Chicago Hauntings: The Horrors Of The Iroquois Theater Fire That Killed 602 People Downtown In 1903, And Stories About Ghosts Left Behind

CHICAGO (CBS) -- "Five hundred and seventy-one lives were destroyed by fire in the Iroquois Theater in the fifteen minutes between 3:15 and 3:30 o'clock yesterday afternoon," reads a Chicago Tribune article from Thursday, Dec. 31, 1903. "Of the dead, less than 100 were identified last night. Of the unidentified nearly all were so badly burned that recognition was impossible. Only by trinkets and burned scraps of wearing apparel will the bodies of hundreds be made known to their families."

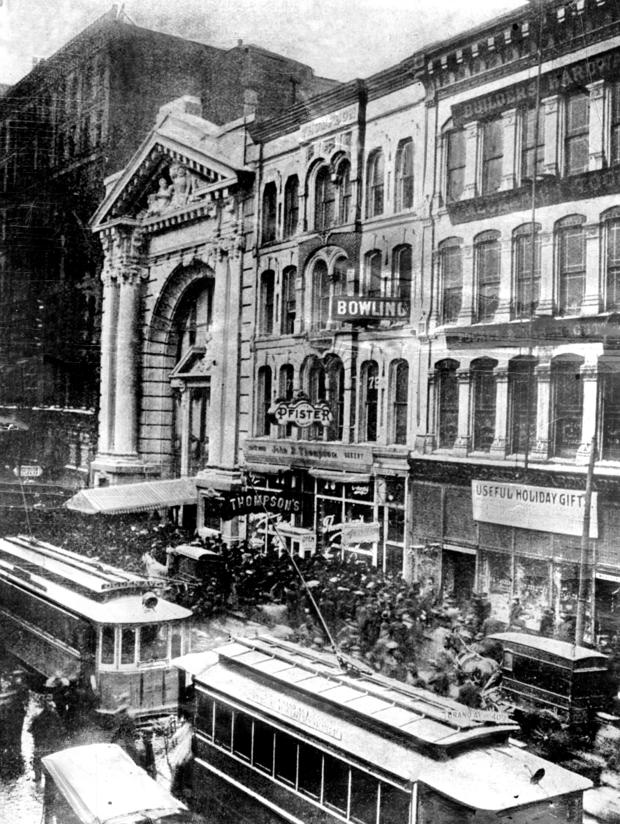

That number was not final. A total of 602 patrons died in the fire at the Iroquois Theater at 24-28 W. Randolph St. downtown that chilly Wednesday, Dec. 30.

By contrast, an estimated 300 people died in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

At the time of the fire, the Iroquois Theater had only been open six weeks. As the Encyclopedia of Chicago tells us, theaters had been burning down throughout the 19th century, only to be rebuilt and then burn down again.

"From the first Chicago theater, built by John Blake Rice in 1847 and rebuilt following a fire three years later, through the Great Fire of 1871 and until the end of the century, fire kept Chicago's theaters in a state of constant regeneration not unlike the surrounding Illinois prairie," the encyclopedia says.

Tony Szabelski of Chicago Hauntings Ghost Tours notes this was a problem not just in Chicago, but around the country. With that in mind, the ornate new Iroquois was billed as "absolutely fireproof."

Szabelski notes the Iroquois was set to open before the holiday season in 1903, because the owners thought it would likely draw more revenue than opening in the dead of winter in January or February. This was despite the fact that construction had been behind schedule.

Thus, in the rush to open, Smithsonian Magazine reports the city only underwent a "cursory" safety inspection before it opened. It was never proven in court that any corruption was involved, but the magazine emphasized that "indifference of city officials to known violations" was a contributing factor.

This was also despite the fact that Mayor Carter Harrison IV had ordered a safety review of all theaters a matter of months earlier, but city officials were not enthusiastic about it and little was done, the magazine reported.

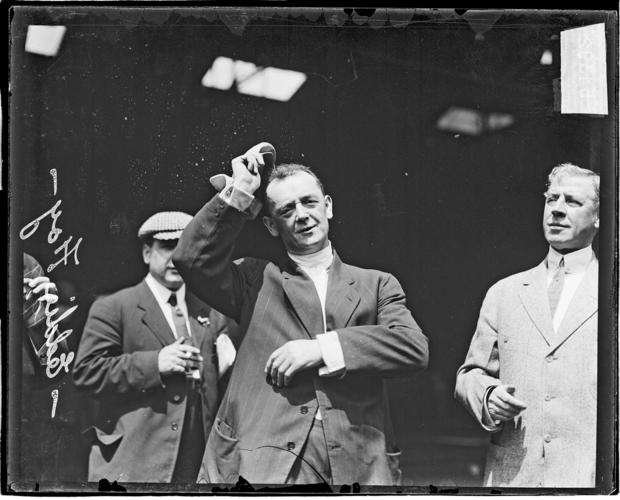

Things went smoothly for the opening six weeks or so. But that all changed horrifically on Dec. 30, during an afternoon matinee performance of "Mr. Blue Beard" – a children's comedy starring a well-known comedian named Eddie Foy.

The play was based on a French folktale about a wealthy nobleman who has lured a succession of women into marriage and gone on to murder them and a new wife, Fatima, who tries to avoid such a fate. This tale that separately inspired the moniker "Bluebeard Murderer" for Chicago serial killer Johann Otto Hoch.

Yes, we did say it was a children's comedy. Reports say it was made family-friendly by having the murdered wives come back to life at the end. Adam Selzer reproduced a quote from the Chicago Tribune suggesting that critics were not enthused with the play:

"Of story, there is little or none – nobody expected there would be any, and nobody cared because there was none. There is the usual loving couple who have hard times getting their love affairs to running smoothly, there is the usual wicked persecutor of the maiden in this enamored couple – in this case he is Mr. Blue Beard – and there is, of course, the regulation good fairy and the magic horn which calls her to the hero's aid….the music of the piece of hopelessly common, save bits here and there which are flinched from the classics."

On that Dec. 30, the first act of the play went fine. But around 3:20 p.m. during the second act – while the Chicago Tribune reports ballerinas and blue and gold were dancing on the stage to a number called, "Let Us Swear It by the Pale Moonlight" (hear a piano version here) – a flash was seen near an electric spotlight, and flames spread across a drape and ended up igniting an area containing flammable oil-painted backdrops hanging from oiled ropes.

Szabelski notes at first, no one panicked – as they had been told the theater was fireproof and even had a fireproof curtain made of asbestos and wood pulp going down the center. Foy even took to the stage and implored people not to worry – saying people could exit calmly if it became necessary and even singing them a little song.

But when the fire curtain came down, it snagged and failed to make it all the way. Even attempts to pull it down manually didn't work. At that point, spectators – many of them women and children – started to panic as they made a mad rush for the doors. Meanwhile, the cast and crew opened a set of outside doors – which let in air that caused a backdraft effect and sent a ball of fire into the theater.

"The fire leaped from the stage as if from a furnace door. The draft from the opened stage exits behind drove it across the auditorium and upward to the galleries. Over a carpet of the dead it forced its own way through the chimney of the alley doors on the galleries," reads the Tribune account from the following day. "The newest theater in Chicago, the playhouse declared to be fireproof from dressing rooms to capstone, burned till the stage was a steel skeleton and its wrecked interior a charnel house."

A more contemporary Tribune report said even the fire curtain "burned like a rag."

Szabelski notes one of the reasons the theater was supposed to be fireproof was because it had more fire exit doors than any other theater in the world – 30 in all. But initially, nobody could find the exit doors because there was no marking or lighting to designate them. Szabelski says the theater owners thought such displays would be distracting from the show.

Even when people found the exit doors, most of them turned out to be locked with huge deadbolt locks – as the owners didn't want people to sneak in and get a free show.

Up in the balcony, people exited through the doors leading to the fire escapes, but roughly 120 people ended up falling to their deaths from fire escapes onto the alley below. The alley between Lake and Randolph streets going east from State Street – officially the first of several disjointed pieces of a minor street called Couch Place – was called "Death's Alley" in the newspapers the very next day.

The reason so many people fell to their deaths is because the fire escapes were not finished, and patrons did not realize there was not enough space to hold them all until it was too late. Reports say some workers cleaning at the Northwestern University building across the alley lowered planks to get some people across the alley – and a few made it, but many did not.

People also could not get out of the back end of the building, Szabelski points out. They ran toward the front end under the marquee where they came in – but even then, they had a hard time getting out. Typically today, one would expect an exit door to have a bar on it with which one would push the door outward – but the entry and exit doors for the Iroquois pushed inward.

Meanwhile, the Fire Department was nowhere to be seen, because no alarm had been pulled to send them. A stagehand finally pulled a manual fire alarm at Randolph and Dearborn streets, because there was no fire alarm connected in the building. By the time firefighters arrived, it was too late – they opened the front doors to find an eerie silence and a sight of dead bodies stacked up in rows.

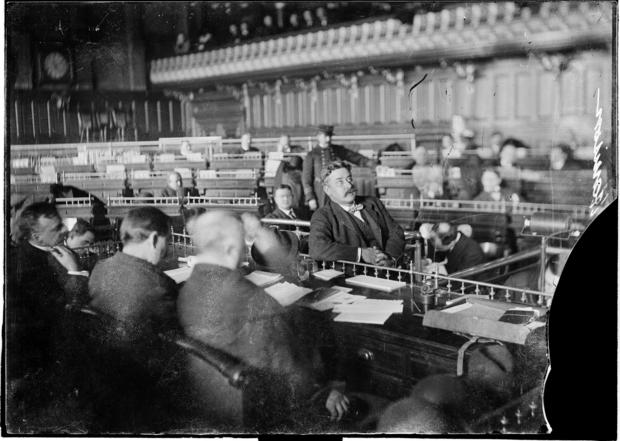

A Library of Congress research guide notes that on New Year's Day 1904, 19 theaters, opera houses, and museums were ordered shuttered because of fire code violations – and soon afterward, Mayor Harrison ordered all theaters closed for a fire code compliance review.

Meanwhile, multiple reports say charges were brought against the theater owner and manager, and several city officials including Mayor Harrison himself – on the grounds that he was aware of the theater's code violations. Mayor Harrison was not indicted, though some of the others were. However, according to the blog Memories of the Prairie, most of the charges were thrown out – except for those against a saloon owner who pickpocketed dead bodies.

The fire remains the single deadliest single building fire in terms of loss of life in American history, and the single deadliest theater fire in the world, Szabelski notes.

As to the Iroquois Theater building, it did not actually burn down. In fact, it went on not too long afterward to reopen as the Colonial Theater, and was only torn down in 1925 to make way for the present building on the site. That building was originally the Oriental Theatre – which opened in 1926 as a movie palace, but also hosted stars such as The Three Stooges, Judy Garland, Al Jolson, and Duke Ellington.

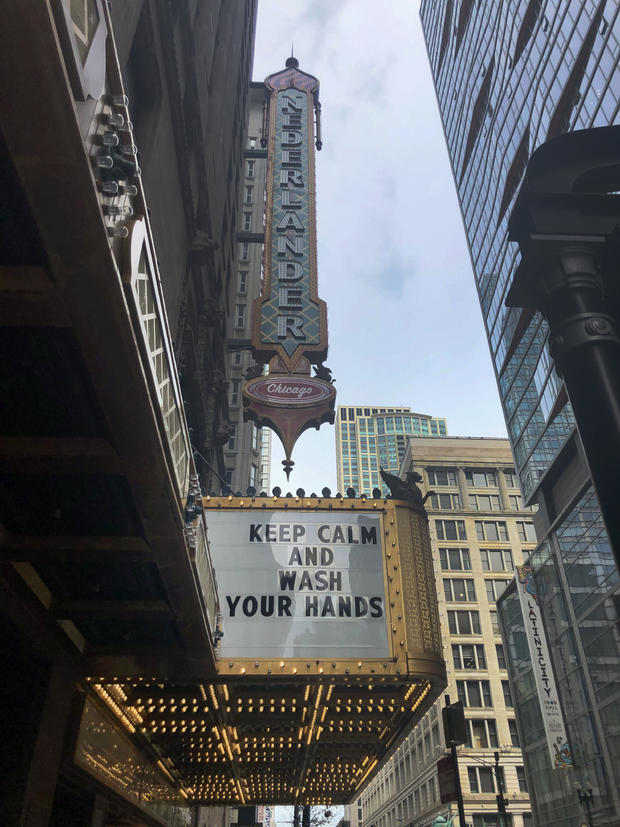

The theater closed in 1981, but was subsequently restored and reopened in 1998 as the Ford Center for the Performing Arts at the Oriental Theatre, with "Ragtime" as the first performance. In 2019, the name was changed from the Oriental Theatre to the Nederlander Theatre, in honor of Broadway theatre owner and producer James M. Nederlander.

Szabelski reports some ghosts evoking the Iroquois have been reported in and around the Nederlander for many years. Casts and crews report that while they're rehearsing onstage, they will look up in the balcony and see shadow figures moving around. People also reported seeing apparitions of strangers on the back stairs wearing period wear from the turn of the last century.

The Nederlander – back when it was still the Ford Center for the Performing Arts at the Oriental – also played host to a record-breaking run of the show "Wicked". Onetime cast member Ana Gasteyer, a "Saturday Night Live" alumna, appeared on the show "Celebrity Ghost Stories" to talk about what she thought were experiences with the paranormal.

Gasteyer said what is now the Nederlander was steeped in glamour, but also described a dingy, dusty, and drafty quality. She described the alley behind it – Death's Alley from the Iroquois fire – as a place that "always had the gloomiest, darkest, most dismal – it was a terrible alley. It really was. It felt terrible."

In 2005 and 2006, Gasteyer played Elphaba, the Wicked Witch of the West, in "Wicked" at the then-Oriental. At the end of Act I, she notes in "Celebrity Ghost Stories," there is a climactic moment in which the witch is learning to fly, and a huge amount of smoke and fog envelops the auditorium as the orchestra soars.

While "flying," Gasteyer reported she would look out to the sides and see people in the wings. She said there were a lot of stagehands on the production – but this was more people than should have been there. She said they were gathered "almost like families; gatherings of people that were together" – but then once she landed, there wouldn't be anybody there.

She also reported hustling down the hallways between from her dressing room in her witch dress with no one around, and reported first hearing a child's voice. She said she turned a corner and found a woman at the end of the hall near the stairwell. The woman was with two children – a boy and a girl. All were in turn-of-the-last-century period dress.

"My first kind of instinct was just kind of a backstage instinct – oh, there's another actor. I nodded. (The woman) was very stoic. She didn't smile. She nodded back," Gasteyer said on the program.

When she turned another corner, the woman and children were gone, Gasteyer said. And she said when she asked her dresser about it, the dresser noted that Dec. 30 was coming up and suggested they were ghosts from the Iroquois fire.

Back in Death's Alley, Szabelski says people tend to encounter things and take lots of strange pictures – especially along the back walls. Szabelski also said one friend who claims to have psychic abilities – and who came on a lot of ghost hunting tours with him – said he feels too much energy in that alley and would not even walk down it.

Nearby buildings are also involved when it comes to stories about ghosts that might be connected to the Iroquois fire. Szabelski notes that the Marshall Field's department store opened its eighth floor for use as a triage hospital and morgue for fire victims.

The store has been known as Macy's on State Street since 2006, and Szabelski says there have been subsequent reports of hauntings on the eighth floor. He reported for instance that when the new employee lockers were on that floor, a lot of new employees reported experiencing "weird things." The lockers were later moved elsewhere, Szabelski reported.

Finally, the one positive outcome from the fire is that it indeed did change fire code laws. All public buildings now must have clearly marked fire exit doors that can be open easily, as well as operational fire alarms and sprinkler systems. Doors also must open outward instead of inward, and curtains that actually slowed the progress of fire were installed. New building standards for theaters were even instituted as far away as New York because of the Iroquois fire.

Szabelski notes that is really the only good that come of this horrific tragedy.

Video produced by Blake Tyson. Written story by Adam Harrington.