Joe Paterno, Marvin Miller Mark 2012 Sports Deaths

By Fred Lief, AP Sports Writer

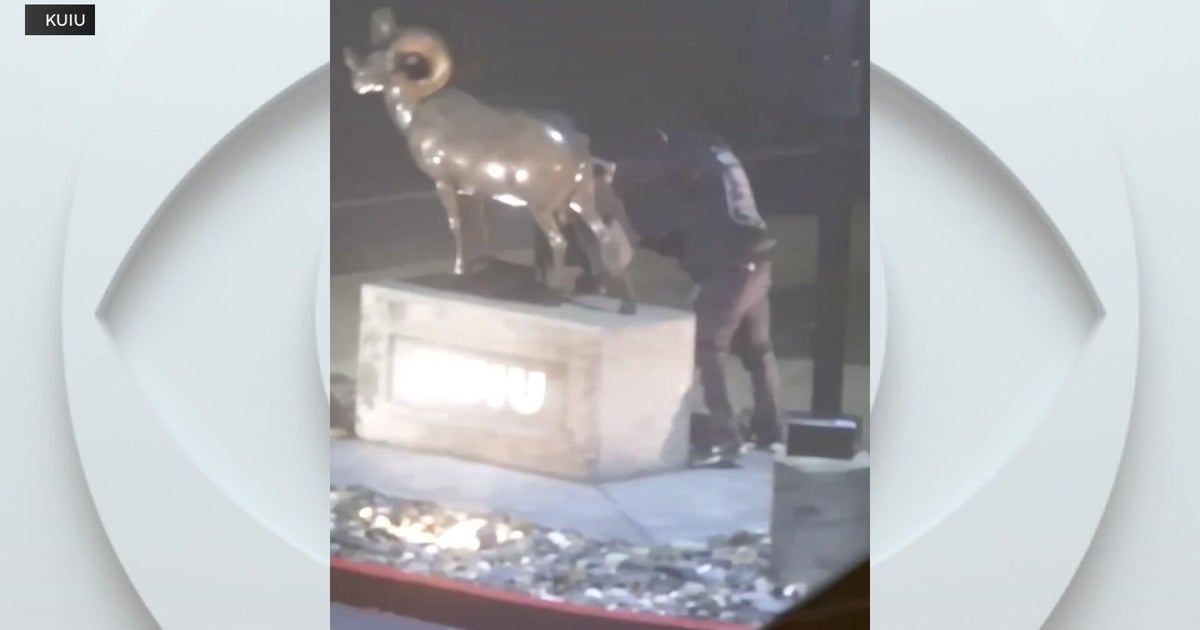

He went to work where a statue of him stood outside the stadium, his place of business for more than a half century. He would not live to see the statue hauled away.

The other never had a statue erected in his honor, although some said there should be one, bronze or otherwise, at the doorstep of the Baseball Hall of Fame. He would live to see himself spurned by the Hall five times.

Joe Paterno and Marvin Miller, a couple of New Yorkers, were bookends to the year's losses in sports - the football coach dying at 85 in January, the union leader at 95 a few days shy of December.

The year's obituaries in sports also came with a tragic soundtrack of gunfire: Junior Seau, Hector Camacho, Jovan Belcher. More quietly, baseball now moves on without Gary Carter and basketball without Jack Twyman and Rick Majerus. Big names in boxing like Angelo Dundee and Carmen Basilio also were lost.

Paterno's legacy was a complicated mix of football and education, universities and leadership, responsibility and justice. Miller was an often unspoken part of a running conversation about the culture of money of sports, and the rights of the people who play the games.

Paterno's death came less than three months after it was disclosed he had lung cancer. That news fell on a State College, Pa., community already shocked by the child sex-abuse revelations regarding longtime assistant coach Jerry Sandusky.

Paterno's death closed a sweeping narrative, although the legal fallout and emotional wreckage are still very much alive. The swiftness of it all was almost Shakespearean in scope: the fall of a man who for so long was the symbol of everything right in his work only to be undone by scandal and cast aside.

In his blue windbreaker and black-rimmed glasses and his words still carrying echoes of Brooklyn, Paterno was the face and foundation of Penn State. He raised many millions of dollars for the school. His was the voice of perspective and reason in college sports. He won more games than anyone else, until the NCAA over the summer vacated victories dating to 1998. Legions of Penn State players - and countless others in State College - swore by the man. He been on the coaching staff for more than 60 years, and had been the head coach since 1966. He was JoePa.

But then came the startling accusations and subsequent conviction, after Paterno's death, of Sandusky. Paterno insisted he followed the chain of command, informing his athletic director of what he was told had happened, although he did not go to the police.

Paterno said he was not given a graphic account of Sandusky's locker-room rape of a young boy. Later, with the Washington Post in his last interview, he acknowledged a naivete - "I never heard of ... rape and a man."

Paterno's remorse had already been clear by then. Hours before Penn State trustees fired him, he said: "This is a tragedy. It is one of the great sorrows of my life. With the benefit of hindsight, I wish I had done more."

Miller sent a bulldozer through the landscape of Major League Baseball, and by the time he was done the terrain of all professional sports would never look the same.

Miller, with silver hair and mustache, cut his union teeth with the steelworkers. Surely one of his biggest triumphs was getting players to think of themselves as an organized work force with rights, not hired hands serving at the whim of ownership.

"He changed not just the sport but the business of the sport permanently," former baseball Commissioner Fay Vincent said. "And he truly emancipated the baseball player - and in the process all professional athletes."

Miller ran the union from 1966 to 1981. He clashed with owners and commissioners who were wary of him every step of the way. When he started, the minimum salary was $6,000; this past season, the minimum was $480,000. When he took over, baseball was still a decade away from its first million-dollar player; today, the average salary is $3.2 million.

And it was not only the players who grew rich as the game became more popular than ever. The very owners who fought Miller watched the value of their franchises soar to fabulous sums.

The springboard was free agency and the end of the reserve clause that bound player to club. The landmark decision came in 1975 when arbitrator Peter Seitz sided with the players. Seitz later would refer to Miller as baseball's Moses.

"Anyone who's ever played modern professional sports owes a debt of gratitude to Marvin Miller," Dodgers pitcher Chris Capuano said. "He gave us ownership of the game we play."

Gun violence cut across sports this year.

Seau, the one-time fierce linebacker of his hometown San Diego Chargers, shot himself in the chest at 43, leaving no note and so many in football shaken. Camacho, the loud, boastful fighter and a champion several times, was shot in the face while in a car in Puerto Rico. The coffin of the 50-year-old boxer was carried from a New York church to shouts of "Macho." Belcher of the Kansas City Chiefs shot his girlfriend to death. The 25-year-old linebacker then drove to the Arrowhead Stadium parking lot, thanked his coach and general manager who were there and put a bullet in his head.

"This is such an unexplainable event," Chiefs teammate Andy Studebaker said.

Camacho's death was one of so many in boxing. The lineup could fill a wing of its Hall of Fame:

Dundee, the peerless trainer who was in the corner for Muhammad Ali and Sugar Ray Leonard and always drew the best out of his fighters, was 90. He also handled Basilio, who died at 85 after a career in which he took the middleweight crown from Sugar Ray Robinson in 1957 only to lose it six months later.

Former heavyweight champ Michael Dokes, with a long string of victories and a long rap sheet, was 54; Teofilo Stevenson, the three-time Olympic champion from Cuba with a thunderbolt for a right hand, was 60; Emanuel Steward, who ran the famed Kronk Gym in Detroit and trained Thomas Hearns and Lennox Lewis, was 68; and boxing historian Bert Sugar, the raconteur with the fedora and cigar who knew everybody and everything in his sport, was 75.

Baseball became a little less joyful without Carter, "The Kid" gone at 57 from a brain tumor. A Hall of Fame catcher mostly with the Mets and Expos, Carter was a commander behind the plate who never lost sight of what a pleasure it was to play the game. Johnny Pesky, a lifetime .307 hitter and part of the Boston Red Sox's DNA, died at 92, but Pesky's Pole in right field in Fenway Park remains in play.

Lee MacPhail, the longtime executive who ruled in the George Brett Pine Tar case, died at 95, the oldest-living member of the Baseball Hall of Fame. Bill "Moose" Skowron, the sturdy first baseman for the great Yankee teams of the 1950s and `60s, was 81. Pedro Bourbon, 65, was a reliever who helped the Reds win two straight World Series in the 1970s; Eddie Yost, a third baseman who made a fine art of drawing walks, was 86. Also leaving the game were two men who saw a lot of balls and strikes - umpires Marty Springstead and Harry Wendelstedt.

Basketball is poorer for Twyman's death at 78. He was a critical piece of the Cincinnati Royals, and in 1960 averaged more than 31 points. But that was only part of it. When Maurice Stokes smacked his head on the court in 1958 and was soon paralyzed, it was Twyman who became his legal guardian, helped foot the bills, organized an exhibition game in his teammate's name and was there for Stokes until the end.

"That's what friends are for," Twyman said.

The game also said goodbye to an outstanding defensive guard in Slater Martin, who won five NBA titles, and some tough forwards in Bob Boozer, Orlando Woolridge and Dan Roundfield. Art Heyman, one of Duke's great players - no small thing at such a school - died at 71.

The coaching ranks also were diminished: Gene Bartow, 81, who succeeded John Wooden at UCLA; and Majerus, 64, who kept turning out winners in 25 years of working the sidelines with plenty of laughs along the way.

The NFL is now without two compelling figures straight out of central casting.

Ben Davidson, 72, was a menacing 6-foot-8 defensive end with a handlebar mustache, epitomizing everything nasty of those Oakland Raiders of yore. He later became a TV pitchman and actor.

Alex Karras, 77, was a defensive lineman for the Detroit Lions, and one mean hombre. He ceded no ground to Commissioner Pete Rozelle when suspended for gambling in 1963. Much later, afflicted with dementia, he joined thousands in a lawsuit against the NFL over head injuries. Karras showed a comic touch in the "Monday Night Football" booth and in movies, notably "Blazing Saddles." Not everyone levels a horse with a roundhouse punch.

Art Modell, one of the NFL's most important owners, died at 87. He moved his Browns from Cleveland to Baltimore, a decision that shadowed him the rest of his life. Darrell Royal, 88, was all folksy in giving football the wishbone offense while winning two national championships at Texas.

Two tough running backs passed on: Alex Webster, who starred for the New York Giants in the `50s and `60s and later coached them, was 80; Steve Van Buren, the heart of the Philadelphia Eagles who played on title teams in 1948 and `49, was 91. R.C. Owens, the San Francisco 49ers receiver who soared over defenders and gave sports the phrase alley-oop, was 77. Steve Sabol, 69, was half of the father-son team at NFL Films, which recast Sunday games as battleground collisions of mythic forces.

The clatter of pins silenced for a moment with Don Carter's death at 85. With his hunched shoulders and cocked elbow, Carter was known as "Mr. Bowling," and with the game spreading across the country in the 1960s he was the sport's first superstar.

In the 1970s, Giorgio Chinaglia, 65, commanded the stage of the North American Soccer League. The great goal scorer played on the Cosmos with Pele and Franz Beckenbauer, and comported himself as if starring in a grand Italian opera. When asked after games why he did this or that, he would stand by his locker in his elegant bathrobe and majestically proclaim: "I am Chinaglia."

Sarah Burke was a pioneering freestyle skier from Canada and a four-time Winter X Games champion. She crashed during a superpipe training run in Utah and died nine days later at 29.

Greco-Roman wrestler Jeff Blatnick, 55, was diagnosed with lymphoma in 1982. Two years later, he had a gold medal around his neck at the Los Angeles Olympics. He went on to become a motivational speaker and Olympic commentator.

Beano Cook, 81, knew all about commentary. He was the studio voice of ESPN college football, his knowledge of the sport vast, as was his repertoire of jokes and stories. He breathed the game in all its school colors.

And all of sports - from anyone who ever broke a sweat in a health club or basement workout room - owes a large debt to William Staub. He redesigned the treadmill, taking the equipment out of doctors' offices and putting them in homes and gyms. He was 96 and was on a treadmill a couple of months before he died.

Said son Gerald Staub: "I don't think he thought it was going to be quite as big as it was."

AP sports writers Genaro C. Armas in State College, Pa., and Ronald Blum in New York and AP writer Katie Zezima in Newark, N.J., contributed to this report.

© Copyright 2012 The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.