Toxic plastic pollution is everywhere, even clogged arteries. We asked a Colorado doctor how to stay healthy.

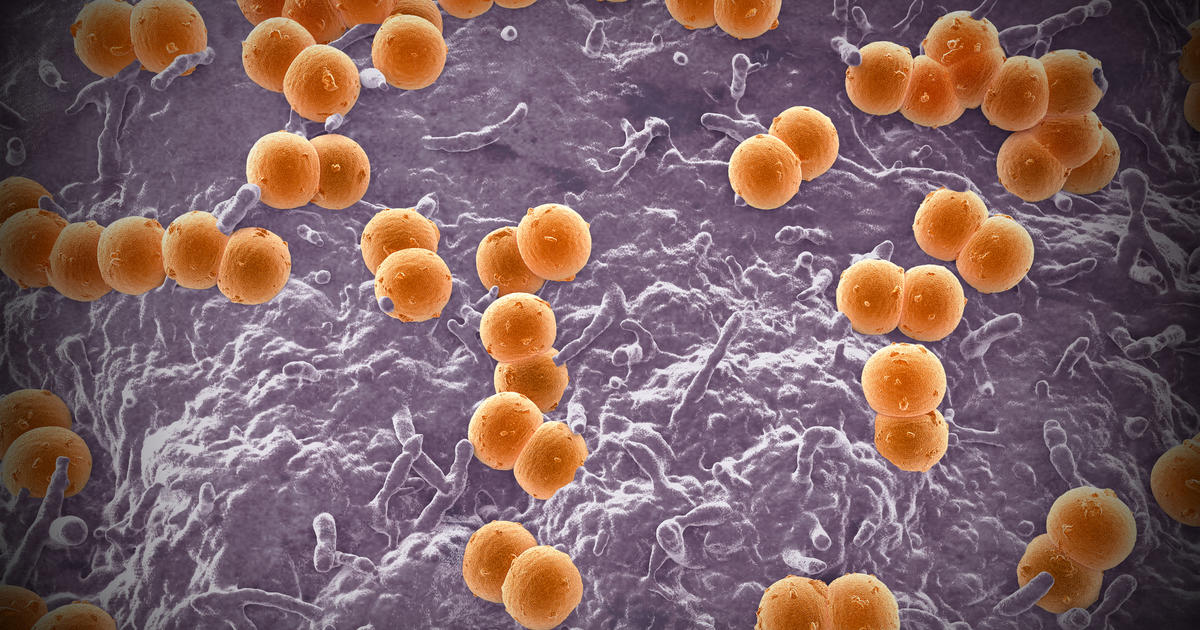

Micro- and nano-scopic sized pieces of plastic people use everyday can eventually find its way into the most unlikely of places, even in the plaque of clogged arteries of cardiac patients, a recent study found.

In the study, researchers in Italy reported finding "visible, jagged-edged foreign particles among plaque macrophages and scattered in the external debris."

The researchers said the chemicals in those foreign particles were polyvinyl chloride, or PVC, and polyethylene, two of the most common materials used in everyday, household plastic items, like water bottles and PVC pipe.

A separate recent study found there are 100 to 1,000 times as many pieces of plastic in a bottle of water as previously thought, and in another study from Yale, Americans who consume water from plastic bottles consume an estimated 90,000 more microplastic particles annually than people who only drink tap water.

This week, Colorado has been covered in a gray haze of wildfire smoke and air pollution. Other studies have found microplastic particles can not only be ingested via the beverages we drink or the food we eat, but it can also be inhaled through the contaminated air we breathe.

The Yale study estimates Americans ingest and inhale on average up to 121,000 microplastic particles a year.

Last year, students and environmentalists in the Denver metro area found microplastics in 16 major Colorado waterways -- every single waterway they tested across the state.

Inside those chemicals, a controversial compound of durable chemicals can often be found: PFAS, or per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, commonly called "forever chemicals" because of their durability.

What makes plastics so great for household products is that they don't readily break down. But that's a problem once those chemicals are in our bodies — they just break up into smaller and smaller pieces, and continue to accumulate.

"PFAS particles are unique, because our body doesn't degrade them very well... ordinarily we have chemicals that break almost everything down that we're exposed to, but these molecules are resistant to those normal processes, so we tend to accumulate them," explained Dr. Anthony Gerber, a pulmonologist at National Jewish Health. "I think the big question is, in addition to accumulating them, are there structures within those forces that are also changing what cells do? So are they having a direct effect on cellular function, in addition to just sort of accumulating and sticking around?"

While Gerber did not work on the Italy study finding microplastics in artery plaques, he has been examining the ways in which pollutants interact in the body.

"There's this widespread sort of literature on what we call endocrine disruptors... different chemicals that have enough of a chemical match for our normal hormones that they can kind of operate and wind up taking over some of the same body's signaling and machinery that responds to hormones," Gerber explained. "We know that PFAS aren't really strong endocrine disruptors, but they've also been shown to have weak activity, for example, in progesterone or estrogens, and so one of the questions is 'does that weak activity translate into something that might cause disease?'"

But he added, "the other issue is, because they stick around for a long time, that accrual over time of having cells, which might have this higher exposure to hormonal signaling, could have an effect... and then the fact that they're so persistent, could give you a mechanism where even a little bit of activity could wind up changing cellular behavior and promoting disease or other issues."

In the study from Italy, researchers reported that people with microplastics in the plaque of their arteries were more likely to suffer more serious outcomes, including heart attack, stroke, or death.

In a different study, scientists found higher amounts of microscopic plastic particles in the feces of people with inflammatory bowel disease.

While some recent studies are finding some associations between PFAS and microplastic exposure with serious medical conditions, Dr. Gerber says many more studies are needed.

Meanwhile, the EPA has deemed some PFAS compounds that have been more readily studied as toxic to humans.

For the first time ever, the EPA passed laws this year limiting certain PFAS in drinking water, and Colorado passed laws that will eventually ban the sales of certain products with PFAS, like dental floss and feminine hygiene products.

But still these chemicals are basically unavoidable in the world around us. They're in everything from flooring to clothing to food wrappers and water bottles.

With the latest study out of Italy, we're learning they may be building up in our bodies in an even more intrusive way than ever imagined.

Gerber says the microplastics study in Italy was a novel approach, and will likely inspire more like it in Colorado.

"It definitely opens up a potential way to start to do those comparison studies, which are so important for establishing a link between the chemicals, the plastics, and the PFAS being in the plaque, to actually being causal or changing the way the disease is presenting," Gerber explained.

So what can we do to protect our health, despite these tiny particles lurking all around us?

Experts say limiting your exposure to plastics and PFAS are a good step. For example, use glassware instead of plastic containers, call your water utility to ask about PFAS testing results, and filter your water if necessary.

But most importantly, Dr. Gerber reminds us not to forget the basics of living a healthy life, like eating a healthy diet, avoiding processed foods, and exercising regularly, which he says helps protect the body and strengthens cellular function.

"If microplastics might be promoting coronary disease, you might not be able to avoid ingesting the microplastics, because they're everywhere, but you can sure do the other things. You can keep your blood pressure low. You can exercise. You can get your cholesterol measured," Gerber said. "So my advice would be to do all the things that we already know are beneficial to mitigate whatever unknown risk there might be from some of these chemicals."

The American Chemistry Council, which represents more than 190 companies engaged in the business of chemistry, many of which manufacture and utilize PFAS and other plastic chemicals, provided the following written statement in full to CBS News Colorado for this report:

"The authors of the most recent study on microplastics and cardiovascular health, Marfella et al. (2024), point out that the results do not prove a link between microplastics and cardiovascular disease. They also cite several factors that – had they been accounted for - could have affected the study results. These include a patient's socioeconomic status, lifestyle patterns such as food intake or alcohol use, and sample contamination.

"The study of microplastics is relatively new and evolving. The global plastics industry is helping to advance scientific understanding of microplastics and reduce plastic pollution that can become a source of them in the environment – both key recommendations in the World Health Organization's (WHO) 2022 report. Our industry has committed $15 million to fund independent research, with more than $7.4 million disbursed since 2021 to academic institutions around the globe.

"Additionally, through the International Council of Chemical Associations' (ICCA) Microplastics Advanced Research and Innovation Initiative (MARII), we've created a global platform to help scientists, academia, and research institutions share information and collaborate on microplastics research. ACC supported the Save Our Seas 2.0 Act, bipartisan legislation which provided funding for more research on microplastics.

"Regarding chemistry production and use, ACC's members are committed to producing chemistries that offer important safety, product performance and durability benefits and that can be used safely. Our members undertake extensive scientific analyses to evaluate potential risk of their chemicals, from development through use and safe disposal. We work with regulators, retailers and manufacturers to provide them with information about our chemicals.

"Meanwhile, we continue to work with EPA, FDA and other federal agencies to strengthen our regulatory system and help ensure that policies are made using the best-available science and the weight of the evidence to make decisions. In fact, chemicals in commerce are subject to government oversight, primarily by six federal agencies (CPSC, DHS, DOT, EPA, FDA, and OSHA), under more than a dozen federal laws and regulations. Today, chemistry products introduced or imported into the U.S. undergo rigorous review and approval processes by federal agencies, such as EPA and FDA."