Winter Weather Forecast: Snowier And Colder Than Average

BOSTON (CBS) - The flakes are starting to fly and the air is cold. Winter isn't coming, it's here! November brings our annual WBZ-TV winter weather forecast as we make an attempt to figure out what the upcoming season will bring. As always, there are some disclaimers which we'll get out of the way right off the bat.

1) Seasonal forecasting is still a budding science. It's generally not going to be a slam dunk or something to take 100-percent literally. It's an educated guess using the science we have available to us and looking at all the known variables involved. We've done a pretty good job in the past several years but there will always be some parts that don't verify.

2) Climatological winter is December, January, and February. When we talk about a warmer or colder than average "winter," it's the average temperature departure over these three months. However, when it comes to seasonal snowfall, we take the entire October-April snowfall into account (and sometimes into May!).

3) Use the outlook as a fun guide for what lies ahead. We start getting requests for our winter outlook as early as September. It's an interesting project to look at everything on the table as we get underway and prognosticate way farther out than our usual 7-day forecast. Every winter is dark, cold, and features snow. This is just an attempt to figure out just how cold and snowy it will be. If you're not into the science, just skip to the bottom :-)

Let's go!

What makes an extra snowy or quiet winter?

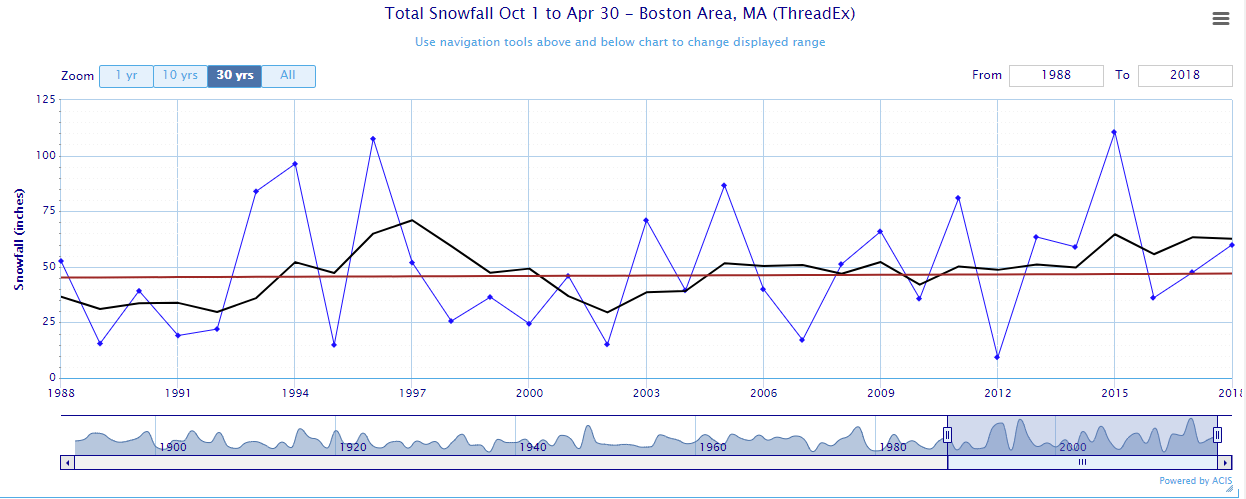

Snowfall over the past 30 years in Boston (at Logan Airport)

Over the past 30 years in Boston, there's been essentially no trend in seasonal snowfall. There have been some very big years and some very quiet years, giving us an average of about 45 inches of snow overall. So why are our winters so variable?

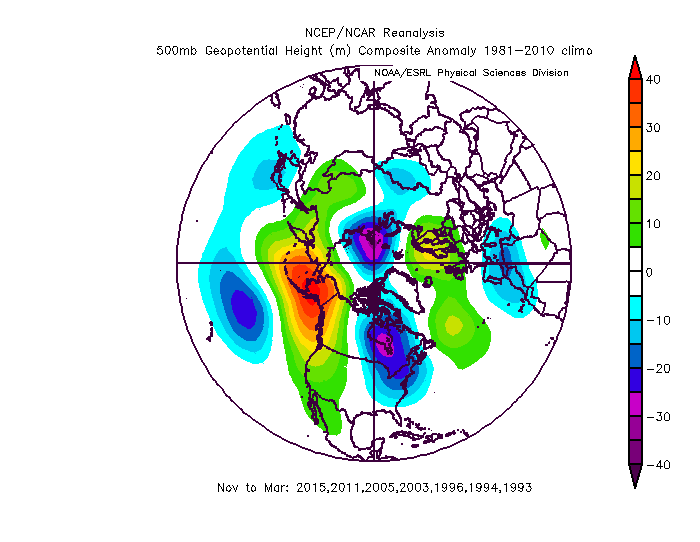

500mb height anomalies during some of our biggest winters for snowfall

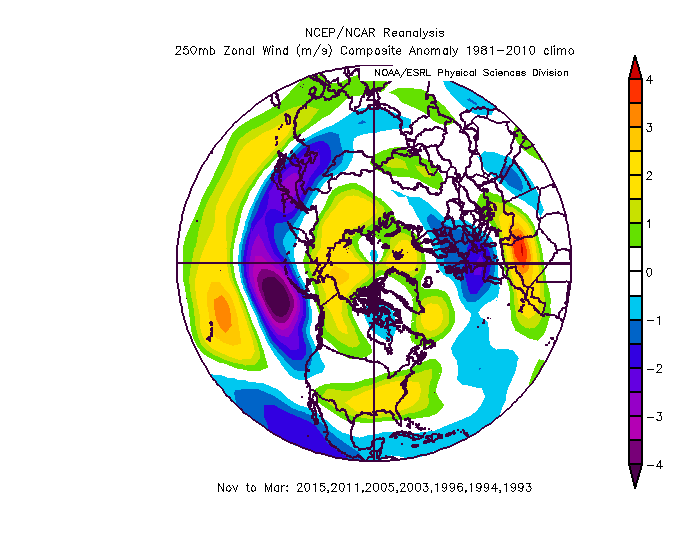

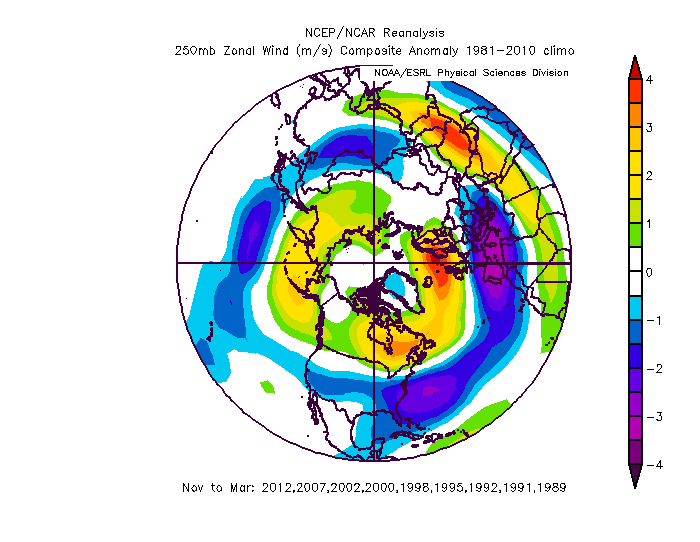

Jet stream level zonal wind anomalies during some of our biggest winters for snowfall

There are a myriad of factors in our atmosphere that dictate how the season will go, but you can see from these charts a generalization of what produces a big year versus a 'dud.' In our major snow seasons (70+ inches) you'll find a more active subtropical jet stream or split-flow which adds extra energy and moisture to the coastal storm equation. You'll also find a lot of ridging across the western U.S. and Canada, which we call a +PNA (Pacific North American pattern). This allows cold air to slide down out of the Arctic into the eastern U.S. and increases our odds of snowfall. A colder winter is almost always a snowier winter.

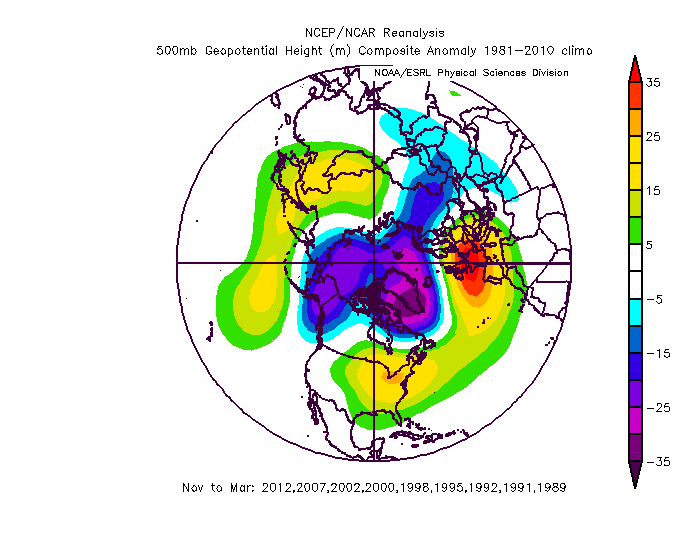

500mb height anomalies during some of our quietest winters for snowfall

Jet stream level zonal wind anomalies during some of our quietest winters for snowfall

The dud winters (less than 30 inches and in most of these cases less than 20 inches) feature a much stronger and less "wavy" jet stream, which stays tighter to the pole and is a sign of a strong polar vortex. This in turn keeps a lot of the coldest air locked up in the high latitudes and allows milder air to dominate the mid-latitudes. Ridging is a common feature in the east and keeps the winter storm track away from us.

We've had as much as 110.6 inches of snow in Boston (the memorable 2014-15 winter) and as little as 9 inches in 1936-37 and 2011-12. Quite a spread!

Does A Wet Fall Mean Anything?

The question we have been getting the most is whether a very wet fall leads to even more moisture in the winter, or if it means we'll run out of gas and not see much snow.

On pace for a record wet autumn in the Boston area. Graphic: WBZ-TV

If you look at the wettest fall seasons on record at Blue Hill Observatory, you'll find that nearly all of the following winters featured near or below average snowfall (this fall may end up the wettest ever recorded, we're already in third place). That being said, I don't think that's going to be indicative of this upcoming winter. Almost all of those following winters featured La Nina conditions or ENSO neutral conditions (and one strong El Nino). None of them have a setup like this coming winter, which is a weaker flavor of El Nino.

El Nino Conditions and Overall Setup of Ocean Temperatures

We've been watching El Nino grow in the Pacific over the past several months, which is a warming of the equatorial Pacific. You may recall that we had a very strong El Nino a couple years ago, in 2015-16. It was crazy warm to start and we barely got any snowfall except late in the game (a February blizzard) that made Boston's seasonal snowfall respectable. What we have this time around is not similar.

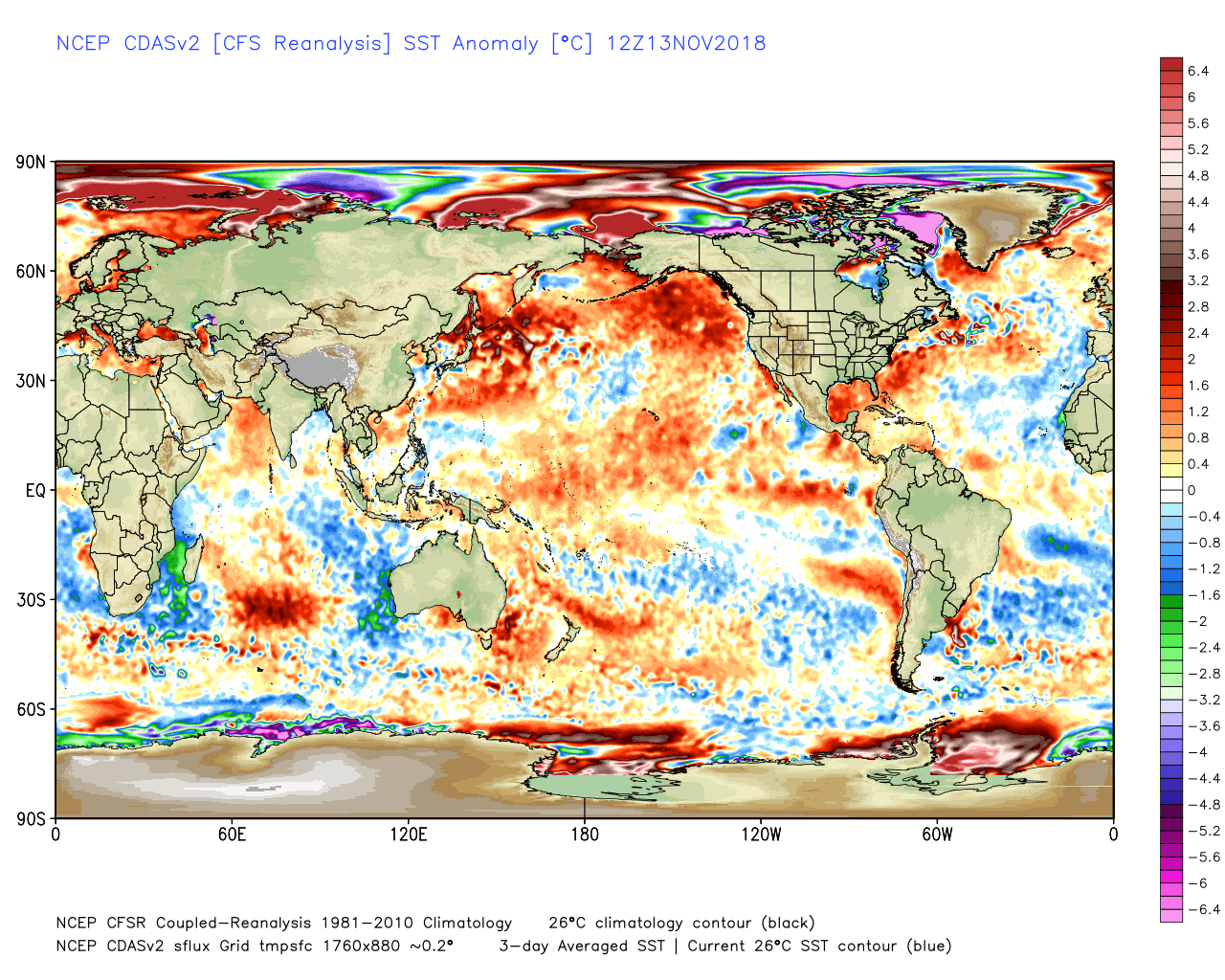

Current SST anomalies as of mid-November

This flavor of El Nino will be a weak to moderate strength central-based El Nino. Instead of having the most unusually warm waters closer to the South American coast, they'll be camped out more toward the central Pacific. On top of that, the north Pacific is on fire. Lots of very warm water south of Alaska and also off of Japan. At the same time, we see cold waters off the west coast of Australia, and lots of anomalously warm water along the eastern seaboard.

The warmer waters matter because they help fuel tropical convection (storms) which in turn release large amounts of heat into the atmosphere. And that heat release helps to shape the jet stream. This sort of setup tends to favor a lot of ridging across Alaska and the western U.S./Canada, which in turn sends a trough down across the eastern U.S. Plus, the warm waters off the East Coast can add some extra fuel to developing nor'easters when cold air masses clash against the mild ocean.

El Nino winters tend to hit their stride later than La Nina winters (you may recall last year we called for a lot of early cold and snow potential at the start of winter, and indeed the coldest air of the whole season was December into early January). That being said, this year may buck that trend. There are a lot of indications that the western ridge/eastern trough setup will get going early in the season and produce more snow and cold chances in December than a more traditional El Nino year would.

The Polar Vortex

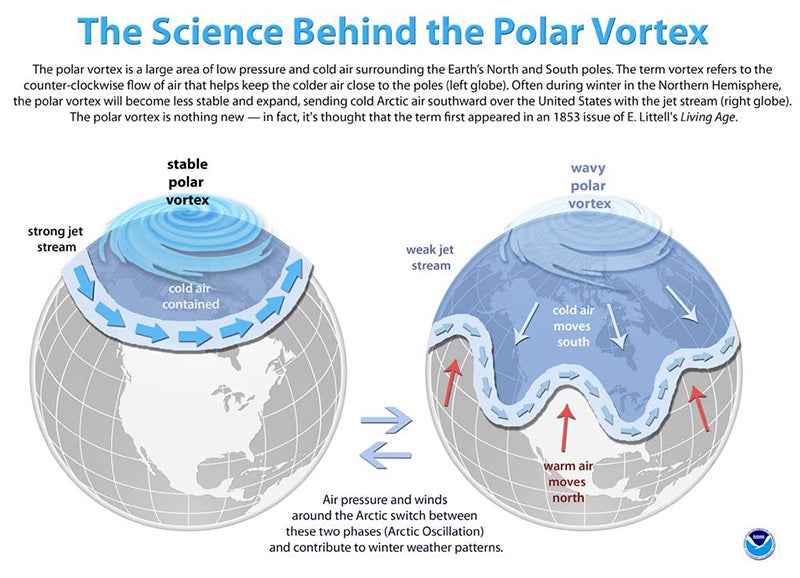

Oddly enough, this term that generally hid in atmospheric science classrooms and textbooks burst into pop-culture in 2013 and has been a headline favorite every sense. What is it? The polar vortex is a circulation very high up in the atmosphere (well above the jet stream) that strengthens in the winter and weakens during the summer. When it's strong, cold air hugs tighter to the pole and doesn't escape frequently. When it's 'perturbed' or in a weakened state, it can wobble and stretch and help send frigid air farther south and 'empty the freezer door.'

Source: NOAA

It's taking a few lumps so far this November with some more minor disruption expected later in the month. I wouldn't say it's on the ropes but it's seeing enough disruption to keep early cold risks higher than a typical El Nino December. The million dollar question is whether it will stop taking these hits later on in December and allow for a reprieve in January. In my opinion, the strength of the polar vortex is a major player in our temperatures and can trump many other atmospheric factors. We'll have to see how it develops in December for later-season impacts.

The Solar Minimum

Tied in to the polar vortex is the fact that we are at the minimum of solar cycle 24. The solar cycle is a roughly 11-year cycle of sunspot activity. Recent research has made some ties to where we are in the cycle and the strength of the polar vortex. In general, it is believed that high sunspot activity and help produce a stronger polar vortex while low sunspot activity can produce a weaker one. Being at a minimum now, odds may favor more disruption to the PV this winter and a colder outlook. For what it's worth (coincidence or not) the stretch from 2008 to 2011 featured some very snow winters from the Mid-Atlantic to New England.

Source: https://www.swpc.noaa.gov/products/solar-cycle-progression

The AMO

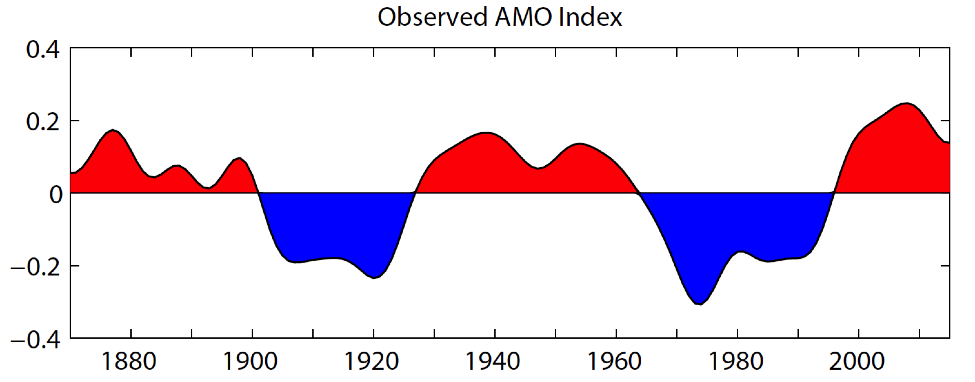

How about some more acronyms! The AMO is the Atlantic Multi-Decadal Oscillation. As the name suggests. it's a pattern that tends to switch up after more than two decades. This is an oscillation that tracks sea-surface temperatures in the North Atlantic. It just so happens that our seasonal snowfall does a nice job of tracking along with the AMO. The warm (positive) phase includes many of our snowier stretches in the Boston area, while the cold (negative) phase captures a lot of our quieter seasons. We're likely on the downswing, but still in +AMO territory and can probably squeeze out a few more years of these busy snow times before a possible flip. Next decade, perhaps?

Eurasian Snow Cover

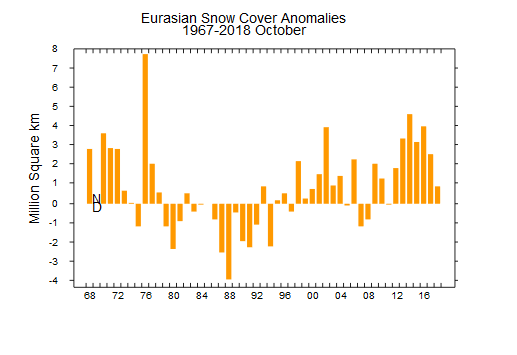

There have been studies by Judah Cohen that suggest a link between the advance of autumn snow cover across Eurasia and winter snow/temperatures. A faster and more expansive October snow advance can in turn produce a stronger Siberian high pressure in winter, which has a downstream effect of disrupting the polar vortex and bringing colder temperatures to the eastern U.S. This autumn, we saw a fairly middle of the pack snow advance (although across the entirety of the northern hemisphere early snow cover is extensive. I don't really see this year showing its hand as strongly as some of the past few.

Conclusions! What's Expected This Winter?

If you made it through all that, congratulations! You are a curious person and I love that about you. If not, I understand. You don't want the labor pains, just the baby. That's fine too.

Here's how we see the winter unfolding. We know it's already snowing out there, and it looks like there are some early-season snow risks on the table late November through December. Ski season will be off to a ripping good start and it won't be difficult getting into the holiday spirit. December likely ends up colder than average.

If a month 'relaxes' some and offers a chance for warmer than average temperatures, my money would be on January.

Most of our weak El Nino winters and most of the seasonal computer guidance all point to a rocking February into March as 'prime time' for the winter. In my mind, the biggest question mark during this period is whether there will be very aggressive North Atlantic blocking. It looks snowy in the eastern U.S. but if the blocking is extra strong it may help shunt the snow track farther to our south a la 2009-2010. Either way, it looks cold with solid snow chances on the table.

For snowfall, we are calling for 55-to-65 inches of snow at Logan Airport in Boston, with higher amounts away from the coast. It should be an above average season for snowfall and perhaps by a wide margin. This is pretty remarkable, because if it verifies it would make 6 of the past 7 winters snowier than average in Boston! This is while temperatures are warming long-term, so it's quite an interesting development. Four of the five warmest winters on record in Boston are since 2001 with 3 of them this decade alone. We haven't had a Top 20 coldest winter on record in the last 60 years.

Which brings us to temperature. Overall, we expect a colder than average winter this time around. I think this will be most noticeable in February, particularly compared to the past couple years that have been complete blowtorches!