Calculating avalanche risk in changing Colorado: A new and evolving science

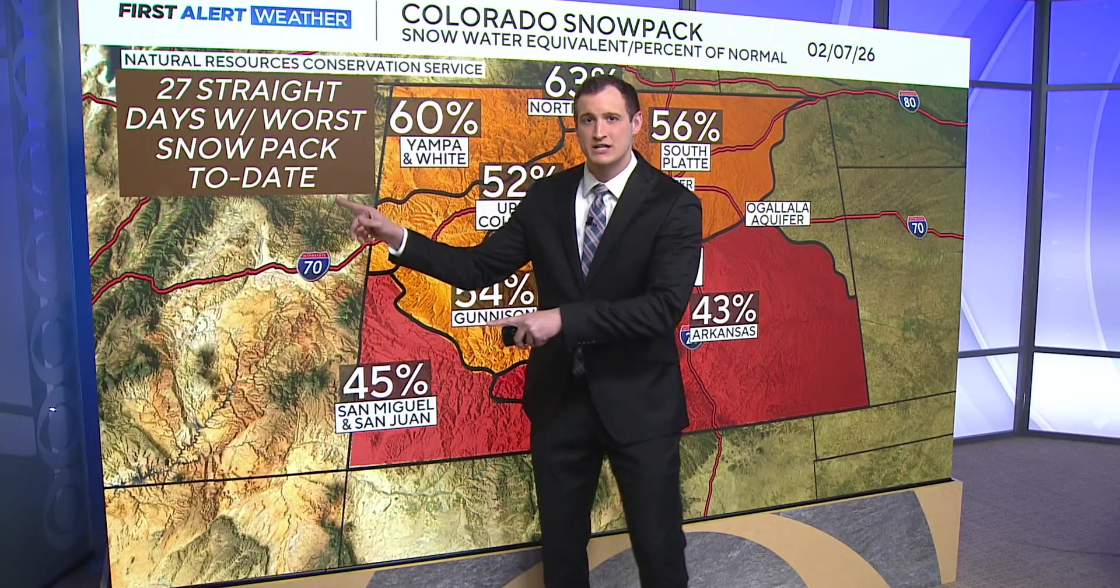

Colorado is entering yet another season of avalanches as another storm is dumping snow in the mountains and along the Front Range.

Avalanches kill more people on an average annual basis in the Centennial State than any other natural disaster. Last season, seven people died in Colorado and in the 2020-2021 season 12 were killed.

"Avalanche science really is a fairly young science, you know it has its roots in the 1920s," said Ethan Greene, director of the Colorado Avalanche Information Center.

The center and its experts are looking at changing avalanche risks as weather and climate are being altered.

"Typically in midwinter Colorado and in the heart of the winter -- you know December, January, February -- when I started my career we would not see rain on snow events. And now we do."

Avalanche forecasters are opening to new possibilities as conditions are altered.

"Certainly, from our perspective, things are changing and we need to run a program that accounts for some of those changes," Greene said.

While weather records do not represent a great time span, there are decades of information that experts look at when they see slides increase.

"'Is this caused by you know X, Y, or Z?' that's pretty difficult," said Greene, "but we can certainly look through the records, and we can see what has been recorded in the past and in Colorado we have pretty good records going back into the 80s and 70s and even back into the 50s in a couple of places."

What that tells them is that during most of that time there was a typical range of avalanches. But in recent years that has broadened.

"So you could really talk about things that that person had seen before, or maybe, their predecessor had seen and those sort of bookended. The events that we thought could happen, and I think we're a lot more open," said Greene.

One of the most stunning years was 2019. There was a plague of avalanches in March, including one that rolled over Highway 91 between Copper Mountain and Leadville.

"During that March of 2019 cycle we saw avalanches that we feel pretty comfortable calling over 200-year events," said Greene.

Forecasters are seeing new possibilities that they realize are potentially more likely.

"Some of the events that we might see could be outside of our own personal experience," Greene said. "We've also just in some of our forecast tools to be able to look at, not necessarily outlier events, but events that are more on the fringes of what we would see, day to day throughout the winter."