Durkin: Breaking Down The Bears' 'Switched Verticals'

By Dan Durkin-

(CBS) When you consider he had just more than eight months to orchestrate a complete overhaul on offense, Marc Trestman's pioneer run as an NFL head coach was impressive.

Meshing together five new coaches, five new starters, new terminology, protection schemes and base concepts requires extensive knowledge, leadership, trust and clear communication. The offensive output demonstrated Trestman excels in all these categories.

From 2012 to 2013, the Bears offense jumped from 29th in passing yards to fifth, 28th in total yards to eighth and became the league's second-highest scoring team.

So how did Trestman do it?

Synergy, talent and deception.

During Trestman's introductory press conference, general manager Phil Emery repeatedly used the word synergy. Given the concerted effort to bring in an offensive staff with extensive NFL experience, completely revamp the offensive line and acquire a real tight end, Trestman and Emery were harmonious in their vision of what the Bears needed to do in order to become a modern NFL offense.

In the meeting room and on the practice field, Trestman devised a bevy of personnel groupings and formations to give defenses a variety of packages to prepare for, but at its core his offense revolved around some base concepts that the Bears executed with great success.

The first concept we will break down is called "switched vertical."

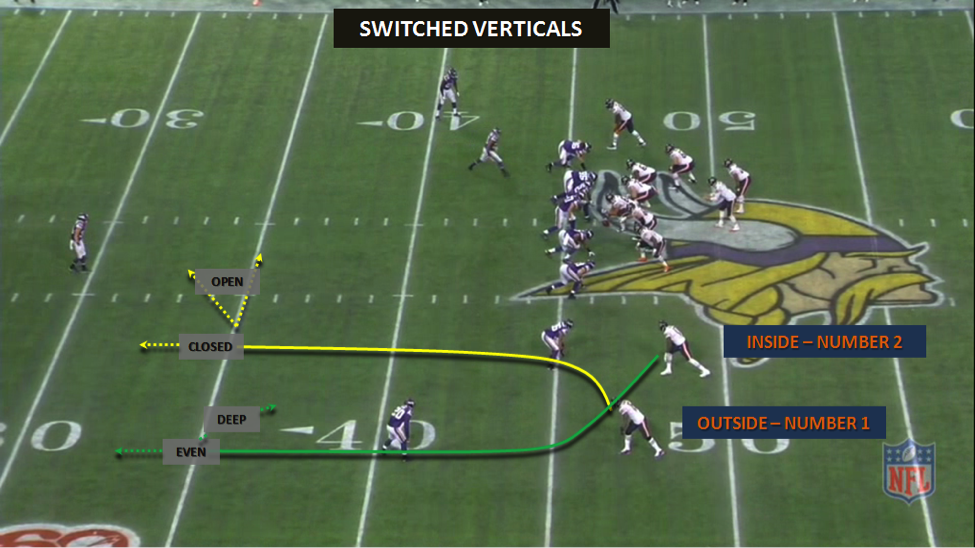

This is run from a two-receiver set in which the outside (No. 1) and inside (No. 2) receivers switch their releases off the line of scrimmage. Consequently, the inside receiver becomes the No. 1 -- sometimes referred to as the "final 1" -- and the outside receiver becomes the No. 2.

This concept is effective against both zone and man coverage. Against zone, it puts the sideline defender in coverage conflict. Against man, the receivers can "rub" off a defender to get a free release.

For the outside receiver, he performs an inside streak read, which means scanning the middle of the field. If the defense is in Cover-2, the middle of the field is considered open, and he will run a post or a dig. If it is Cover-3 or Cover-1 (man free), it is considered closed and he will push the vertical seam.

For the inside receiver, he releases on a wheel route and scans the deep outside-third of the field. If the cornerback is trailing or even with him in man coverage, he will continue on a vertical route. If the cornerback is playing deep, he will hook his route back to the quarterback on a curl.

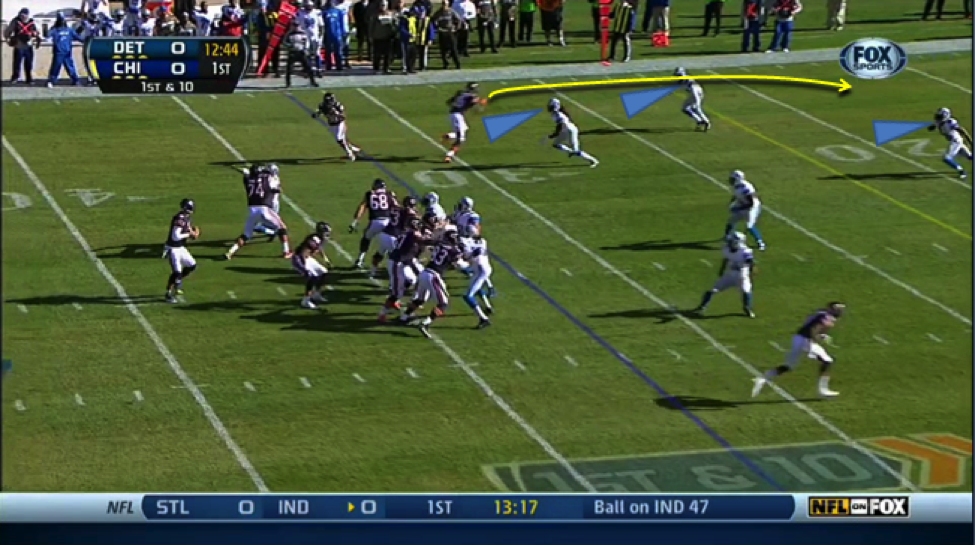

Here's a visual to help illustrate the receivers, their releases and subsequent reads.

In addition to spying the quarterback, deep safeties read a receiver's release off the line of scrimmage to help simplify their keys. Depending on the receivers' splits and location on the field, the full route tree may not be available to them at the top of their route in the move area. By switching releases, safeties are forced to re-think their rules on the fly, which can add conflict and confusion.

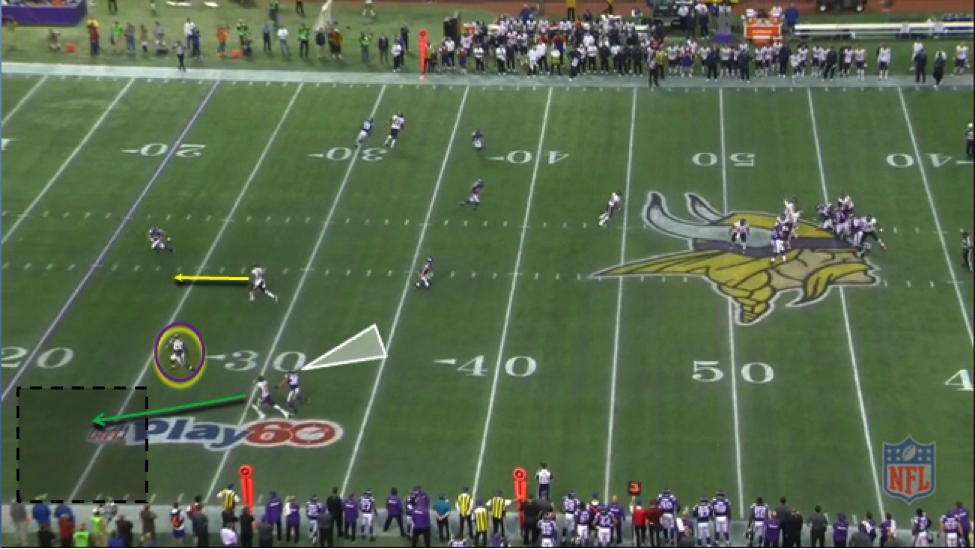

Here's an example from the Bears-Vikings game in Chicago. Trailing 30-24, the Bears have the ball facing third-and-10 at the Vikings' 16-yard line with 16 seconds remaining in the game. The Bears come out in 11 personnel in a 2-by-2 set. Tight end Martellus Bennett slightly walked out from the wing to the slot, prompting linebacker Chad Greenway to walk out and match.

The Vikings respond with nickel (five-defensive back) personnel, in a single-high safety look, with linebacker Erin Henderson (black arrow) and safety Jamarca Sanford (white arrow) showing blitz.

Pre-snap, Vikings right cornerback Chris Cook (circled in purple) is signaling to free safety Harrison Smith to come to his side of the field. Smith is shaded toward Brandon Marshall and Alshon Jeffery (three defensive backs over two receivers), showing the Vikings are rolling deep help to Marshall's side of the field, so they're already slightly misaligned pre-snap.

The Vikings drop back into a Cover-3 look –- not an ideal call at this area of the field –- and Cook is left in limbo. Both receivers push vertically, and Cook opens his hips to match Earl Bennett's release on the vertical seam, leaving Martellus Bennett open to work the back-side vertical.

Quarterback Jay Cutler reads Cook's leverage and threads a back-shoulder bullet to the pylon, which Bennett secures for the game-winning touchdown.

By switching the releases this close to the end zone, the Bears put Cook in conflict both pre-snap and post-snap. It was a savvy twist by Trestman on a game-winning play call.

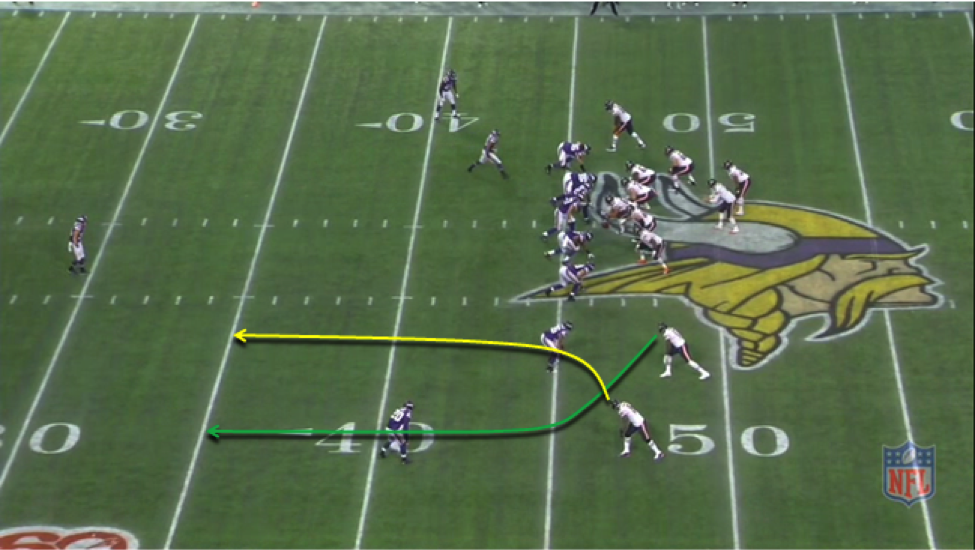

Here's another example from the Bears-Vikings game in Minnesota. At the Vikings' 47-yard line, the Bears come out in 12 personnel, with Marshall as the outside and Jeffery as the inside receiver.

The Vikings respond with nickel personnel in a single-high safety look, with both their linebackers in a "mug" blitz look. Again at right cornerback, Chris Cook is playing off coverage, and safety Robert Blanton is lined up in press coverage over Jeffery.

The Vikings don't blitz and drop back into Cover-3 (three deep, four underneath). Once again, the Bears put Cook in limbo, and once again, Cook opens his hips to the inside, leaving Jeffery free to work the back-side vertical. Blanton –- the underneath curl defender –- turns his shoulders to read the quarterback, which isn't how the technique is taught.

Yes, Blanton isn't responsible for the deep third (Cook is), but by turning his shoulders –- instead of just turning his head –- it allows Jeffery to separate and provides quarterback Josh McCown a window to drop the ball into.

Given the distance of this throw, the defensive backs do have time to adjust and make a play on the ball, but Jeffery high points the ball on a spectacular touchdown reception.

Same concept, different personnel grouping, same result.

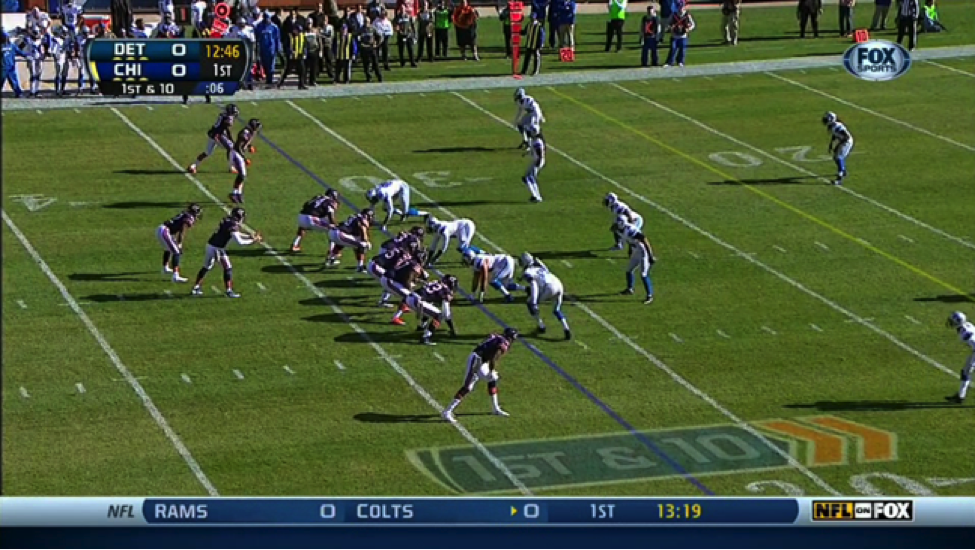

The Bears also built variants, known too as "constraint" plays, off of their switched verticals concept. For example, take this play from the Bears-Lions game in Chicago.

The Bears come out in 11 personnel, and the Lions respond with their nickel package with three defensive backs over the two-wide receiver side of the field.

Earl Bennett releases on a bubble screen, getting all three defensive backs to jump. Most importantly, the Bears lure the free safety to pursue downhill, which allows Brandon Marshall to switch his release and draw single coverage up the sideline.

Marshall pushes the vertical route, but with the safety making a misread on the bubble screen, the middle of the field is open, so he bends his route into a skinny post. Cutler delivers a strike for a Bears touchdown.

The switched release has been around since the run-and-shoot days, allowing quarterbacks and wide receivers to adjust to coverage as it unfolds. But in order for it to succeed, there has to be a clear understanding of how to adjust. Seeing how successful the Bears were with this concept in a short period of time is encouraging for the future success of the offense.

Last year in Bourbonnais, Cutler said it would take three years to master Trestman's scheme. Judging by the results and success he and McCown had in the first year, he may have been off in his estimate.

Follow Dan on Twitter: @djdurkin