Bonds' Perjury Trial Starts Monday

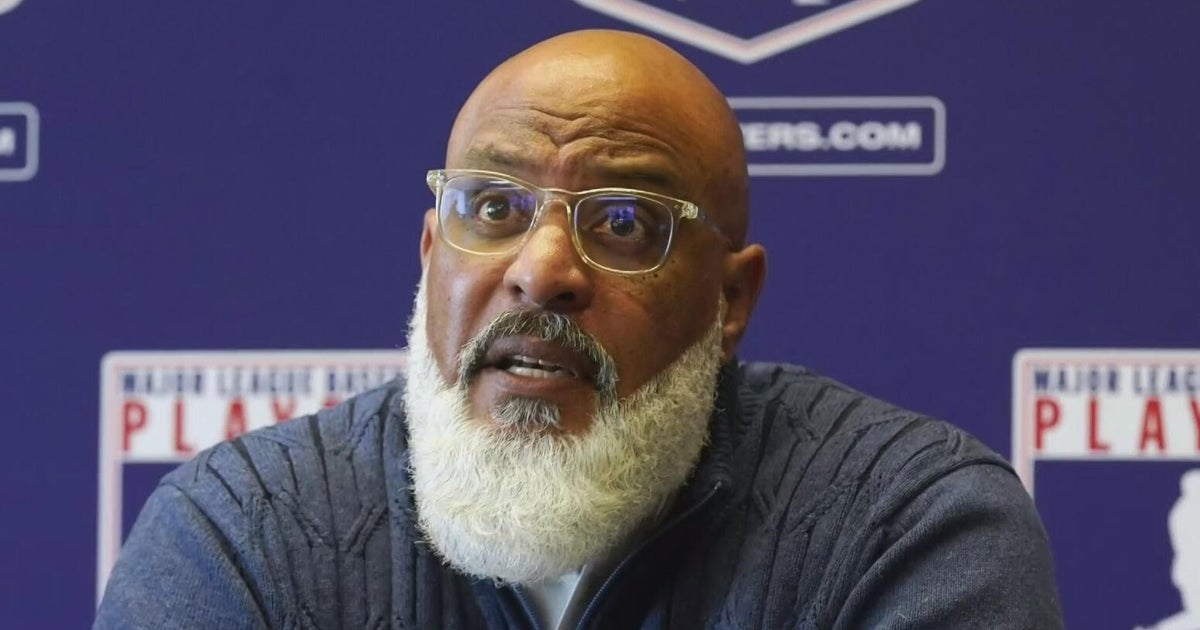

Barry Bonds finished his career with some impressive achievements. That is, if you ignore his use of performance enhancing drugs. The rules over such drugs weren't as stiff as they are now and Bonds told the grand jury he was unaware of taking performance enhancing drugs.

When Barry Bonds walked into the federal courthouse in San Francisco on Dec. 4, 2003, his career total stood at 658 home runs, baseball had yet to institute drug testing with penalties and the Giants were nearly a half-century removed from their last World Series title.

Much has changed since the brawny, contentious slugger spent 2 hours, 53 minutes answering questions from a pair of assistant U.S. attorneys and grand jurors examining drug use in sports.

Baseball's Steroids Era receded somewhat as players and owners started mandatory testing and then toughened the rules three times. Bonds won his seventh MVP award in 2004 and broke Hank Aaron's career home run record in 2007.

And then on Nov. 15, 2007, exactly 50 days since he took his final big league swing and 100 after topping Aaron, Bonds was indicted on charges he lied to the grand jury when he denied knowingly using performance-enhancing drugs. Even though he wanted to continue playing, all 30 major league teams shunned him. And without Bonds, the Giants last year won their first title since 1954.

Starting Monday, a jury will be selected in the very same court house where Bonds testified all those years ago to determine whether he broke the law with four short answers totaling nine words: "Not that I know of," "No, no," "No," and "Right."

Each of the charges - four counts of making false statements to the grand jury and one count of obstruction - carry a possible sentence of up to 10 years, although federal guidelines make a total of 15 to 21 months more probable if Bonds is convicted.

Prosecutors claim he lied to protect the legacy of a career in which he hit home runs at an unprecedented pace, especially for someone his age. Bonds was 43 when he his 762nd, and last, home run.

His apparent defense?

He was truthful when told the grand jury he didn't know the substances he used were steroids, so even if they were performance-enhancing drugs, that isn't relevant to the charges against Bonds.

"If you look at the cases of athletes internationally over the years, the defenses of those athletes has been, 'I didn't know,"' said Dr. Gary Wadler, former chairman of the committee that determines the banned substances list for the World Anti-Doping Agency. "They clearly know. The question is: In a hearing, can you prove it? But they know. Of course, they know."

Even if that is the case here, prosecutors may trouble convincing jurors.

Much of the government's case has been gutted by the refusal of Greg Anderson to testify. Bonds' personal trainer and childhood friend was sentenced in 2005 to three months in prison and three months home confinement after pleading guilty to steroid distribution and money laundering for his role in the Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative (BALCO) case. He is likely to be jailed again next week because he is refusing to testify at Bonds' trial.

Without Anderson to authenticate key evidence, U.S. District Judge Susan Illston ordered that prosecutors couldn't present three positive drug tests seized from BALCO and so-called doping calendars maintained by the trainer at the trial. Prosecutors tried and failed to get her decision overturned. The appeal delayed the trial by two years, but the government lost in a 2-1 vote by a panel of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Prosecutors allege Bonds lied to the grand jury when he said he didn't take steroids Anderson gave him, never received human growth hormone from Anderson, never took anything Anderson asked him to take before the 2003 season other than vitamins, and never allowed anyone to inject him other than physicians.

Bonds testified to the grand jury he was told by Anderson he was taking "flax seed oil," which the government alleges was a then-undetectable steroid later determined to be Tetrahydrogestrinone (THG), developed by Patrick Arnold for BALCO and known as "the clear." Bonds also testified he used a lotion that Anderson told him was a balm for pain relief, which the government claims was a testosterone-based substance known as "the cream."

With Anderson refusing to testify, prosecutors intend to use the testimony of other athletes, including former AL MVP Jason Giambi, plus the a tape recording of Anderson speaking with then-Bonds assistant Steve Hoskins, to help prove their assertion that Bonds knew what he was taking.

A urine test Bonds took on June 4, 2003, for baseball, which later was found to be positive for THG, also will be introduced along with a July 7, 2006, urine test for baseball that was positive for an amphetamine. And Bonds' former mistress, Kimberly Bell, will be asked to testify about changes to Bonds' body and demeanor the government asserts were caused by steroids.

With the well-established group of BALCO prosecutors led by Matthew A. Parrella and Jeffrey D. Nedrow battling against Bonds' high-priced legal team of half-a-dozen-plus attorneys, the case could come down to how much doubt Bonds' side raises about the government's evidence. The standard for criminal conviction is "beyond a reasonable doubt," not "without any doubt."

Thus far, the highest-profile athlete sent to prison in the BALCO investigation has been track star Marion Jones, sentenced to six months in prison after pleading guilty to lying to federal investigators when she denied using performance-enhancing drugs and to a second count of lying about her association with a check-fraud scheme.

Led by Jeff Novitzky, the tall and imposing lead investigator, the government has been criticized by some for spending millions of dollars on the investigation of Bonds and the separate probe of cyclist Lance Armstrong, who has not been charged. And Novitzky and prosecutors were rebuffed by the 9th Circuit, which ruled they illegally seized the tests results of about 100 baseball players not involved in the BALCO case.

Yet former baseball Commissioner Fay Vincent sees value in the prosecution.

"The legal system has to count on people telling the truth and therefore the government will take seriously charges of lying to federal organizations," he said. "It's important for the federal system."

Illston has urged the sides to try to reach an agreement without a trial, but that recommendation seems to have gone nowhere. And Bonds is only the first Steroids Era baseball star to face a jury. Starting July 6, seven-time Cy Young Award winner Roger Clemens goes on trial in Washington on three counts of making false statements, two counts of perjury and one count of obstruction of Congress.

How Bonds and Clemens are viewed on the 2013 Hall of Fame ballot - and beyond - will be determined by these verdicts. Bonds' season record of 73 home runs and his career mark have been dismissed by some, perhaps many. Now 46, Bonds' statements, accomplishments, physique and reputation will be under scrutiny like never before.

"Obviously some of the romance and mythology of all sports has been diminished," broadcaster Bob Costas said. "That's just a consequence of the modern age. But I think that it's mostly because of the direct linkage to steroids."

Copyright 2011 by STATS LLC and The Associated Press. Any commercial use or distribution without the express written consent of STATS LLC and The Associated Press is strictly prohibited.