30 Years Ago On CBS 2: Walter Jacobson Experiences Homelessness Firsthand For 48 Hours In 'Mean Street Diary'

Written story compiled by Adam Harrington, CBS 2 Web Producer

CHICAGO (CBS) -- Homelessness is an ongoing crisis in Chicago and throughout the country – with added pressures today from the coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing unemployment crisis.

This February 2021, an Arctic blast has settled on the city and made the crisis even more urgent – especially since shelters have lowered capacity during the pandemic. Some of those left outside in Chicago have suffered from hypothermia in the cold, and advocates and organizations have been stepping up to help.

In "Mean Street Diary" – a six-part series of reports that began 30 years ago Wednesday on CBS 2 – Walter Jacobson approached the homelessness crisis in a manner that went beyond only reporting. He became homeless himself for 48 hours in the dead of winter as temperatures bottomed out at 11 degrees below zero – looking for food, a place to sleep, and a way to survive.

We first posted "Mean Street Diary" to the old cbs2chicago.com website back in 2007. This is an adapted and updated version of the written story we prepared to go with the archive video reports at that time.

Part I (aired Sunday, Feb. 17, 1991; video above):

Jacobson began his project on Lower Wacker Drive, where he had been many times before interviewing the homeless under the warm air vents in the garages above, and in the cardboard boxes.

But this time, Jacobson was looking for warm air and a cardboard box for himself, and some understanding, if possible, of what it is like to be homeless. He reported it turned out that many of the homeless are driven underground – literally – by perceptions of danger in shelters and soup kitchens and constant rejection in places where the rest of the world is free to go.

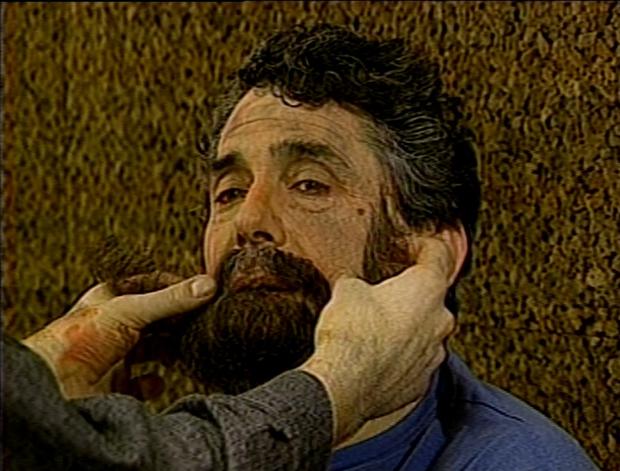

Jacobson donned a ratty coat and hood, and wore a disguise in which a makeup artist turned his teeth yellow, fashioned bags under his eyes and gave him a scruffy artificial beard. And then Jacobson set out on the streets of Chicago with just $3 in his pocket, accompanied by a CBS 2 news crew with a hidden camera.

"I think the hardest part is going to be finding a way to relate honestly to people who are homeless," Jacobson said before he started the project.

But when Jacobson began his project on an overcast afternoon with the mercury dropping below zero, his thoughts quickly turned to more immediate needs.

By just the sixth hour of Jacobson's project, the temperature had dropped to 11 below zero. In search of some heat and a meal, he headed for the Olive Branch, a shelter on Madison Street near Morgan Street.

But he found looking for food is never simple for the homeless, and it can even be dangerous. At the Olive Branch, security guard checked everyone for weapons, because on the street, you just never know.

"I need your gun, your pistol, knives, ice picks, whatever," the guard said.

Jacobson was surprised at the concern in the Olive Branch about weapons. His next stop was at Nick's Fishmarket, a high-end restaurant in what is now the Chase Bank Plaza downtown, where he asked a man whether he might be able to get a cup of coffee there.

"They don't let you in there like that," the man replied. "They only let you in there if you have a suit."

"What the hell is the difference?" Jacobson said.

"I don't know, but to them, there is one though," the man said.

But it was not just fancy restaurants where the homeless were made to feel unwanted. When Jacobson stood in front of some rotisserie chickens turning over an open fire at a restaurant at Clark Street and Fullerton Parkway in Lincoln Park, he was directed to go away.

Jacobson also went to City Hall, which he reasoned might be a good place to get in out of the cold and possibly even find help. When a police officer approached, the disguised Jacobson claimed he was planning to meet a friend who was walking through.

A police officer told him to move along, directing him to the Cook County side of the building.

"But I told him I'd meet him at City Hall," Jacobson said.

"Go on down to that end," the officer said. "I'm not going to argue with you."

Jacobson was discouraged by the experiences.

"With an attitude like that, it's no wonder the homeless go underground," he said in a voiceover after the exchange with the police officer at City Hall was shown.

Jacobson went underground for his project too. On Lower South Water Street, Jacobson at one point asked a homeless man why he would not go to the shelter, which made the man upset.

The man could not explain why he would not go to a shelter, but in 48 hours, Jacobson came to understand his own feelings about it. This quote became well-known, and while it aired in the first installment of the series, he actually said these words toward the end of his 48 hours when he was reaching a breaking point:

"You may think this is an act for the television camera, but I'm telling you I am really miserable – really, really miserable. I don't even know – where do you go? Where do you go next? What do these guys do?"

Part II (aired Monday, Feb. 18, 1991):

As Jacobson wandered along Lower Wacker Drive and elsewhere in the city, he met several homeless people who appeared hardened to their situation.

He found one man who for that night appeared content sleeping in a cardboard box. The man said: "I don't put all that time worrying. My problems are in the hands of Jesus and God."

Jacobson began looking for somewhere to spend the night himself. It was 1 a.m., the wind chill was -17, and he was out of money as he walked the street. He passed a diner that had gyros turning on a spit.

"Oh God, there was gyros in there," Jacobson said as he looked in the diner window. "What I'd give to walk in and just ask if I could have a sandwich. I haven't got the nerve to do that."

But finding a place to sleep was even harder, and turned out to be impossible that night.

Jacobson first headed for the shelter that operated at the time at the Clarendon Park Field House in Uptown, looking forward to experiencing the comfort of a warm bed. But there was no such luck.

"We're full," a shelter operator said. "We already had to turn away a dozen guys."

The shelter operator was sympathetic, and told Jacobson to go to a police station where the city's Department of Human Services would pick him up and take him to the nearest shelter. He also said to flag down a police officer.

Jacobson flagged down some officers, and they waved him away. So he went to the old Town Hall District police station at Halsted and Addison streets in East Lakeview, and made his call to the Human Services Department.

They told Jacobson to sit tight. But he was left in the vestibule.

"I sure don't feel wanted in there, I'll tell you that," Jacobson said as he sat on the police station vestibule stairs, "like I'm the plague."

He ended up lying down on the stairs at 3 a.m. But at 4 a.m., he was still awake.

"I can't think of a night I've ever spent in my life that's been more miserable than this," Jacobson said.

The worst, Jacobson said, was the officers inside, who told him to dial the state Department of Human Services on a pay phone. By the time he found one, it was 5 a.m., and too late to sleep.

Part III (aired Tuesday, Feb. 19, 1991; video above with Part II):

As Jacobson also discovered, many public places are not so public for the homeless – even ones where homeless people are seen often.

Nobody gave it a second thought when Jacobson did a live stand-up from Union Station in a suit and tie to introduce his third report, but when he had been incognito as a homeless man two weeks earlier, the train depot was not so friendly.

That is despite the fact that Union Station was a place known for the homeless, along with Lower Wacker Drive, O'Hare International Airport, and back then, West Madison Street where skid row was once located.

But after a few minutes, a security officer ejected Jacobson.

"There's a lot of the homeless people that cause problems, unfortunately, which makes it bad for all of you guys who aren't so bad," the security officer said.

So Jacobson hit the streets to figure out a plan. He discovered that some homeless people who know the streets and know the system are able to beat the public rejection Jacobson was encountering.

One man named Dennis was found panhandling in the Loop. He had made $82 in just under four hours.

Of that time, Dennis said he spent "half the time in church warming up, so say like two and a half hours actually with hands out."

But not all days were that good for Dennis. And Jacobson was seeing what the homeless experience when they are not so lucky.

Briefly thinking he had lost the little money he had left, Jacobson walked through the food court at the Thompson Center, then known as the State of Illinois Center. He found that he did still have his remaining money after all, but was not comfortable sitting at a table with strangers.

"This whole eating trip that I've been thinking about for three hours is becoming so anxiety-ridden, I don't want to eat. I'm losing my appetite," Jacobson said.

But with rejection and alienation also came kindness and the beginnings of camaraderie.

Part IV (aired Wednesday, Feb. 20, 1991):

Jacobson noted that homeless shelters often closed at the early hour of 6 a.m., at which time everyone must leave. So it was back into the streets.

He pointed out that many of the homeless are well-educated and spend the day at the Chicago Cultural Center downtown. When Jacobson stopped there, several people were sitting at tables, keeping up on the Persian Gulf conflict at the time and waiting for their shelters to reopen.

A man named Andre, who was lying down surrounded by a cardboard box on Lower Wacker Drive, read the "INC." celebrity gossip column in the Chicago Tribune and offered to share his resources with Jacobson. Andre offered Jacobson a gift certificate for a restaurant, which Jacobson did not take.

Another man talked with Jacobson about where to get food, but when Jacobson asked him why he did not go to a shelter, the man became furious.

"I don't want to go to no damn shelter!" the man said. "Don't ask me about no damn shelter!"

Jacobson reported that many homeless individuals do not go to shelters because they do not want the regimen or to attend church services that may be required. Often, they prefer only to be alone.

Then, Jacobson noted, there are the homeless who seem always silent. They are willing to share their space, but not their thoughts.

After warming his hands over a fire a man had made in an empty steel drum, Jacobson offered the man a dollar, which the man hesitantly took, barely speaking as he did so.

Jacobson's generosity was returned when a young man handed him some spare change without his even asking at a downtown Chicago Transit Authority subway station.

His spirits were lifted again that night, in the nearly-deserted Wilson Avenue Red Line station in Uptown.

"Just have a seat, get warm, leave whenever you feel like leaving," a CTA security officer said.

If not for such acts of kindness, Jacobson reported, there are many homeless people who would not make it through the winter.

And often, finding a shelter was difficult, even though shelters were set aside especially for the homeless.

Part V (aired Thursday, Feb. 21, 1991; video above with Part IV):

Jacobson noted that then-Mayor Richard M. Daley said at the time that there was enough shelter for all the city's homeless. But Jacobson reported that was not when he found, and he compared the plight of the homeless trying to find shelter to old-time Chicago politics.

"This is the Windy City, remember, where even among the homeless, it is the clout that counts," Jacobson said in his live standup before the night's diary installment.

On his second night on the streets, Jacobson returned to the shelter at Clarendon Park, but not before trying some other options.

Jacobson first went to a church at Wellington Avenue off Broadway, which was full. He was turned away, and told he needed a referral to be there.

At the Lincoln Park Presbyterian Church at Fullerton Parkway and Geneva Terrace, a shelter worker said Jacobson was not a regular and there was not room for non-regulars. But Jacobson got the impression that it was because the worker did not like the way he looked.

Jacobson spent the next four hours and seven or eight miles looking. He was turned away from shelter after shelter, many of which wanted references from other shelters and would not consider taking him in without one. They did not want a risk of trouble.

Ultimately, Jacobson got on a pay phone and was told he needed to go back at the Clarendon Park Field House, operated by the Chicago Park District. It opened at 11 p.m. on a first-come, first-serve basis, and Jacobson was determined to arrive on time. It had been two nights since he'd had any sleep at all.

He met another man waiting to get in who said he had slept under a church the night before.

"It was easy. I got a blanket; a little mat," the man said. "My feet didn't freeze. That's what I was worried about."

Jacobson was told to wait at the door at Clarendon Park, and he intended to be the first in line. But some others waiting for the shelter said people who did not sleep there the night before should move back, and Jacobson did not feel it was safe to refuse.

"If you want to know the truth, I'm good and scared right now. One of these guys decides to pass me in line and what do I do? Tell him no? Then what, wind up dead?" Jacobson said. "I want to get in here to sleep to live. I'd better move back a few places."

This time, Jacobson got in the 45-bed Clarendon Park shelter. Those who did not likely spent the rest of the night walking the streets.

Part VI (aired Friday, Feb. 22, 1991):

At 11 p.m., Jacobson entered the shelter. Everyone who came in was asked for his name and whether he had been at the shelter before.

Upon beginning the Mean Street Diary project, Jacobson knew the statistics on the homeless. The figures as of that time were 10,000 to 40,000 in Chicago on a given night, and the national figure was a third of them suffering from some sort of emotional disorder. And between October 1990 and February 1991, more than 20 homeless people had died from exposure to cold.

But now the faces had been made familiar, and resting at last, Jacobson recalled the people he had seen in the 36 hours up to that point.

"This just isn't how life is supposed to be," Jacobson said as he concluded his project. "There is no way that these people can help themselves. Somebody else, somehow, has to help. It's enough to unhinge me, and when I wake up and go home tomorrow, I'm going to do something. I don't know what, but something."

As to the solutions, Jacobson said, the first thing was to admit there was a problem:

"People in the neighborhoods are so cold and hungry tonight that they're numb. We see them all the time, but we don't really see them."

Epilogue

While the homelessness crisis continues to plague Chicago 30 years after Jacobson's groundbreaking series, many people and organizations have been stepping up.

In November, A Safe Haven is partnering with the Small Business Advocacy Council announced their partnership for a new fundraising campaign to help people struggling with homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

"Fifty-five percent of the small businesses right now may not reopen post-COVID," said Neli Vazquez Roland, co-found of A Safe Haven. "And that means that everyone that worked in these businesses may be facing the possibility of losing their home, losing their livelihoods and losing the ability to provide for themselves and their families."

The fundraising program is called "Rebuilding Lives and Businesses."

If you want to donate, go to ASafeHaven.org or log on to SmallBusinessAdvocacyCouncil.org.

Meanwhile, community advocate Jermaine Jordan this winter has been raising funds to drive around the city scouting people who don't have a place to stay since shelters have lowered capacity due to the pandemic. He said during his trips, he found people with hypothermia – and he even had to take one to the hospital.

Jordan told CBS 2 he is trying to get enough funds to keep the dozens of Chicagoans safe at the hotel and fed for at least a month. If you'd like to help him on his mission, he has a fundraiser you can find here.

And if you see someone sleeping on the streets in these cold temperatures, call 311.