Illinois foster children are being moved repeatedly from one place to another, and traumatized

CHICAGO (CBS) -- More than 60,000 foster children have been stuck in a vicious cycle of moving from one place to another - four, 10, 20, and even more homes and institutions.

Children often suffer trauma as they constantly start over with new caregivers, communities, schools, and friends. Their paths should have been different.

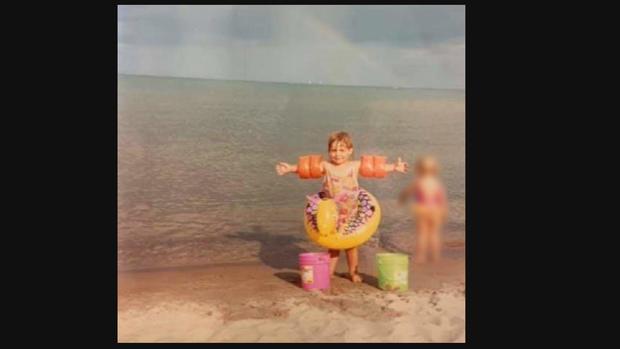

In 1991, a federal court ordered the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) to follow a consent decree. It laid out the foster care system's systemic failures and mandated reforms, including stopping the practice of moving children repeatedly. That same year, 4-year-old Mallory Stout was taken into protective DCFS custody and began her journey in foster care.

"Everything was safe. Everything was stable. Everything was good," Mallory said of her first foster home. "It was the perfect family,"

She loved being there, but her foster mother became ill. DCFS had to remove Mallory and find her a new home. That began her childhood full of turmoil.

DCFS records reveal she spent 17 years in the state child welfare system and was moved at least 67 times.

"It's a sad statistic, but it's the norm," said Mallory.

DCFS keeps data on the history of all the children in their care, including tracking how often they are moved. The CBS 2 Investigators fought more than a year for that data and finally obtained it through the Freedom of Information Act. The data are complex, with records on roughly 150,000 children. Every child's name was removed and instead assigned an identification number.

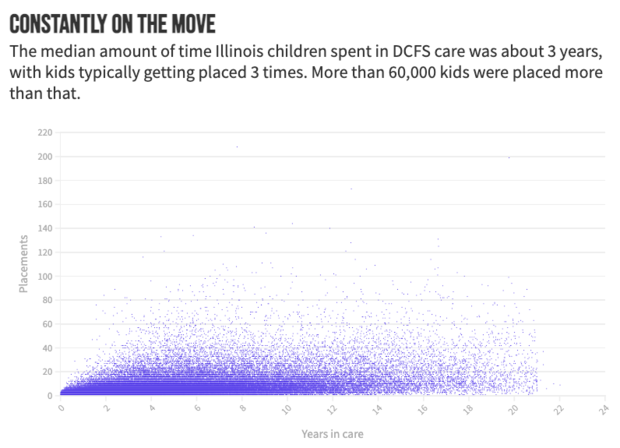

It is so complicated to understand, we created a visualization, with dots representing each child in DCFS since 2000 and how often they move.

"Each of the dots – they're a person. They're a life. There's a whole history behind each of those dots," said Mallory. "All of those are one of me."

Using this data with Mallory, we were able to find her records under identification number 1729599. We tracked all 67 times she had to pack up and move between foster homes, group homes, institutions, and hospitals.

After analyzing the data, CBS 2 found many children moved from one place to another. Nearly 62,000 kids, 41% of the children in the system, moved four times or more. About 7,000 children were placed 20 or more times.

And sadly like Mallory, 320 children moved at least 67 times. There were even 44 children moved a staggering 100 times.

"Just one day, they picked me up from school and they just dropped me in another place," said Mallory.

Often, her belongings were stuffed in garbage bags as she was shipped to different homes and facilities, and forced to change schools as she was moved across the state.

"In the middle of the night, they just dropped me off at this DCFS worker's house," Mallory said about another move.

She entered the system when she was 4, and DCFS failed to ever find her a stable home.

Dr. Michael Naylor is a psychiatry professor at the University of Illinois Chicago. He runs mental health programs through a DCFS contract.

"There's this really horrific kind of cycle that goes on," said Naylor. "If you don't intervene, you can have these kids with 20, 30 different placements."

He says multiple placement disruptions cause huge trauma.

"The ones that we see, all of them are carrying scars that they're going to be carrying with them the rest of their lives," said Naylor.

"I am 36 years old and, I have nothing," said Mallory about the lifelong mark of all the moves made on her. "Being in care... slowly through every placement, something more was gone – and at the end, you have nothing."

Mallory was part of a group of 14 adults who grew up in DCFS care, and spoke out in 2019 to try and stop DCFS practices they say are destructive. Carnell Brown was part of that group, and knows the trauma that comes with being frequently moved.

Carnell says DCFS repeatedly had him pack up and move to different places.

"I say about 30," he said. "I really moved around a lot."

Happening throughout his childhood, Carnell said it impacted his relationships.

"Try not to get too attached to people," said Carnell who lost friendships through the years. "A lot of friends – I have no one that I can really call my friend."

"I think central to all of the difficulties here are the disruptions in relationships that these kids have," said Dr. Naylor about the department often moving children.

Naylor said a significant problem is DCFS's inability to have enough placements to match children to.

"There are too few foster homes. There's too few specialized foster homes and therapeutic foster homes. There's too few group homes and residential facilities," Naylor said.

Mallory and Carnell both said their bad placements were followed by neglect, and even more abuse. The system that was supposed to protect them - failed.

"Oh, yes. Yes, plenty of times," Carnell said when asked if he was abused as a foster child.

"The amount of abuse I received in the system does not equal what I received at home," said Mallory.

Both say none of their abusers were ever held accountable.

In November 2022, a CBS 2 investigation found the vast majority of abuse and neglect allegations against foster parents are closed without findings against them. Using DCFS foster parent abuse data dating back to 2016, we were able to reveal nine out of every 10 abuse or neglect allegations were closed by the child welfare agency as "unfounded."

CBS 2 also found DCFS failing to track every time they contacted police when there was neglect or abuse. This led Illinois State Rep. Lakesia Collins (D-Chicago) to work on new legislation. She spent years as a foster child, and said no one held her foster parent accountable either.

"She beat me up right in front of other kids in the house," said Collins. "Police were not notified. The caseworker never followed up with me. It's like it never happened."

Collins, the newly elected leader of the Illinois Legislative Black Caucus, wants to create a law requiring DCFS to track its calls to police and the outcomes too.

Mallory still struggles with the years of abuse she suffered in DCFS. In one home, she was severely punished for bed wetting.

"They removed my bed and made me sleep on the bars of the bunk bed," said Mallory.

Then she was beaten, and a special friendship bracelet was ripped off her ankle. It was made by a friend Mallory had to leave during one of her 67 moves. The bracelet meant so much. Thinking about it being ripped away brought her to tears.

Something so small meant so much to her.

"But basically, it's the cost of being in care," said Mallory.

She thought she would be safer in the child welfare system than she was at home.

"I had bruises. I had lots of bruises and scars. I still have some scars from being a child," said Mallory about her life before DCFS. "I was starved. I was locked in a bathroom. I was held in a bathtub with a baby gate over it. I was essentially caged, and treated like an animal."

"I repeatedly would eat out of the garbage can at my daycare, because I wasn't getting enough at home," Mallory continued.

After that, she said someone from the school called DCFS – and that's when she was removed from her home.

Mallory was hospitalized when she was 4, according to medical records. Those records revealed evidence of abuse and neglect, such as bruises. She even told staff she was shot by a BB gun.

But Mallory says her path through the child welfare system was even worse. She suffered abuse throughout her childhood in DCFS and got stuck in the system - languishing until she was old enough to age out.

An analysis of the DCFS data revealed many children spending years in the system. More than a third of the children – roughly 53,000 – spent four or more years in DCFS. There were nearly 10,000 children who spent 10 years or longer in DCFS.

The data show children typically spend three years in DCFS care, across all types of placements. Nationally, the median time spent in care is much lower – about 15 months – according to data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The federal agency tracked foster children in care in the U.S. as of Sept. 2021.

National data also shows 6% of children spent five or more years in child welfare systems. In Illinois, 26% of children were in the system that long. Illinois ranked last nationally in reunifying families within one year. It ranked second-to-last nationally in getting children adopted and out of the system within two years.

An HHS spokesman said there's no national tracking of how often foster children are moved.

Like Mallory, Carnell moved often and languished in DCFS until he was old enough to age out. He was in for 15 years, and he's not alone: 2,542 children spent all those years in care too.

"It does a lot of damage," said Carnell.

He and Mallory each are parents now. Their time in care haunts them, and they both have a real fear of their children being taken into the system. They also worry about all the other children in the system now, and hope speaking out will make a difference.

"Accountability – lots of accountability and change," said Mallory, reflecting what they each want to see happen with DCFS.

DCFS in a statement says:

"DCFS remains laser focused on continued improvement with robust efforts to expand available placements, recruit new foster families, and improve wraparound services provided to children and families."

How we did this:

CBS 2 obtained placement data from DCFS that showed more than 1.1 million recorded placements of children in care since 2000.

We removed all records where placements were one day or less. We removed all placements that were categorized as: unknown, unknown whereabouts, runaways, unauthorized placements, abducted and deceased. Data recording job and college placements were also removed.

The refined data resulted in roughly 806,000 placements spanning 22 years and about 150,000 children.

Placements were grouped by each child's unique anonymized ID to get a count of placement per child. The days spent in each placement were added together for each child ID, resulting in a total days and years spent in DCFS care via placements.

The median time spent in care was 2.9 years, with a mean of 3.8 years.