Forensic Genealogy Used In Glen McCurley Case Could Help Close Thousands Of Unsolved Murders

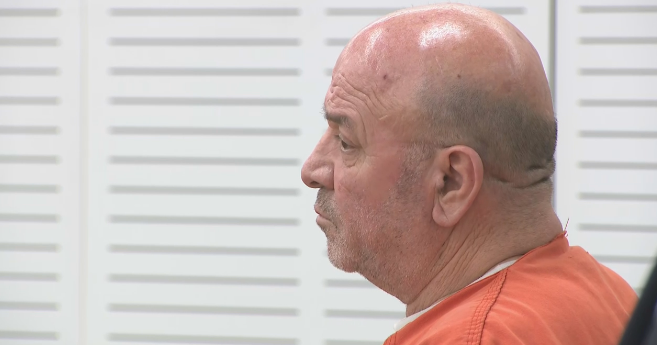

FORT WORTH (CBSDFW.COM) - When cold case investigators told Glen McCurley last year they knew he was the person who killed Carla Walker in 1974, he challenged them.

If they knew, then why didn't anyone come get him back then?

Back then, they didn't know, Fort Worth detective Leah Wagner told him.

"But we do," she said. "Because we have evidence."

McCurley's guilty plea Tuesday, August 24, to kidnapping and killing Walker is believed to be a groundbreaking outcome, according to detectives, prosecutors and geneticists who worked on the case.

They believe it is the first time forensic genealogy has been presented as evidence in a criminal trial, resulting in a conviction.

The outcome could encourage the funding and use of the testing in other criminal cases, and possibly close some of the more than 250,000 unsolved murders across the country.

"This is a glimpse of the future," said David Mittelman, the founder and CEO of Othram which gave detectives the lead last year that led to McCurley.

The lab in The Woodlands, north of Houston, was built from scratch with an outcome like this in mind. Working only with law enforcement, Othram's methods access potentially hundreds of thousands of markers in DNA, rather than just a few dozen. It can also tune out contamination that clouds DNA using conventional methods.

Then they begin to find matches contained in genealogical databases. It often turns up distant relatives to start, which are then narrowed down to someone close. In McCurley's case, they found matches with a second or third cousin, and other family who had lived in Denton County.

Othram's methods have helped identify a man whose body was at the bottom of a lake for five years.

There was a murder suspect in Montana.

A hiker found dead in Florida.

It's been proven successful, but that doesn't mean it comes cheap.

In the McCurley trial, testimony revealed initial DNA testing starting at the Serological Research Institute in California rang up a bill of at least $18,000.

Police departments looking at hundreds, if not thousands of cold cases, simply don't have the budget to test evidence in each instance.

"I do think funding is a barrier," Mittelman said. "It's not a tech barrier, it's a funding barrier. And I think some of this will be eased by this outcome in court."

Seeing the science stand up in court though, questioned by defense attorneys, and resulting in a guilty plea, strengthens the argument for investigators pushing for money from a tight department budget.

Kim D'Avignon, who prosecuted the McCurley case for the Tarrant County District Attorney's office along with Emily Dixon, agreed it could be groundbreaking.

"There are boxes and boxes and boxes of cases, that we don't have the money to test for," she said. "And that's one jurisdiction. That's Fort Worth. Every jurisdiction across the United States has that same problem."

Beyond just solving a mystery, Mittelman said it meant the world to him to see Walkers family, be able to directly address a person in court who they had been searching for all this time.

He's all in, he said, to see more cases close the same way.