What's being done to fight recent 'swatting' calls that prompt school lockdowns?

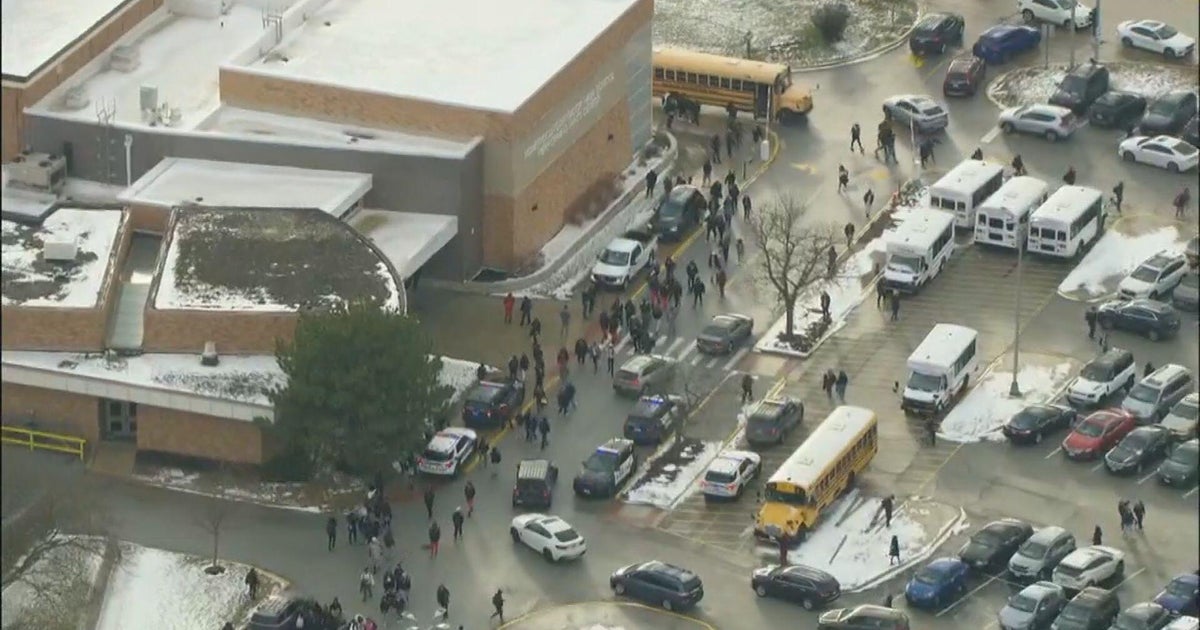

SALEM - Cars of parents were already lined up for half-day dismissal in Salem Wednesday when the school went into lockdown for a so-called active shooter. But there was never an active shooter near the school.

"We kind of suspected that Salem would come up with one of these hoaxes of a school shooter," Police Chief Lucas Miller told WBZ.

Because of that, his department was prepared with a somewhat tempered response.

More than a dozen Greater Boston schools went on lockdown this week, prompted by the same - or very similar - recorded 911 hoax calls. "Somebody says 'hey I am outside of school and I'm on my way in to shoot it up,'" Miller explained. But the entire threat is fake, designed to prompt a massive police response and waste resources.

Incidents of "swatting" have been spreading across the country recently. Last week, there was a rash of incidents in Vermont, and this week, in Massachusetts.

The FBI estimated thousands of swatting calls prompt a police response each year, and the federal agency is helping local districts investigate the recent calls.

While the threat might not be real, the police response and school lockdown is. "We respond as we would if it was the real thing," explained Lieutenant Brian Goldman of Concord Police, which responded to a swatting call at Middlesex School this week. "We don't have a choice. We can't guess and say, 'oh it's a hoax' and then not go there and then something happens."

The lockdowns can cause high anxiety for students hiding under their desks and for parents begging for information. "Obviously we were kind of worried and we didn't know what was happening, but we just closed the doors," Salem High School senior Aaron Dwyer explained to WBZ after he was in class for the brief lockdown. "I saw a bunch of cruisers come spinning up, and I, being that mom, kind of freaked out a little bit and started texting," his mother Deb said.

Dr. Erica Lee is a psychologist at Boston Children's Hospital who often speaks with families about the fear sparked by these lockdowns. "I think the uncertainty of not knowing for sure if our kids are going to be safe is something that both parents and kids really struggle with, it's really the primary thing that we are often seeing as psychologists is kids and parents saying just 'I worry a lot about my child,'" she said. "When these swatting incidents are happening, 'I don't even know if I should send my child to school.'"

The best thing parents can do, Dr. Lee explained, is to be honest with their kids at an age-appropriate level. "Even though these lockdown drills can be so stressful because they're just really odd, the idea that a bad person can come into the school, there might be an emergency, we may need to hide, and that thing can be really scary for kids... The more they have practiced it, the more they understand what the safety protocols are...This actually provides predictability and a sense of calm if and when they have to do a drill or when something goes wrong."

While "swatting" has serious consequences, legal experts tell WBZ more can be done to fight it at the source. "What's interesting is that very few states actually have laws on the books to address anti-swatting, or to penalize it," WBZ Legal Analyst Jennifer Roman said.

Massachusetts does have a law on the books for state crimes, but it makes swatting only a misdemeanor punishable by up to one year in jail.

However, many swatting cases originate outside state lines. "The call is placed in Ohio, [for example]," Roman said. "But it's being received in Massachusetts. We've now implicated interstate jurisdiction so the federal government can get involved, the FBI can get involved."

At that point, swatting is punishable by up to five years in prison, then up to 20 years if the call results in bodily injury, then up to life if the call results in a death.

For example, a man is facing 20 years in prison after a fake 911 call in Wichita, Kansas in 2018 resulting in officers killing a man inside his home due to false information. The swatter "didn't pull the trigger," Roman explained. "A police officer did, but it was in response to one of the swatting incidents and the police responded with appropriate reaction."

Due to the presumed hundreds of thousands of dollars in manpower and time that swatting incidents can cost towns, Roman believes the laws need to be stricter and more specific both at the state and federal level.