Colorado racial terror lynching victim Preston Porter Jr. remembered after 122 years

A historical marker erected in downtown Denver aims to educate Coloradans about an incident of racial terror that happened on this day 122 years ago.

On November 16, 1900 a fifteen year old boy named Preston Porter Jr. was lynched by a white mob outside of Limon.

Although the incident drew national outrage at the time, few in our state were aware of the lynching until recently.

"I didn't realize that there was racial terror lynching in Colorado," said Pennie Goodman, of the Colorado Lynching Memorial Project.

Judy Ollman, a liaison with the Equal Justice Initiative said, "This happened in Colorado? I had that same concept."

In 2010, the Equal Justice Initiative began investigating racial terror lynchings across the United States, mainly in the American South. Many of these had never been documented.

Professor Stephen Leonard is a historian at Metropolitan State University of Denver who has researched and published about lynching in Colorado. He said, "Oftentimes we like to live in our imaginations because they can be made more pleasant than the reality. There were more than 160 people lynched in Colorado between 1859 and 1919. Some of them were Black and many of them were of Mexican ancestry."

Members of the Colorado Lynching Memorial Project traveled to Limon in 2018 to hold a soil collection ceremony.

It was near where 15-year-old Preston Porter Jr. was burned to death in front of hundreds of people on Nov. 16, 1900.

Ollman said, "This was just horrendous. It was appalling."

"He was 15 years old and I can't help but put myself in his position," said Goodman. "This boy being dragged and tied up, can you imagine the terror and the fear?"

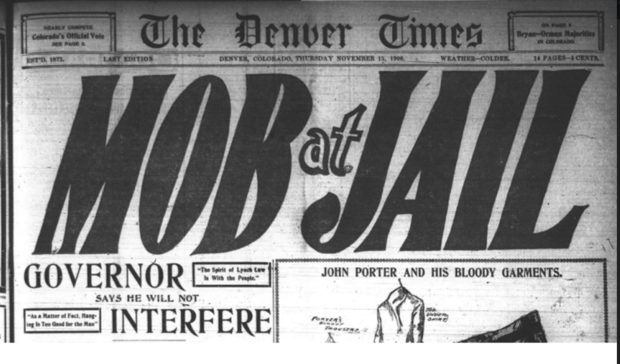

Preston Jr. had come to Colorado from Kansas with his father and brother to work in railroad construction. When a young white girl names Louise Frost was found murdered in Limon, Preston's family was stopped in Denver for questioning, but they denied involvement.

Authorities zeroed in on young Preston and placed him in a sweatbox at Denver City Hall. He was told his family would be lynched if he didn't confess.

MSU historian Stephen Leonard said, "That's why we have prohibitions against torture. And he was tortured. A lot of people will confess to things that they didn't do if they're threatened enough and tortured enough."

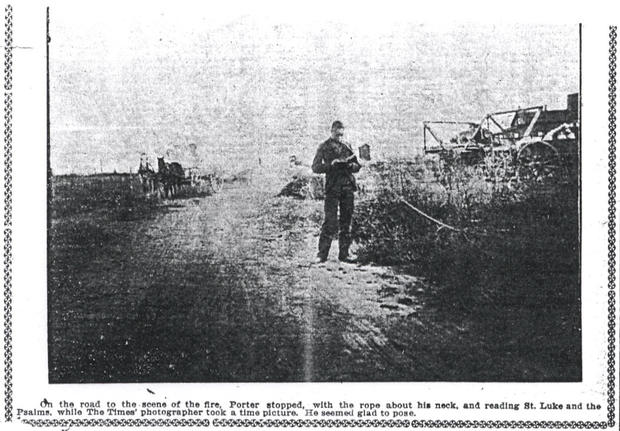

Preston was placed on a train to Limon, a white mob seized him and made him wait tied to the tracks while a crowd gathered.

Ollman said, "They were asking for souvenirs and so he tore pages out of the Bible to give to people for souvenirs."

News accounts at the time reported that as he was set on fire, Preston asked God to forgive the people doing this and to have mercy on the family of the murdered girl.

"It's very interesting to read the articles after this happened," said Ollman. "And how shocked and horrified so many people were."

A group of ministers in Chicago wrote to President William McKinley about Porter Jr., asking him to introduce legislation to prohibit lynching and to hold mobs criminally liable.

After nearly 122 years, the Emmit Till Anti-Lynching Act was signed into law by President Biden this past March.

The Colorado Lynching Memorial Project's Jovan Mays said, "We're not trying to lock people into the past. We're trying to have people take all these lessons from the past and carry them forward so they're not made again."

The soil collected in Colorado will eventually go to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Informally known as the National Lynching Memorial, it commemorates the estimated 6,500 Black victims of lynching in the United States.

Markers like the one in downtown Denver (at 13th and Larimer, north side of Speer Boulevard) are meant to prompt communities to discuss ways to build a future rooted in justice.

On Sunday, November 20th, the Colorado Lynching Memorial Project will hold a remembrance and discussion at Holy Redeemer Church, 2552 North Williams Street in Denver, from 1:30pm to 3:30pm.