Gangs Of Detroit: Examining Youth Violence

By James A. Buccellato, Ph.D.

Special to CBS Detroit

As anyone who's tuned in the news lately knows, crime reduction is a primary goal of Detroit mayoral candidates Mike Duggan and Benny Napoleon. Both have crime fighting credentials: Duggan was a Wayne County Prosecutor while Benny Napoleon served as Wayne County Sheriff.

Each candidate recognizes the epidemic of violent crime in the Motor City. Registering almost 400 homicides in 2012, Detroit ranks as one of America's most violent cities. These statistics are particularly alarming considering that national crime rates are on the decline. According to FBI measurements, 2012 violent crime rates were 12.9 percent lower than 2008 and 12.2 percent lower than 2003 levels. Yet as national crime rates trend down, Detroit's violent crime levels are on the rise.

Tragically, Detroit's youth often find themselves at the center of street violence. In 2010, for example, the city registered 106 youth homicides while apprehending 12,000 young people for criminal activities.

When law enforcement examines this problem they often find gangs at the nexus of youth violence. The National Gang Threat Assessment (NGTA) report, for example, indicates that almost 50 percent of violent crimes are gang related. The report also notes there are 1.4 million active "street, outlaw motorcycle gang, and prison gang members" in the United States. Overall, there are 33,000 gangs within the United States, a 40% increase from 2009.

But what is the situation in Detroit? Is there a strong correlation between street gangs and youth violence in the Motor City?

Providing an answer is difficult, as experts rarely agree on what we mean by the term "gang." Researching Chicago gangs in the 1920s, sociologist Frederic Thrasher observed that "no two gangs are alike." Today, most social scientists agree with Thrasher and categorize gangs into different typologies, assigning gangs varying degrees of criminality.

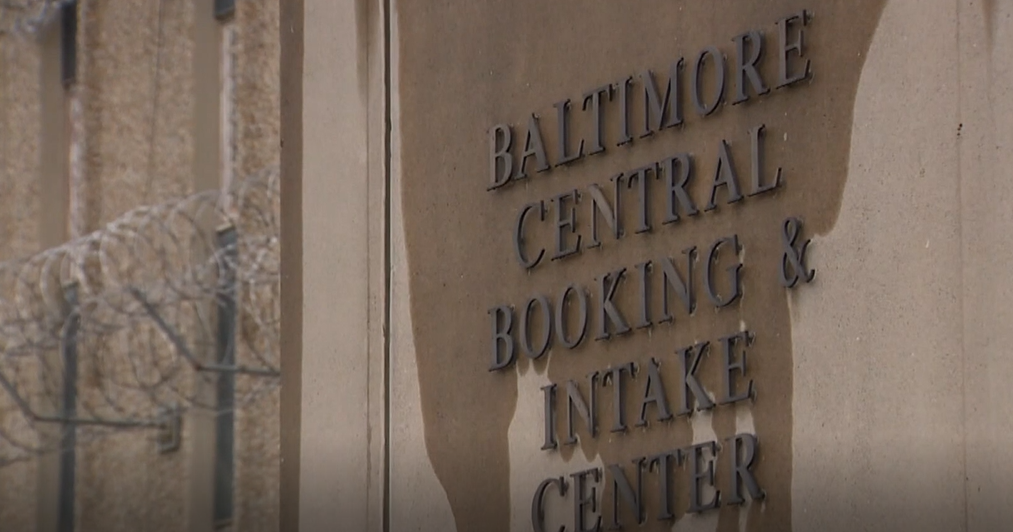

From law enforcement's perspective, however, the gang is a primarily an organized criminal entity. The NGTA report breaks the gang into four categories: street, prison, outlaw motorcycle, and neighborhood. Researchers refer to the top layer of criminal gangs as "corporate gangs." Such gangs maintain vertical structures and operationally resemble ethnic criminal organizations like the Italian mafia.

Over the years, Detroit produced a number of infamous corporate gangs with colorful names like the Purple Gang and YBI (Young Boys Incorporated). While the Purples dominated the bootleg trade during Prohibition, YBI sold copious amounts of cocaine during the 1980s.

In recent years a handful of Detroit based corporate gangs emerged as major players in the narcotics trade and federal law enforcement acted accordingly. In 2003, the Drug Enforcement Administration busted up the Puritan Avenue drug ring for running multistate cocaine operations. Two years later, federal agents took down the Black Mafia Family (BMF) for running a multimillion dollar cocaine empire.

And in June, 2013 the U.S. Attorney's Office sentenced the leader of the Hustle Boys to thirty years in prison for witness tampering and trafficking prescription pain pills in multiple states.

Though corporate gangs grab newspaper headlines, researchers find that such gangs are uncommon in the Motor City. Experts agree that Detroit's gangs are primarily neighborhood based, rather than franchises in some national crime network.

Unlike the hierarchical gangs of Chicago, or the institutionalized gangs of Los Angeles, Detroit gangs form around smaller neighborhood cliques. And unlike Chicago and Los Angeles, the gang situation is fluid in the Motor City.

"A new gang starts every week, while another dissolves" comments Lyle Dungy of the Detroit Crime Commission. Dungy is a Marine and retired Detroit Police officer and served on the Department's Organized Crime Task Force. He adds that while there are a few national brand name gangs like the Latin Counts in Southwest Detroit, most local gangs revolve around a school district or some other neighborhood affiliation. That doesn't mean they are any less violent, but are organic formations rather than the product of some centralized national conspiracy.

In terms of involvement in the drug trade, Dungy notes that "Dirty Sprite" is the chic drug with today's neighborhood gangs. The drink is prescription codeine syrup that party goers mix with soft drinks like Sprite. "On the streets, the syrup can go for $800 a bottle or $40 a line" comments Dungy.

While a local gang member may find the prescription drug business lucrative, it is very different from the vertically integrated distribution systems run by nationally syndicated gangs. According to local film-maker Al Profit, the notion of the corporate gang is obsolete in the Motor City. Profit has documented the issue of crime in Detroit through such films as Rollin and Motown Mafia. He maintains that today, the combination of RICO (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations) laws and "draconian mandatory sentencing makes it impossible to build an organization of the same magnitude as YBI."

Ironically, neighborhoods are in some ways more dangerous when the gang situation is fluid and decentralized. According to Profit, during the 1980s and 1990s "working people were involved in these larger gang operations and as result there was a code on the streets." For example, organizations like YBI would "keep stick-up guys out of the neighborhood, keep breaking and entering to a minimum, and make sure the grass was cut." Researchers still see some of this code in Southwest Detroit with brand name gangs like the Latin Counts. "These gangs are smarter, they keep violence to a minimum so as to avoid police surveillance," adds Dungy.

Spatially the game has changed for Detroit gangs as well. While the neighborhood is the nexus of gang activity, cyberspace is increasingly important terrain for violent youth. "They tweet, update Facebook, and circulate videos on Youtube," comments Dungy. In many cases, gang members use social media to discuss past crimes and openly display contraband.

Although Detroit gangs tend to form organically, researchers note that because of the internet, a few local gangs are adopting national brand names. Such gangs are not franchises though. Instead, young individuals see the ubiquity of gang visuals streaming across social media and adopt national brands accordingly. "We see local gangs affiliated with Money Over Everything," a gang traditionally found in the American South comments Dungy.

Also, some neighborhood gangs on Detroit's East side, a hot zone for youth violence, claim affiliation with the Bloods.

In terms of territory, multimedia technology is also changing the drug game. Profit explains that "back in the day a street corner may generate $10,000 a day in drug sales. But today with cell phones and laptops drug gangs can arrange dope drops and buys anywhere anytime."

For community activist Yusef Shakur, however, the socioeconomic environment in Detroit is the key to understanding today's youth violence. Shakur is a former member of the Zone 8 gang. Today he is a political writer and is involved in community empowerment projects like the Urban Network. In terms of gang activity, "there is a direct relationship to lack of opportunities" explains Shakur. He adds that young people join gangs "out of survival."

According to the Social Science Research Council, Detroit "has the highest youth unemployment rate (30 percent) and adult unemployment rate (17 percent) of any of the twenty-five largest metro areas." Furthermore, "The data show that education is far less an obstacle in Detroit than diminished opportunities to enter the workforce." Significantly, the Council finds that the "disconnection" between youth and employment is concentrated in the African American community. The report notes that "Detroit's African American youth have disconnection rates of 25.3 percent, as compared with 13.5 percent of whites and 19.2 percent of Latinos."

According to Skakur, the problem of youth violence is not just an economic issue. "We shouldn't talk about at-risk youth, we should talk about at-risk communities." He argues there is a correlation between underdeveloped economic conditions and declining social capital. Today's youth (inner-city and otherwise) no longer find traditional forms of community authority, such as the church, labor union, and local school efficacious. As a result, they seek meaning and self-identity in the gang. "T-Stones, Boys' Town, 12th Street. . . these are today's agents of socialization" laments Skakur.

This search for identity explains the fetishization of cyberspace by today's youth. There is real social currency to "being seen and heard" through social media. Ultimately there is no point being in a neighborhood gang if no one knows.

The forecast for youth violence is bleak according to Shakur. With failing social institutions and few economic opportunities, some Detroit neighborhoods resemble "Third World conditions." Skakur refers to such neighborhoods as "Zombieland." And politically there is no urban agenda at the national level.

Locally, however, the City of Detroit has a "Youth Violence Prevention Strategy." Although the policy does not address poverty, it does include a "comprehensive anti-gang initiative." Part of the City's larger initiative includes a $100 million Skillman Good Neighborhoods grant. The grant emphasizes education and community betterment programs.

Meanwhile, in August, 2013 the Detroit Crime Commission persuaded Detroit PD to reinstitute "the gang squad." In terms of joint federal and local policy, the Eastern District Court recently unveiled "Operation Cease Fire." The initiative is a $1.5 million grant that includes a combination of law enforcement and social assistance.

As for the mayoral candidates, each highlights his crime fighting qualifications.

Napoleon reminds voters that he led the Detroit PD Gang Unit that battled notorious drug organizations like the Chambers Brothers. Duggan, meanwhile, reminds voters that as Wayne County Prosecutor he shut down "over 900 drug houses" in Detroit.

Overall, Skakur argues that going after gangs is "too easy." Until policy makers and community leaders address economic development and declining social capital, the gangs of Detroit will persevere.