'Anjanette Young Ordinance' Aims For Stricter Search Warrant Reforms, Will Be Introduced to Council Wednesday

By Dave Savini, Michele Youngerman, Samah Assad

CHICAGO (CBS) — Members of City Council are pushing for stricter search warrant reforms with a new city ordinance named after Anjanette Young, the innocent social worker wrongly raided by Chicago Police officers.

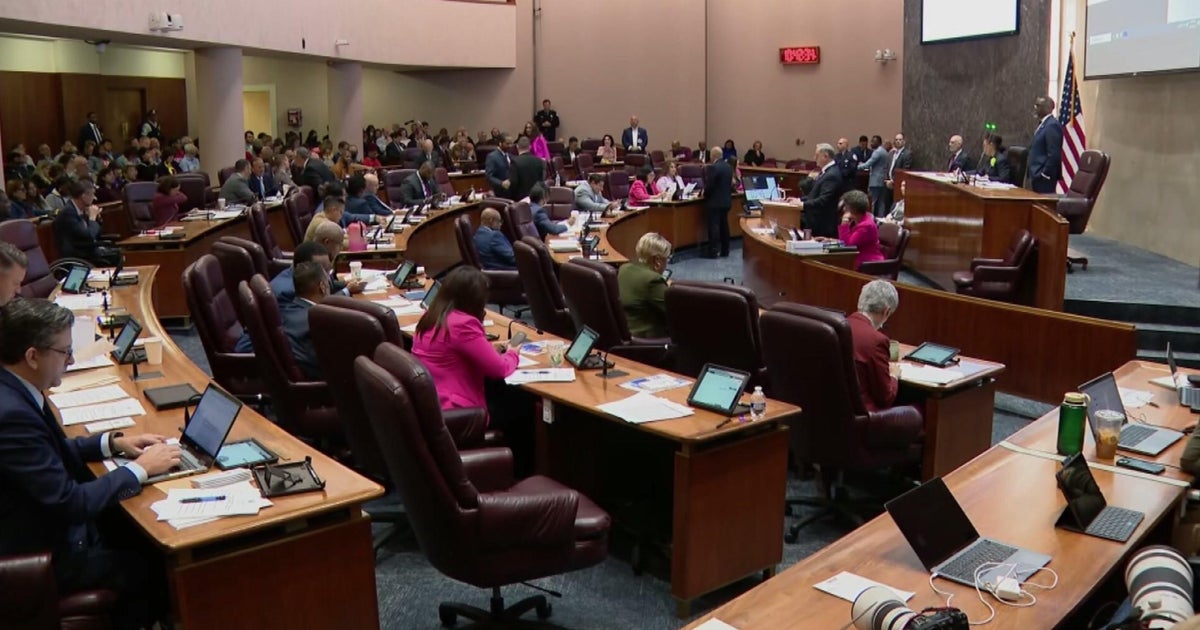

The ordinance will be introduced to council Wednesday morning. If passed, it would become city law. It would also force CPD to add the reforms and accountability measures to its policy. The ordinance is sponsored by five council members: Maria Hadden (49th), Sophia King (4th), Jeanette Taylor (20th), Stephanie Coleman (16th), and Leslie Hairston (5th).

"These wrong raids, time after time, are an example of rules not being followed, protocol not being followed and every day Chicagoans having their civil and human rights violated," said Hadden, the alderwoman representing Rogers Park.

The proposed ordinance comes two months after CBS 2 aired disturbing body camera video that showed the moments police raided Young's home in February 2019.

The video revealed officers handcuffed Young while she was naked and would not initially allow her to get dressed. It also shows how Young stood, naked and handcuffed, telling police they were in the wrong place at least 43 times.

"I would like for no other person to have the same experience that I had," said Young, who filed a lawsuit against the city and police late Friday. She plans to speak at a news conference about the proposed reforms Wednesday morning.

"It is my hope that, with this ordinance, it will make some significant change in the City of Chicago," Young said, "which is what I've been asking for from the very beginning."

Young has become the face of a troubling pattern of wrong raids uncovered as part of a years-long CBS 2 investigation. She is among dozens of people of color CBS 2 found were victims of wrong raids, after officers failed to do basic investigative work to check bad tips from confidential informants.

If passed, the ordinance would require 20 reforms that would overhaul how officers obtain and execute search warrants. Hadden said it's "an attempt to put more teeth" to enforce CPD policies – those of which CBS 2 found officers repeatedly violated but weren't held accountable for.

"It's more than just a policy, it's more than just an executive order even," Hadden said. "It really becomes part of what our laws govern in our city, which gives us…more grounds to demand the type of enforcement and compliance that we want to see."

Among the reforms, according to the proposed ordinance:

- Pre-raid: Officers must knock, announce themselves and give the resident(s) "a reasonable amount of time," or no less than 30 seconds, to respond before breaking the door. In Young's case, body camera video shows officers used a battering ram to break down her door just seconds after knocking. Young was in the middle of changing at the time officers burst in with guns pointed at her. She says she didn't hear the knock, nor would she have had sufficient time to get dressed and answer the door."There was no time for me to consider that I didn't have clothes on, or maybe I should grab something to wrap myself in," Young said. "In that moment, I just put my hands up and prayed that [the officer] wouldn't shoot me."

- Protecting children & vulnerable residents: CPD must "use tactics that are the least intrusive" and reduce physical and emotional harm to those inside the home." This includes limiting the execution of warrants if children are there, and the creation of a special plan if vulnerable people are expected to be at the home at the time the search warrant is executed, including children and people with disabilities. A supervisor must approve this plan."This requires officers to actually develop a plan, beginning and before coming in, and to engage in the execution of a warrant so that it's the least intrusive method possible, the least invasive and most respectful of the rights and dignity to the people inside," said Craig Futterman, Clinical Law Professor with the University of Chicago, who also helped draft the ordinance.CBS 2 has documented how police routinely traumatize children during wrong raids, including pointing guns at, handcuffing or interrogating them, and handcuffing their parents in front of them. Under the Peter Mendez Act, named after a then 9-year-old wrong raid victim interviewed by CBS 2, CPD is currently undergoing training on this issue.

- Timeframe: With the exception of special circumstances, residential search warrants can only be conducted between 9 a.m. and 7 p.m."What we've seen is that Chicago Police have regularly been executing these raids late at night, early in the morning when people and families are asleep," Futterman said. "No one has any time to get to the door to even know that it's police officers who are there. And that's a dangerous situation for everybody."

- Tracking: CPD does maintain some data that tracks the outcome and location of every search warrant. But the ordinance would CPD track and publish additional information, including whether force was used, misconduct allegations and if children were present. The ordinance cited CBS 2's findings, including the majority Black neighborhoods where search warrants were executed the most, while officers rarely served warrants in predominately white communities. Supt. David Brown recently committed to tracking wrong raids like the one on Young in response to an ongoing Inspector General investigation.

- Confidential informants: Officers will not seek a search warrant relying solely on an informant's tip. They must supplement it with an independent investigation and surveillance to corroborate the information. CPD police already requires an independent investigation, but CBS 2 found instances where officers violated those rules without accountability -- including in Young's case. The council members will also propose informants cannot be used if their information has led to a negative warrant in the past.

- Body cameras: All officers will wear and activate their body cameras during the entire raid. Per CPD policy, only two officers on a raid are required. Some officers previously weren't required to wear them, and others violated the policy. The ordinance would mandate CPD retain all video and audio recordings that capture residential search warrants. Currently, CPD policy requires video be retained for one year unless an incident is flagged. In Young's case and many others, video was critical in exposing what happened during wrong raids.

- Supervisory checks & accountability: Officers must seek supervisor review and approval of their independent investigation done prior to seeking a search warrant from a judge. Supervisors must also ensure compliance with the ordinance by regularly reviewing body camera video, search warrant applications and incident reports. If an officer has violated the ordinance, it says, "The Superintendent will immediately strip that member of their police powers and refer the member for further disciplinary proceedings, during which the member may be subject to termination."

You can read the full proposed ordinance here:

Officers are rarely disciplined for raiding the wrong homes, CBS 2 found – except for in Young's case, where the officers involved were placed on desk duty pending an investigation by the Civilian Office of Police Accountability. CPD took those officers off the street nearly two years after the raid, and only after CBS 2 aired the body camera video, which sparked national outcry.

"I think the core points that we're trying to get to, really fall into the category of make sure that the basic civil and human rights of Chicagoans are respected," Hadden said.

Hadden expects the proposed ordinance to receive some pushback, but she is looking to tap into the broad support from council.

"And then, of course, I hope we'll get support from the mayor on this," Hadden added. "I know that she's working on her own reforms. But I think that, what we're proposing, and what we're putting in an ordinance form, is something that everyone should be able to get behind."

Futterman believes the ordinance shouldn't be controversial.

"These are common sense things that are good for families, good for the community, good for the police, good for public safety," he said. "This isn't something that should generate a lot of controversy."

The ordinance is only the latest efforts at forcing chances to CPD's search warrant processes. Futterman is part of the team of lawyers that forced the federal consent decree. Recently, they took the city back to federal court, accusing the city and police of violating the decree with the pattern of wrong raids.

"Each and every one of the provisions in the ordinance goes, specifically to a problem that's been documented and observed right here in Chicago, not just as a one off, but as a part of a pattern and practice," Futterman said. "That's why we need this ordinance, and that's why we don't need just a single one fix, but that's why we need a holistic fix, and something that actually can bring accountability as well."

The proposed reforms also come in the midst of ongoing fallout and criticism directed at city officials, and how Mayor Lori Lightfoot's office handled the case. Just hours before CBS 2's story aired, the city tried to stop CBS 2 from airing the video through a failed attempt in federal court – prompting more backlash and leading to the resignation if the city's top attorney. Later that week, CBS 2 uncovered the city withheld six video clips when they turned over body camera video to Young and her attorney, Keenan Saulter, as part of a federal lawsuit.

Saulter said he believes it was deliberate.

"This is a very clear pattern, and sadly, these are the people that withheld videos from families in the past and media outlets," Saulter said. "They did everything in their power to keep this video from Ms. Young after she filed a [Freedom of Information Act] request.

"The way the city has handled this case, it basically has continued to traumatize her," he said.

After CBS 2 brought Young's story to light, aldermen called and initiated hours-long special hearings demanding search warrant reforms. The Chicago Inspector General also opened an investigation into how the city, including Lightfoot's office, handled the case.

Supt. Brown recently created a new "search warrant committee" and agreed to recommendations. This was in response to a separate, ongoing IG investigation into wrong raids that started in 2019. It's unclear which, if any, changes have been made to the policy.

"Chicagoans' trust in our government and our police department is really at a low, and we've got to get it right if we want to move forward, if we want to have a functional city," Hadden said.

Young said she feels honored that the ordinance is named after her, but what's most important to her is real change.

"When I made the decision to go public…it was about making sure that it was publicly known what happened to me," Young said, "and publicly known that I wanted to fight to make sure this doesn't happen to anyone else."

Multiple community groups helped draft and support the ordinance, including:

- Black Lives Matter Chicago

- Craig Futterman, University of Chicago Clinical Law Professor

- Chicago Westside Branch of the NAACP

- National Pan-Hellenic Council of Chicago

- Network 49

- Progressive Baptist Church

- United Working Families

- Urban Reformers