Native American storyteller invites people to "rethink" the myths around Thanksgiving

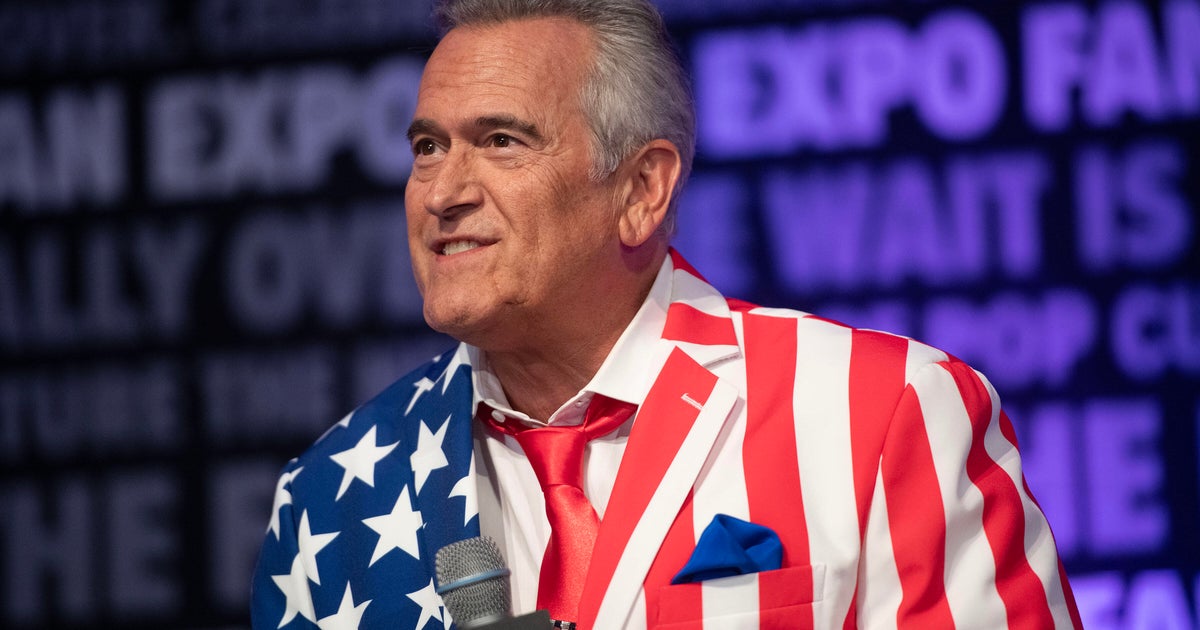

Native American storyteller Perry Ground, a Turtle Clan member of the Onondaga Nation, starts his "rethinking" of Thanksgiving with a quiz.

Ground, who has been telling stories for 25 years in an effort to increase cultural understanding around Native American history, says his audience is usually surprised by "what they think they know – and don't know– about the story of the 'First Thanksgiving.'"

The three-day feast in 1621 was a moment in time, with just one tribe, Ground says, but has shaped the way that many people think about Native Americans because of the role they are believed to have played in the event.

Ground hopes his work – and those of other native voices – can help Americans "rethink" the idea of Thanksgiving by providing a more nuanced understanding of what happened in 1621 and the incredible destruction and upheaval forced upon native tribes when settlers arrived in North America.

The 21-question quiz includes questions on whether turkey was served at the "First Thanksgiving" feast, why the celebration became a national holiday and what the interaction was really like between the Pilgrims and Native Americans.

Many respondents don't know the answers. They also don't realize how little Native Americans had to do with the "creation of Thanksgiving," said Ground. He tries to widen their perspective by sharing the history and dispelling the myths surrounding the holiday through story.

In 1621, Pilgrims shared a feast with the Wampanoag people, which was recounted in a letter written by settler Edward Winslow. He wrote, "we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted."

From those few lines rose the myth surrounding the relationship between Native Americans and settlers. The interaction was presented as a rosy story instead of talking about the outcome and the effects on the native community, said Joshua Arce, president of Partnership With Native Americans, one of the largest Native-led nonprofits in the U.S.

Arce, a member of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, said Thanksgiving for many Native Americans is "a day of resilience, of mourning – and a day of survival."

Cooperation and peace between the native tribes and the settlers after the feast was short-lived. Throughout the period of European colonization, millions of Native Americans were killed, either in fighting or by disease. Between 80% and 95% of the Native American population died within the first 100-150 years of European contact with the Americas, researchers estimate.

It was after "The Trail of Tears," when Native Americans were forcibly displaced from their homelands following the 1830 Indian Removal Act (with over 10,000 dying on the brutal trek) that Thanksgiving became a holiday. President Abraham Lincoln made a proclamation in 1863 that Thanksgiving was to be regularly commemorated each year on the last Thursday of November. On Dec. 26, 1941, President Franklin D.

Roosevelt signed a resolution establishing the fourth Thursday in November as the federal Thanksgiving Day holiday.

Arce said the struggle for the native community is to "reconcile what happened then to now." November is a time of harvest and part of the natural cycle when communities prepare for winter. For Arce, incorporating seasonal elements important to native communities and their distinct traditions into Thanksgiving can help honor their survival and resilience.

For Ground, storytelling is the way to learn about Native American cultures and traditions, and he wants his audience to engage through different techniques, like his quiz.

In addition to his "Rethinking Thanksgiving" presentation, he also tells stories about different Native American myths and legends, because while communities have evolved, "we also have these traditions and ideas that are important to us."

For Ground, Thanksgiving shouldn't be the only time people should think about Native Americans. "We are human beings that have a continuum of history and we continue to exist today," he said.