The Great Debate: First televised presidential debate held at CBS Chicago 64 years ago this month

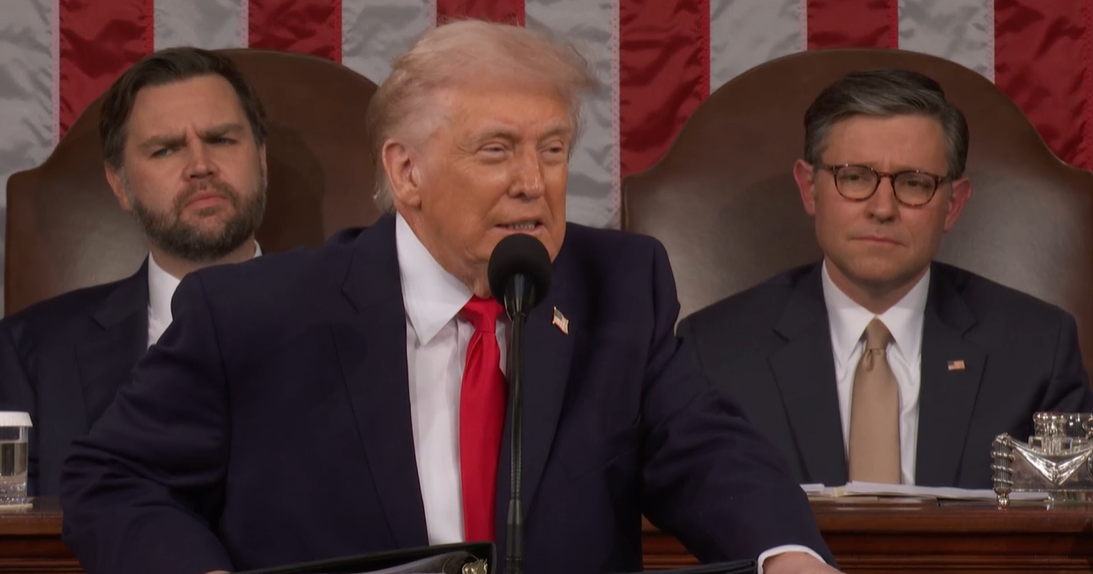

CHICAGO (CBS) -- Former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris will go head to head in a presidential debate in Philadelphia on Tuesday night — continuing a 64-year tradition in television that began at CBS Chicago's old studios.

On Sept. 26, 1960, Vice President Richard M. Nixon and U.S. Sen. John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts met for the first ever televised presidential debate in Studio 1 at the old CBS Chicago broadcast center, at 630 N. McClurg Ct. in the Streeterville section of the Near North Side.

Political campaigns were not new to television in 1960. In 1952, campaign aide Roy O. Disney — older brother of Walt Disney — created the "I Like Ike" campaign for Republican candidate Dwight D. Eisenhower just for television. That same year, the Democratic and Republican national conventions — both at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago — were televised.

Also in 1952, Nixon — amid a scandal over campaign contribution ethics — admitted that he had accepted a gift of a cocker spaniel puppy named Checkers. Four years later, Kennedy made remarks at the 1956 DNC — again held at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago.

In 1960, Nixon and Kennedy each won nominations for the top of the Republican and Democratic tickets for president, respectively. While Kennedy was on an upswing when September came around — telling Protestant ministers in Houston that he could serve both his country and his church as a Roman Catholic — Nixon had suffered an injury to his left knee in a limousine while campaigning in North Carolina the month before and ended up in the hospital with septic arthritis.

Congress suspended the "equal time" rule for broadcasting, thus making it so 14 minor-party candidates running for president in 1960 did not need to be granted equal time. The Democrat Kennedy and the Republican Nixon would debate one-on-one, and millions would be watching.

Some anticipated the debate could make or break a candidate's chances in the election.

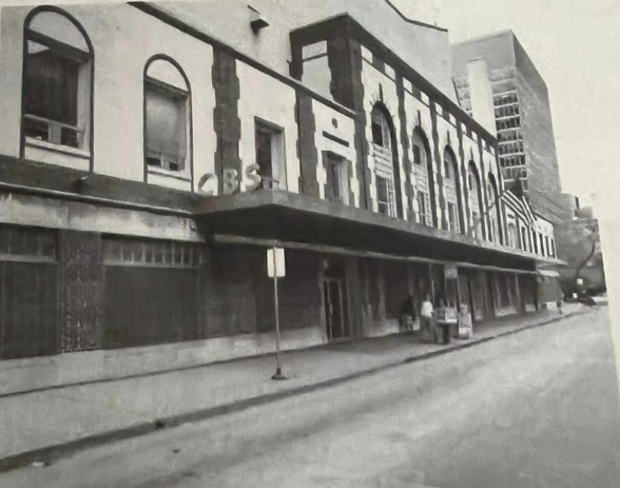

A mass of media at McClurg Court

CBS was selected to handle the first debate at its relatively new Chicago headquarters at 630 N. McClurg Ct. The building had been completed in 1924 as a horse stable for the Chicago Riding Club, and a dozen years later became the Chicago Arena — which offered skating to the public and also hosted figure skating competitions, amateur hockey league games, and the Ice Capades. In addition to its vast ice rink, the Chicago Arena featured a bowling alley, a grill, and a $50,000 Wurlitzer theater pipe organ that was played as accompaniment for the skating.

In 1954, CBS purchased the Chicago Arena building for $1.5 million. The theater organ was sold off, the ice rink was removed, and according to the pamphlet "WBBM Radio Yesterday & Today," original building architect Andrew Rebori developed a new design for the building as a broadcast center.

At the time, the new CBS Chicago building was poised to be the network's largest enclosed studio space outside Hollywood, with over 75,000 square feet. The much larger CBS Broadcast Center on West 57th Street in New York, a former dairy depot that was actually purchased a couple of years before the Chicago building, did not go into use for studio space until 1964.

The CBS Chicago broadcast center opened in 1956 — replacing a scattered local operation with studios at the Garrick Theater at 64 W. Randolph St. and the State-Lake Theatre at 190 N. State St. — the latter of which, as it happens, is now and has long been the home of Chicago's ABC 7. The McClurg Court broadcast center later also supplanted CBS offices at the Wrigley Building.

WBBM radio operations were housed on the upper floors, while TV studios for WBBM-TV, CBS Channel 2, were housed on the ground floor.

Four years after the building opened as the Chicago broadcast operations center for CBS, Studio 1 at Channel 2 — the largest of four studios on the ground floor —would be the site where Nixon and Kennedy would meet for the very first televised presidential debate.

Frantic preparation got under way ahead of time. Producer and director Don Hewitt, who eight years later would go on to create "60 Minutes," served as the field commander for CBS at the Chicago studios. For several days, CBS executives and representatives of both candidates discussed debate rules, camera positions, lighting, and the style of chairs.

A gray background was chosen for the black-and-white broadcast, but there were discussions and debates about the type of paint and the shade. Gallons of paint were hand-carried and the set was painted again and again. It was still sticky when the candidates arrived on the evening of Sept. 26.

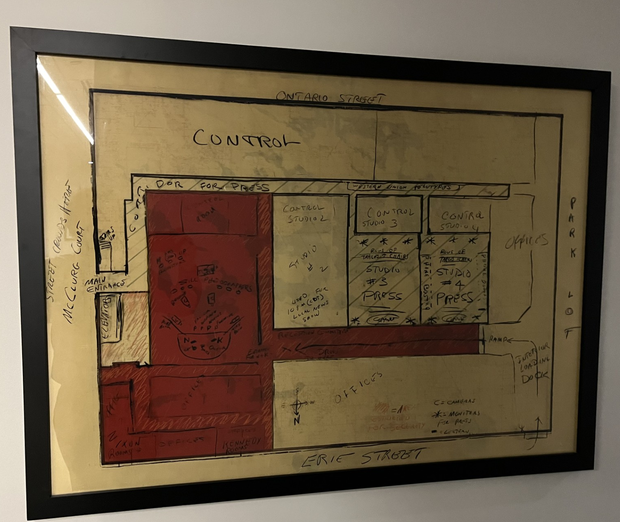

The candidates were driven into the broadcast center in late-model sedans through a back door on Erie Street, and right down a long, broad hallway that led to Studio 1. As seen in an old diagram prepared by the U.S. Secret Service and the Chicago Police Department — a replica of which CBS Chicago still has in its present building — every position was set ahead of time in Studio 1.

The candidates were in front, facing moderator Howard K. Smith and the correspondents who would ask the candidates questions — Sander Vanocur of NBC News, Charles Warren of Mutual News, Stuart Novins of CBS News and Bob Fleming of ABC News.

The Nixon and Kennedy campaigns also each had their own office space behind Studio 1. While Studio 2 was set aside for the nightly 10 o'clock news broadcasts on Channel 2, Studios 3 and 4 — farther down the hall toward the back of the building—were pressed into service for some 380 reporters who would watch the debate on closed-circuit television and type out reports in real-time.

Nixon arrived first. His car came through the Erie Street rear entrance about an hour before airtime, at 7:30 p.m. He was met right away by CBS network brass—including Chairman William S. Paley and President Frank Stanton.

Observers said Nixon seemed pale, and an aide said he had indeed turned sheet-white after suffering his knee injury and infection. Nevertheless, he came across as confident and relaxed.

Meanwhile outside the broadcast center, dozens of Kennedy supporters only glimpsed at the back door as their candidate entered in a car through that Erie Street entrance —and met with the same dignitaries and executives Nixon had.

Many remarked on how good Kennedy looked — with a tan brought about by campaigning in an open car in California. The 6-foot 1-inch Kennedy also wore a dark suit that fit better than Nixon's lighter gray suit that nearly matched the gray backdrop. Observers noted that Nixon had lost weight, and his clothes seemed baggy.

Appearances overshadow what candidates say

Before arriving, Nixon had met with a hostile labor union audience earlier in the day and had returned to the Congress Hotel in the South Loop a few minutes earlier, before going over the debate with an adviser on the way to CBS. Kennedy had made a brief campaign appearance before the same labor group, and had then spent time roleplaying the debate at the Ambassador East Hotel in the Gold Coast—with his advisers firing questions on all manner of domestic issues.

Meanwhile, Nixon's aides were worried about how he'd look on camera — with lost weight, pale skin, and stubble. The TV cameras made him look like he had a 5 o'clock shadow.

CBS offered a professional makeup artist for both candidates, but both declined such a service — despite Nixon's staff pleading with him to let the makeup artist work on him. So Nixon staffers went over to a Magnificent Mile drugstore and picked up some Lazy Shave—a product described in published reports as marketing itself as a "color-cake for between shaves."

Still, many thought Nixon looked haggard next to Kennedy.

The subjects addressed at the debate focused on domestic policy, as noted by the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. They included education, the economy, health care, labor, agriculture, and the Cold War, the library noted.

"I know what it means to be poor. I know what it means to see people who are unemployed. I know Senator Kennedy feels as deeply about these problems as I do," Nixon said to the cameras. "But our disagreement is not about the goals for America, but only about the means to reach those goals."

"I come out of the Democratic Party, which in this century has produced Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, and which supported and sustained these programs which I've discussed tonight," Kennedy told the cameras.

Nixon followed a more traditional debate style — turning and facing away from the home audience and looking at Kennedy. When not speaking, observers noticed Nixon appeared to look nervously around the studio — sometimes at CBS News President Sig Mickelson, who was serving as timekeeper. But Kennedy seemed to listen calmly and intently to Nixon when not talking, observers noted.

Meanwhile, Hewitt was in the control room directing the selection and timing of reaction shots from one candidate as the other spoke — standard procedure in television, but to the disappointment of the Nixon campaign. Nixon's campaign felt the reaction shots were too close and tight, and very unflattering — and also took issue with full-body shots that showed Nixon favoring his knee that had been injured.

Hot TV lights also had an effect. The 650-watt spotlights and studio lights caused Nixon to sweat profusely — defeating the purpose of Lazy Shave that had been applied to hide his stubble.

The Kennedy campaign, for its part, was pleased with the way its candidate appeared in the reaction shots. Kennedy got 11 reaction shots totaling 118 seconds, while Nixon got nine shots and 85 seconds.

Hewitt later said he had been told simply to call the reaction shots as he saw then, and that was what he did.

After the debate, Nixon slipped quickly out the back door. But Kennedy came out the front door of the building on the McClurg Court side — and offered reporters the understatement of the year.

"I thought it was an interesting evening," Kennedy said.

Meanwhile, Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley was very impressed with Kennedy, saying he knew a winner when he saw one.

"Terrific," Daley said. "Kennedy looked like Wilson, Truman, and Roosevelt put together."

Throngs of supporters of both Kennedy and Nixon were in the crowd in front of the CBS Chicago broadcast center after the debate. And many of those who listened to the debate on the radio, and had only the candidates' words to go on, thought Nixon had won.

But survey after survey of people who saw the debate on TV revealed the majority believed Kennedy was the victor. Those surveys also showed that among the audience of some 70 million, a huge number of undecided voters and independents decided to vote for Kennedy because of his performance in the televised debate.

Three more debates, and a lot more history at CBS Chicago's old studios

Kennedy and Nixon debated three more times before the 1960 election — in New York City; Washington, D.C.; and Los Angeles. Nixon came off better in the later debates — particularly the last on foreign policy in New York on Oct. 21.

But Kennedy won the election.

Both Democrat Lyndon B. Johnson, in 1964, and Nixon — when he successfully ran again for president in 1968 and re-election in 1972 — refused to debate their opponents. The next televised presidential debate didn't happen for 16 years, when incumbent President Gerald Ford and challenger Jimmy Carter debated in 1976. Vice presidential candidates Bob Dole and Walter Mondale also debated that year.

As to the historic Studio 1 at the old CBS Chicago broadcast center, it looked much the same when "The Great Debate" special aired 25 years after Kennedy and Nixon's visit. But it was put to other uses to great acclaim. Phil Donahue taped his "Donahue" talk show from Studio 1 before a live audience from 1982 through 1984. Chicago Tribune and Channel 2 News movie critic Gene Siskel and his Chicago Sun-Times rival, Roger Ebert, used the studio for "Siskel & Ebert" for many years too.

In 1973, the wall came down between Studio 3 and 4 at the broadcast center — the very two studios where those 380 reporters had been plugging away at their typewriters during the 1960 debate. Now double in size, this space became a massive working newsroom that was designed to double as an on-air set for the news.

The big newsroom with all its bustle was the on-air set for a famous era of Channel 2 News in the 1970s and 1980s — with such household name anchors as Walter Jacobson, Don Craig, Harry Porterfield, Lester Holt, Linda MacLennan, and of course, the very host of "The Great Debate" documentary, Bill Kurtis. Channel 2 went back to Studio 2 for its news set in the early 90s, but the big newsroom remained in use as the station's newsroom until CBS Chicago moved buildings.

And for the last several years at the old broadcast center in the 2000s, CBS 2 News — as it was known by then — was a little farther down the hall, right back in the historic Studio 1 where Nixon and Kennedy had once debated before the country.

While the 1960 Nixon-Kennedy debate was the only general-election presidential debate ever held at the McClurg Court building, it was not the only high-profile national political debate held there.

On March 13, 1992, Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton, former U.S. Sen. Paul Tsongas of Massachusetts, and former California Gov. Jerry Brown gathered at Studio 1 at the McClurg Court broadcast center for a Democratic presidential primary debate. This debate was staged by WBBM-TV CBS Channel 2, and WJBK-TV 2 in Detroit — now a Fox station, but a CBS affiliate back then.

Kurtis moderated the 1992 Democratic primary debate with Rich Fisher of WJBK 2. A digitized recording survives on the C-SPAN website.

CBS Chicago moved to its current broadcast center at 22 W. Washington St. in the fall of 2008. The old McClurg Court broadcast center was torn down, and the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab now occupies its footprint.

Watch the 1960 debate

The full Kennedy-Nixon "Great Debate" of Sept. 26, 1960, can be viewed here.