The Chicago Police Department's secretive dealings with confidential informants and bad tips and wrong raids

CHICAGO (CBS) -- The Chicago Police Department's program for using confidential and registered informants is shrouded in secrecy and is lacking full accountability.

This important crime-fighting tool helps officers get tips on where to find illegal guns and drugs. But we found officers often simply rely on the word of informants and fail to do the police work required to verify the tips. This has led to, at least, dozens of search warrants being executed at the homes of innocent people.

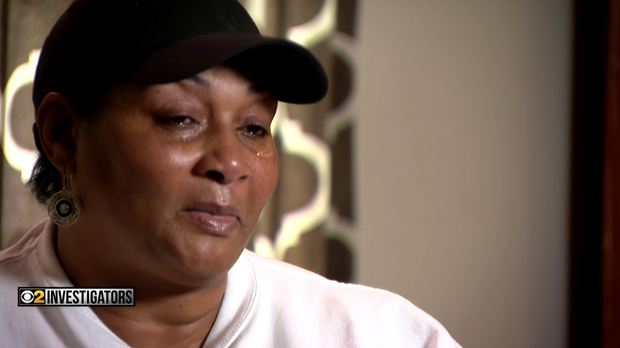

Anjanette Young and Cynthia Eason are just two of the many wrong raid victims who want to know more about the informants police used in their cases. Those names will never be released to them nor will they find out if there were consequences for the bad tips.

Informant names are kept confidential because of the potential danger they could face. The Chicago Police Department has been fighting to keep other records from becoming available to the public too. Those include taxpayer money spent on informants and the full set of rules police have to follow while working with informants.

In Cynthia Eason's case, new details have come out about the informant whose tip led SWAT and the Area South Gun Team to wrongly raid her daughter's home on a hot August day in 2018. The family's home was ransacked. Guns were pointed, even at the children.

Chicago Police Officer Michael Higgins was the affiant who worked with the informant in Eason's case and obtained the search warrant. He had to testify in a deposition after the family filed a lawsuit.

"We know the fact that children are involved in something, like this is terrible. They don't need to see this. But we have a job to do," said Higgins.

While under oath, Higgins answered questions about his use of a paid, Registered Confidential Informant (RCI). Higgins said the RCI had pending criminal charges during the three years the two worked together. The charges included having a suspended license, failure to pay child support and fraud.

It is not a secret that police cut deals with criminals in order to catch other criminals. Informants often get paid or some other benefit for their tips.

What we don't know is how much taxpayer money is used to pay informants. And whether the confidential informant system is even working.

The informant did not mention anyone in the Eason family, but gave police an address where they could find a gang member and a semi-automatic handgun. It was the wrong house.

The botched case turned into a federal lawsuit. Legal fees for depositions of the officers and victims along with the cost of hiring private attorneys has cost taxpayers, so far, more than $330,000. We found, since 2015, taxpayers have spent nearly $8 Million in legal fees and settlements for similar cases of bad raids that began with bad informant tips police failed to verify.

"I don't think they care," said Eason about the pain wrongly targeted families suffer.

For months we've tried to find out how much the Chicago Police Department is spending on this crime fighting program. We also want report just how many crimes they've been able to solve because of confidential informants. We will continue to fight to get this information.

Jim Trainum is a former homicide detective from Washington, D.C, who also is police practices consultant. He said taxpayers have the right to know how their money is being spent by the police department.

"I absolutely do think that they have a right to know," said Trainum. "Even just, at least, general terms, to know if there's a huge amount of money but there's really nothing to show for it. Or if there's a lot of money going into a program that's giving very questionable results."

Our years-long investigation into wrong raids and informants included numerous Freedom of Information Act requests for data and records. As the Chicago Police Department repeatedly refused to turn over public records, we filed appeals with the office of Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul.

"We have to be voices that support transparency," said Raoul.

His office is in charge of making sure government agencies, including the Chicago Police Department, are following the law when it comes to public records, or Freedom of Information Act requests. This past July, his office ordered CPD to turn over police policies related to paying informants which the department refused to release under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

When asked, the Illinois Attorney General said the amount of money being spent on informants should be something we should be able to get through FOIA.

"That seems like something that shouldn't fall within an exemption," said Raoul.

Records the police department turned over following the IL AG's office ruling, have a lot of information redacted. Big chunks of black covering information the department doesn't want you to see.

"Anytime that you have secrecy, and that you don't have somebody from the outside looking in to make sure everything is on the up and up - I mean, that just makes it so ripe for abuse," said Trainum. "And not only like criminal type abuse, but also the use of the way the information is collected. People have a tendency to take shortcuts."

Shortcuts on the police work to get the warrants has led to mounting lawsuits. As is the case involving Officer Michael Higgins. During his deposition he said he didn't know how much the informant was paid. But he was aware his informant needed money, desperately.

"I know if he can't make his child support, he'll end up getting a warrant put out and arrested," said Higgins during his deposition.

The child support violations led to his informant's license being suspended repeatedly and jail time. Higgins said another law enforcement agent even worked out a special payment plan so the informant could avoid jail.

"When she pays him, she has, waits, so she makes sure he pays the child support," said Higgins.

Trainum questions this tactic, "So there is an increased amount of pressure on him to to deliver something. And when you're under pressure, you sometimes do things you shouldn't do."

Tonight the Chicago Police Department sent us a statement saying they are committed to transparency and accountability. But they didn't send us the records. We will keep fighting to get you the information about your money and this program.

Chicago Police Department statement:

The Chicago Police Department is committed to transparency and accountability. We will continue to be transparent with information, while balancing confidentiality in the interest of public safety.