CeaseFire Strives To Stop Violence On Chicago Streets

CHICAGO (CBS) -- The summer season just started, and it's already been a violent one in Chicago.

Twenty-six people were shot in a short period of time over Memorial Day weekend, and seven of them died.

CBS 2's Bill Kurtis has been following a group that works tirelessly to prevent violence. Such a mission is needed in particular when last year, while 499 troops were killed in Afghanistan, 435 Chicagoans were killed just a few miles from downtown Chicago – many of them just children.

Family members of the victims of violence tell their stories in a video.

"One of my sons was killed eight years ago," a woman said. "The other was killed, three, four months ago."

"I lost somebody every year, at least every year," a young woman said. "People I look up to, I always lose them."

"My daughter was killed while jumping rope," a third woman said.

Acts of violence unknown to us – and some well-known, like the brutal beating of Fenger High School honor student Derrion Albert in 2009 – is learned behavior, according to Dr. Gary Slutkin at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

In some communities, violence is the social norm, and is expected. Left untreated and encouraged by peer pressure, Slutkin says, violence spreads like a plague.

"Where did this violence come from? Are the teachers going to change it?" Slutkin asked a crowd of teens. "Do you think that the police are going to change it? Do you think that your parents are going to be able to change it?"

The group answered "no" to every question.

Fighting epidemics with the World Health Organization for more than 10 years, Slutkin learned that throwing antibiotics at, say, cholera, will do nothing if people keep returning to the same river to drink. He is trying to stop Chicago's children from going to the river of learned behavior, through his program, CeaseFire.

He drew a comparison for how social norms can change.

"It used to be that it was normal to smoke in a room like this," Slutkin told students in an assembly hall, "even though, it's not normal now. So, how did that happen?"

Tio Hardiman is director of CeaseFire. He leads a tough weekly roundtable of CeaseFire's salaried workers.

"From January 2010 to December 15, we've mediated about 494 conflicts," told the roundtable.

One of the CeaseFire workers talked about his own background.

"I was incarcerated when I was young," said Alfonso Prader. "I was on a gallery trying to holler with five or more hundred people trying to get information to another guy to get me some cigarettes. So I holler for him. And I holler one morning when I woke up and my voice was gone."

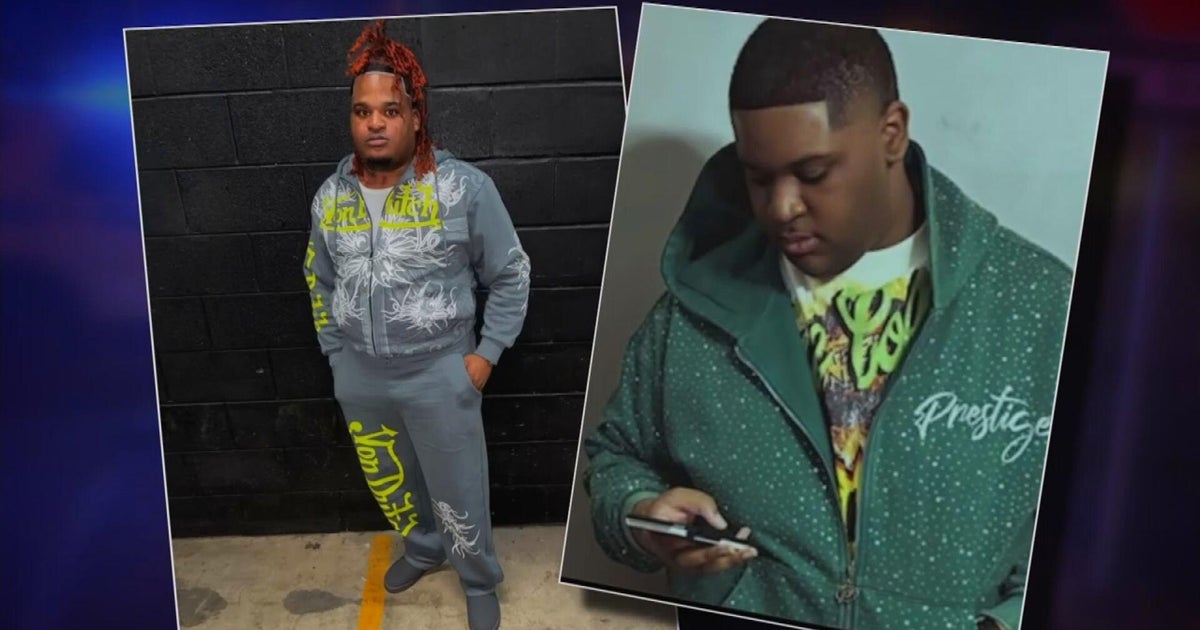

Many gang members who served time make up the CeaseFire staff. They're called "violence interrupters."

They talk about their experiences trying to stop violence at the roundtable meeting.

"They retaliated but it didn't go as far as them shooting at people's houses," one interrupter said.

"They shot her son over his $1,000 jacket," said another interrupter, Fred Seaton, addressing a victim's mother. "I know you love supporting your child, but he needs to not be walking up the street at 10, 11 o'clock at night with $1,000 on his back."

"That's not what happened," the mother said.

Results at CeaseFire are impressive. Studies show a drop in homicides as dramatic as 80 percent in the Austin and Humboldt Park areas last year.

Also impressive in our budget-strapped city are these statistics – for each of the 1,845 shootings reported last year, medical costs averaged over $45,000, and 96 percent of that comes from government funds.

If you do the math, that's $79,704,000, paid by the government, last year alone, right here in Chicago.

That, of course, is a lot of money when our schools and government are strapped for cash.

But what about the goal? How do you stop the violence, if it's been going on for a long time?

If you believe CeaseFire is the answer, it's about stopping the shooting and the violence before it happens, and through that changing behavior.