reveal that blood spots are being used by law enforcement. We found at least five search warrants and four court orders for identified blood spots before the Golden State Killer case popularized investigative genetic genealogy.

Since then, investigators have confirmed newborn blood spots are being used to solve cold cases.

"It's definitely for the greater good," Moore pointed out.

Ethical Concerns: Parents Don't Get to Consent

While Moore relies on access to DNA, she also believes in informed consent before DNA is used for research or by law enforcement.

Moore, who has long been an expert in genetic genealogy, says she turned down requests to help law enforcement until the public genetic genealogy site they use, GEDmatch, began notifying users that law enforcement had access to their DNA.

"The vast majority of people weren't even aware that we could use genetic genealogy for law enforcement purposes until the Golden State killer suspect was arrested," she explained.

In the wake of the Golden State Killer announcement and the widespread media coverage that followed, GEDmatch added a disclaimer to the website notifying users that their DNA might be used by law enforcement.

Only then, did Moore feel it was ethical to use the DNA for purposes other than genealogy.

ALSO READ: Genetic Genealogy Used In Golden State Killer Case Opened Door For More Than 150 Cold Cases

"People have the right to choose how their DNA is used and how their children's DNA is used," Moore said.

Except, from rape kits to newborn blood spots, in California, they don't.

Unauthorized Law Enforcement Use of Stored DNA

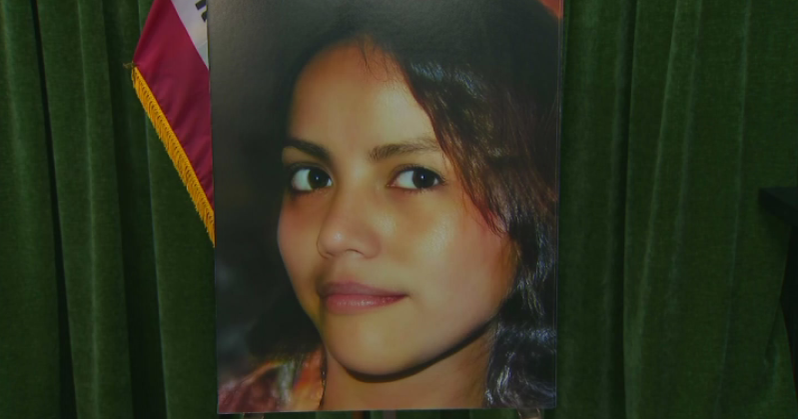

The San Francisco Police Department recently re-ignited DNA privacy concerns after the city's district attorney accused the agency of storing and using DNA that wasn't intended for criminal investigations.

The district attorney alleged the department has been entering rape-kit DNA from sexual assault victims into its criminal database and he accused SFPD of identifying a former rape victim as a suspect through her rape-kit DNA.

"It's really concerning when we hear about law enforcement getting access to this kind of data that's been collected for a non-law enforcement purpose," said Jennifer Lynch, Surveillance Litigation Director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Lynch, and others, worry that unauthorized uses of DNA could have a ripple effect, making rape victims reluctant to come forward and parents reluctant to get their child a potentially lifesaving genetic test.

"I think it's really time to revisit the pros and cons of storing this genetic information," Lynch said.

The San Francisco district attorney suggests the use of victim rape kit DNA to identify suspects is a violation of the California Constitution, which mandates the "prompt return of property when (it's) no longer needed as evidence."

But when it comes to newborn DNA, there are no laws limiting retention, or even requiring notification that the state's storing your DNA indefinitely.

California's new Genetic Information Privacy Act only applies to commercial companies, not law enforcement or the state.

"I think there definitely should be a law that parents should be informed that California is storing their baby's DNA. There's no reason to not inform parents of that," Lynch said.

She believes the state should be required to get written consent from parents before storing a child's blood spot, and she specifies that the consent should be obtained early in the pregnancy so that parents have the time to understand the information without the stress of a newborn.

"We have to give people the opportunity to consent to that. We have to trust that people, once they're informed, will make the decision that's right for them with their genetic material," Lynch said.

CDPH insists that they only provide DNA samples to law enforcement with a warrant, though Lynch notes that policy is enforced at the discretion of the current agency director. It is not required by any law and can be altered by future directors.

Most Parents Don't Know The State is Storing Blood Spots

Moore and Lynch are among many who are concerned about the way California obtains newborn DNA samples without consent. Moore noted that GEDmatch users choose to upload their DNA while most parents don't even know their child's DNA is being stored.

While parents must pay the state for their child's genetic test, the law does not require the state to get consent before storing or selling remaining blood spots to researchers.

According to the state, "[The California Department of Public Health] has never had a policy for opting out of storage before blood is collected."

"It is forever available for re-identification," Moore stressed, "and so I think that parents have the right to weigh in on that decision."

Parents can request that the state destroy the blood spots after they've been stored, but the state says it "may not be able to comply" and most parents have no idea how.

California's "Disclosure"

California law allows for the storage and use of "Newborn blood collected by the Genetic Disease Screening Program" for research purposes. CDPH told CBS13 that because there are no "timeframes or prohibitions for retention," they believe they have the right to store the blood spots indefinitely.

State regulations say that parents are supposed to get "informational material" about the genetic screening program once before their due date and again in the hospital before the heel prick test.

The "material" used to come in the form of a multi-page booklet. The information about opting out of blood spot storage was buried in a Q&A on pages 13-14.

"Are the stored blood spots used for anything else? Yes. California law requires the NBS program to use or provide newborn screening specimens for department approved studies of diseases in women and children, such as research related to identifying and preventing disease..."

Can I request that my baby's blood spots be destroyed? You may request your baby's blood spots be destroyed after newborn screening has been completed. Keep in mind that if your baby's blood spots are destroyed, they will not be available if you need them in the future. To get a form to request that your child's blood spots be destroyed, go to: www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/GDSP/Pages/ParentForms.aspx "

However, half a dozen new parents previously interviewed by CBS13 unanimously felt the language was misleading. They felt the state was trying to hide the fact that the blood spots would be stored indefinitely, that they would be available to law enforcement and that they could be purchased by private researchers.

Several years later, the booklet has now been replaced by a one-page pamphlet that makes no reference at all to storage, research, law enforcement, or opting out. There is one line at the bottom of the page stating "for information about what happens to leftover bloodspots" parents can go to the state's website.

The webpage provided contains more than 20 individual links to additional information regarding various aspects of the program. However, nowhere on the page does it indicate the child's blood spots will be stored and may be used for research or by law enforcement without consent.

That one-page pamphlet is just one in a stack of documents that new parents are given when they bring their newborn home from the hospital.

How To Find The Storage/Opt-Out Information

CDPH said the old booklet is still available online and the department has produced a new informational video for parents, though it's not clear how most parents would find the links.

CDPH also states "The NBS Test Request Form (TRF) has information about storage and use of residual blood spots, and parents are provided with (that) part of the form."

However, the request form is generally filled out by the nurse and the parents aren't asked to sign it. A copy of the form is supposed to be included among the stack of other pamphlets and forms that parents leave the hospital with.

The Consent Debate

In 2014, a federal law temporarily classified blood spots as human subjects, meaning some researchers would need to get informed consent to use them. However, the law only applied to federally funded research - not private research - and the protection was removed last year.

Studies find "states that retain (blood spots) may be acting outside the scope of their legal authority," and several states have been successfully sued by parents. The state's untimely had to destroy all samples taken without consent.

The ACLU believes "that parents have the right to know before the state stores their child's blood and allows it to be used by researchers and others." However, many in the research community do not.

Those opposed to informed consent say it may increase the number of people who opt-out of storage and thereby reduce the number of specimens available for life-saving research.

Others oppose consent arguing that parents might be more likely to opt-out of the life-saving genetic test if given the opportunity to opt-out of storage after the test.

However, privacy advocates like Moore and Lynch believe the appearance of secrecy may have that effect on its own as the public becomes more aware of the many uses for de-identified DNA.

"If we lose the trust, if we use their DNA in ways they haven't consented to, I'm concerned that people will stop testing completely," Moore said.