Study: 'Meaningful improvements' Using Gene Therapy in Parkinson's Disease

A first-of-its-kind study of gene therapy in the treatment of Parkinson's disease determined that half of all patients who received the treatment had "clinically meaningful improvements" of their symptoms within six months of surgery.

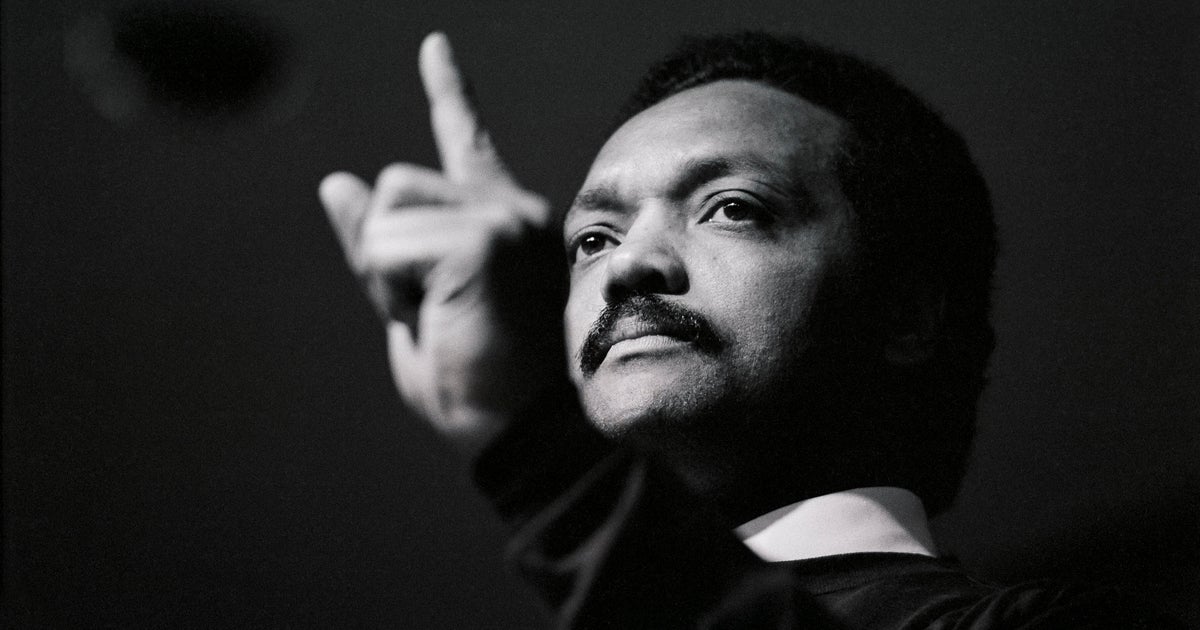

"The study demonstrates that the promise of gene therapy for neurodegenerative disorders has become a reality," says study lead author and co-principal investigator Peter LeWitt, M.D., director of movement disorders at Henry Ford Health System.

The new study is a fast-track publication in the current issue of The Lancet Neurology.

That "promise," if verified by currently ongoing follow-up studies and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, could vastly improve the lives of many of the one million Americans who now suffer the debilitating effects of Parkinson's disease.

Parkinson's disease, which usually affects people over age 50, is a progressive disorder that gradually deteriorates nerve cells in the brain. As the disorder worsens, its effects are visible in the abnormal body movements of its sufferers. These include tremors and stiffness in the arms, legs and neck; slowness of movement and coordination; and trouble with walking and balance. Dementia can develop in the late stages of the disease.

The Michigan Parkinson Foundation estimates that as many as 60,000 new cases are diagnosed each year in the U.S.

The new study, which used double-blind sham surgery controls, tested the effectiveness of a gene therapy known as NLX-P101 in 45 subjects with moderate to advanced Parkinson's disease. The patients, ages 30 to 70, were chosen because their symptoms didn't respond well to other treatments.

Among the study group, each patient was randomly selected to receive either NLX-P101 therapy or sham surgery. All of the procedures were done with local anesthesia, and most of the patients were released within 48 hours after surgery.

Sham surgery is a controversial, but generally an accepted technique to mimic a brain operation. Its intent is similar to that of a placebo in studying the effects of test drugs and, in this case, it added to the scientific conclusiveness of the study.

For Parkinson's disease, most research and treatment to date has focused on decreased dopamine levels in the brain. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that is integral in controlling movement, learning and mood. Standard treatment has often included the use of levodopa, a drug that stimulates the production of dopamine, but which causes adverse reactions and complications in many patients.

The gene therapy approach in the current study acts on an alternative neurotransmitter system of the brain involving a signaling chemical called GABA. Another treatment involves permanently implanting a medical nerve-control device in the brain called deep brain stimulation.

The gene therapy study with NLX-P101 "met its primary outcome measurement and demonstrated that NLX-P101 gene therapy was safe and well-tolerated over the six-month blinded study period." In contrast to the concept of implanting stem cells for treating Parkinson's disease (which has never been tried), gene therapy has been widely used in laboratory research and already is undergoing human testing for other disorders. The procedure does not require general anesthesia, which has potential complications, or implantation of a medical device.

"Subjects in our study who received the NLX-P101 treatment displayed better motor performance and control of Parkinsonism than subjects who received sham surgery," LeWitt said. "This benefit occurred early and was long-lasting."

LeWitt was joined in the experimental trial by Henry Ford neurosurgeon Jason Schwalb, who heads the functional neurosurgery movement disorders program.

The therapy was developed by Neurologix Inc., a New Jersey-based biotechnology company that specializes in finding, developing, and commercializing gene therapies for serious brain and nervous system disorders.

The company funded this study, which included Henry Ford among seven research centers nationwide.

More at www.henryford.com.