Colorado Bill Would Limit Ketamine Use By Paramedics, Police

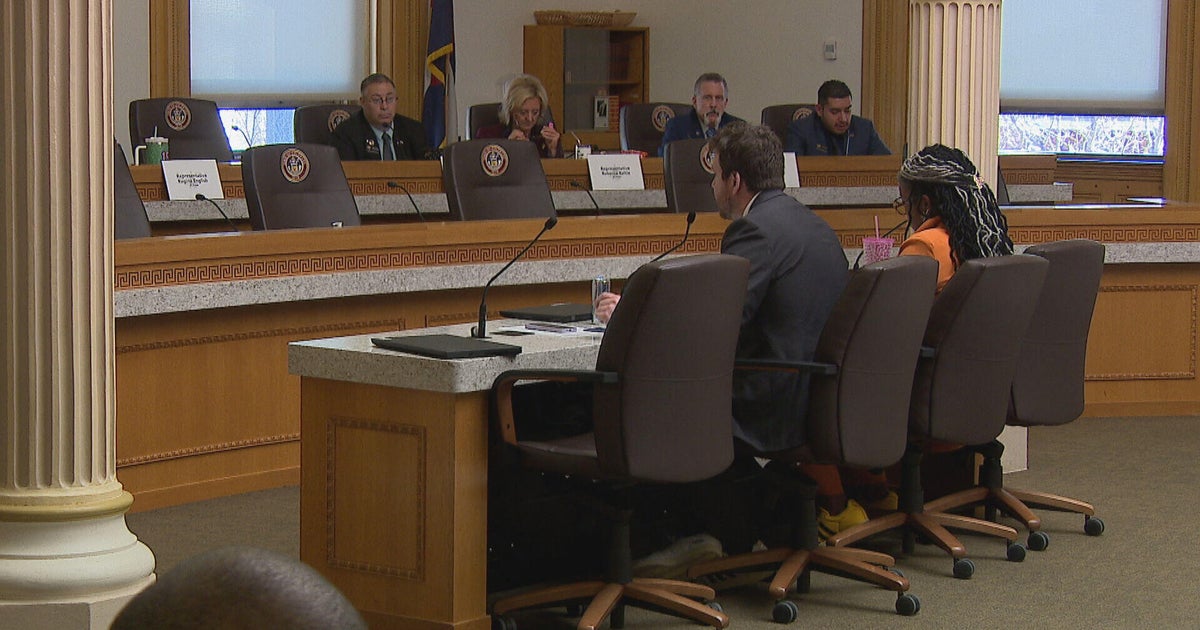

DENVER (AP) — A Colorado bill aims to limit the use of ketamine in law enforcement encounters, almost two years after the death of Elijah McClain, a Black man who was injected with the drug while under arrest in suburban Denver in 2019. The bill, which was passed on Monday by the state Senate Judiciary committee, would prohibit paramedics' use of ketamine to "subdue, sedate, or chemically incapacitate" people in police custody if the situation is "absent a justifiable medical emergency."

McClain, 23, was stopped by Aurora police officers responding to a 911 call about a suspicious person wearing a ski mask and waving his arms. Police put him in a chokehold and multiple officers pressed their body weight into him.

Paramedics were called and injected McClain with 500 milligrams of ketamine after they incorrectly estimated his weight, giving him more than 1.5 times the dose he should have received, according to medical standards.

McClain suffered cardiac arrest, was declared brain dead and taken off life support less than a week later.

The bill also prohibits a peace officer from directing, or unduly influencing an emergency medical service provider to administer the drug. Peace officers and paramedics must report any officer's violation within 10 days. Failure to do so would be considered a misdemeanor.

Paramedics who administer ketamine would have to weigh the individual for accurate dosage or have two trained EMS providers agree on an estimated weight, if the bill passes. First-responders would also have to use equipment to manage respiratory depression, monitor patient vitals and be able to provide urgent transportation and record any complications.

Under the bill, paramedics must also have training for ketamine administration and advanced airway support.

Anita Springsteen, an attorney and city council member for Lakewood, a suburb of Denver, said she witnessed and recorded a video of when paramedics injected Jeremiah Axtell with ketamine despite him being restrained to a gurney and having told police multiple times that he would cooperate.

"People in the United States should not be forcibly injected this way or given death sentences this way without due process," she said.

Axtell, who also testified before the committee, said drugs shouldn't be forced upon anyone in any circumstance.

"When they got me with ketamine it messed me up. I can't do anything right anymore," Axtell said. "And I'm not the only one. There's people that wanted to speak here, that are scared."

Witnesses representing police, firefighters and paramedics who testified in front of the committee, said the use of ketamine is important for first-responder's safety in volatile situations. They also said the bill could hinder communication between first responders for fear of being criminalized.

Gary Bryskiewicz, chief paramedic for Denver Health Paramedics said without ketamine, first-responders only have access to other "slow-acting options" which could put them in danger when dealing with "uncooperative and violent patients."

"Ketamine could take affect in almost half time as other pharmaceutical options and has predictable sedative outcomes. Ketamine causes less respiratory depression than benzodiazepines which makes it a safer option in the agitated patient," Bryskiewicz said.

Law enforcement groups made up of Colorado police and sheriffs said in a statement that they're worried the measure would make peace officers criminally liable for the actions of paramedics or for expressing concern about patient well-being and the need for emergency medical care.

The penalty, they add, could be 18 months in jail, a $5,000 fine and a loss of their certifications and livelihoods.

In Colorado, the emergency medical practice advisory council oversees and grants waivers to agencies to be able to use ketamine. The new bill would direct Gov. Jared Polis to appoint an anesthesiologist and a clinical psychiatrist to the council.

The advisory group would also have to submit a report to Legislature any time they advise or recommend any new chemical restraints.

The state health department would be required to submit annual reports on the statewide use of ketamine by paramedics and any complications to the Legislature starting in 2022 and be publicly available on the department's website.

The bill will go to the Senate Appropriations committee next.

By PATTY NIEBERG Associated Press/Report for America

Nieberg is a corps member for the Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.

(© Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.)