Hurricane Joaquin: Encouraging Trend, But Staying Wary

BOSTON (CBS) - If you ever wonder what's involved in being a meteorologist, I'd give you a list of things like math, physics, love of science, some weird work hours, an understanding spouse, etc. But the most important part of the job? Communicating.

View: Hurricane Tracking Maps

The toughest requirement is to take something that's really complex (the weather), stare at a ton of data that looks like gibberish to the average non-weather geek, and then let everyone know if the weekend will be great, if wind will take down trees, or if you need to take their boats out of the water before they're destroyed.

Perhaps it sounds simple enough, but coming up with the right words and images for a significant weather situation is quite a challenge.

OLD cone that was issued Thursday afternoon. Looks like New England is in the direct crosshairs, when it was really just an intermediate adjustment toward what was more likely - out to the east. Source: NHC. Get the latest track forecast HERE.

One of those challenges is the 'cone of uncertainty' that is ubiquitous during tropical season. These are issued by the National Hurricane Center, and updated (typically) every 6 hours.

But for a simple product like the possible path of a storm, a ton of confusion arises. Case in point was Thursday. The NHC came out with a cone that seemed to show the center of Joaquin passing just a few miles off of Nantucket. Was this the most likely path? No. Not even close.

For the entirety of this week, the strongest possibilities have been a left hook into the Mid-Atlantic, or out to sea. So why do we get a cone in the middle? Could be for one of two reasons. One is that the NHC doesn't like to make drastic changes with each advisory. Historically, they make incremental changes over time. Even if everyone in that office thought the storm was going out to sea, they don't move the cone out to sea. They go halfway and then wait to see if the trend continues, then keep moving it. The discussion that went along with that cone even said that it was well west of nearly all the guidance, and that they expected to move it farther out to sea.

But what do you see? That big red line down the middle of course! There's nothing I would expect anyone to infer from that arguably the most well known hurricane graphic except that the most likely path was right at us. Hopefully we can come up with a way in the future to avoid situations like this, and figure out a better product to illustrate a storm's future path. In any case, things have not changed much since Thursday. And that may be good news for us in the long run.

For starters, check out this graphic put together by a fellow weather colleague, Greg Fishel. Consistency is a beautiful thing when it comes to modeling (Numerical Weather Prediction). Usually consistent results from run to run display a higher level of confidence in the outcome. Look at the ECMWF. For days all alone with an out to sea solution, it has stuck to its guns. It's your friend that you call whenever you're in trouble. The one you can count on to have a steady hand. The GFS is your crazy beer-crushing roommate from college. One day it's in North Carolina. The next a couple hundred miles east. Then in Virginia. Then hundreds of miles away out to sea. It is starting to appear once again that the ECMWF is king, and the most reliable model for these tropical events.

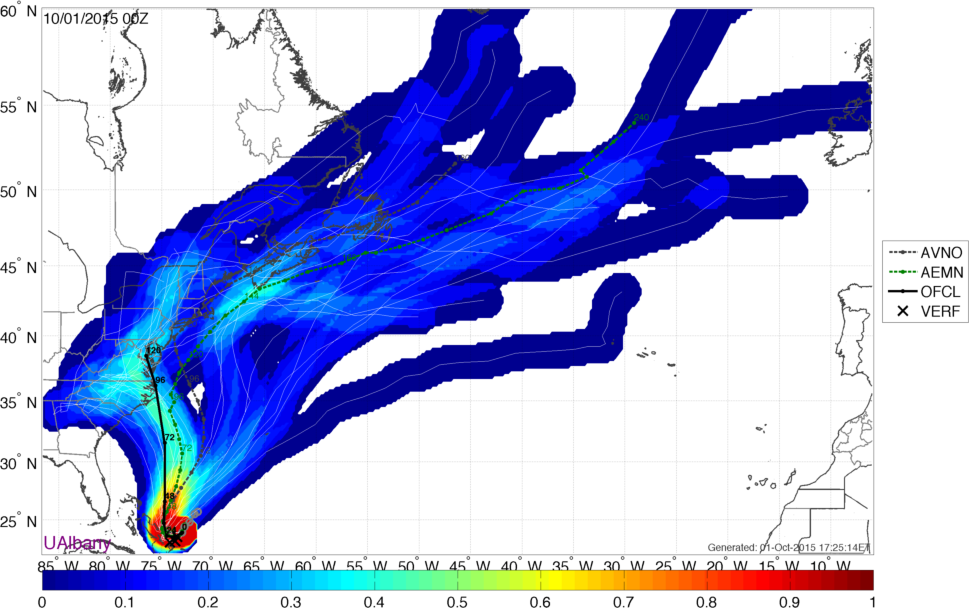

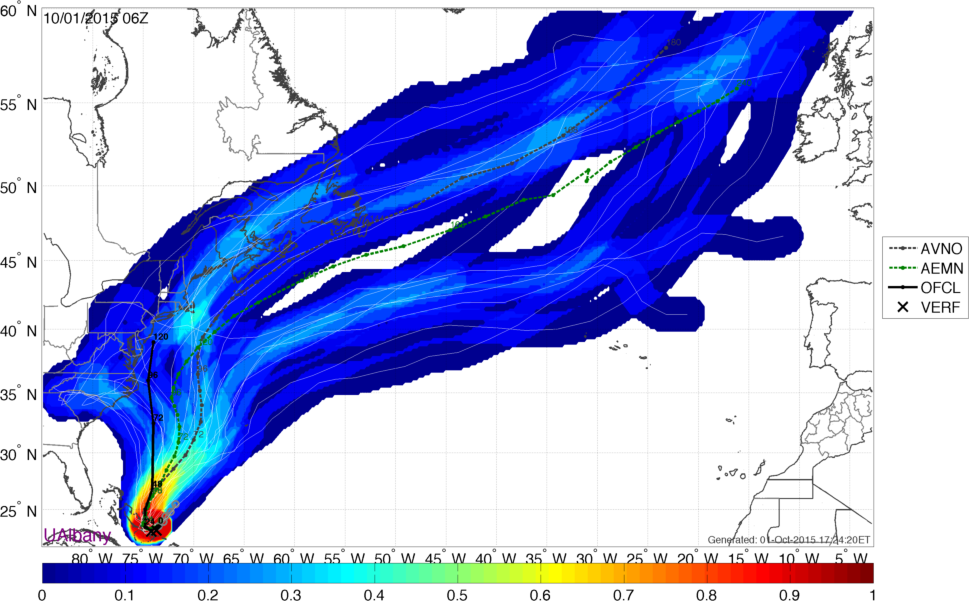

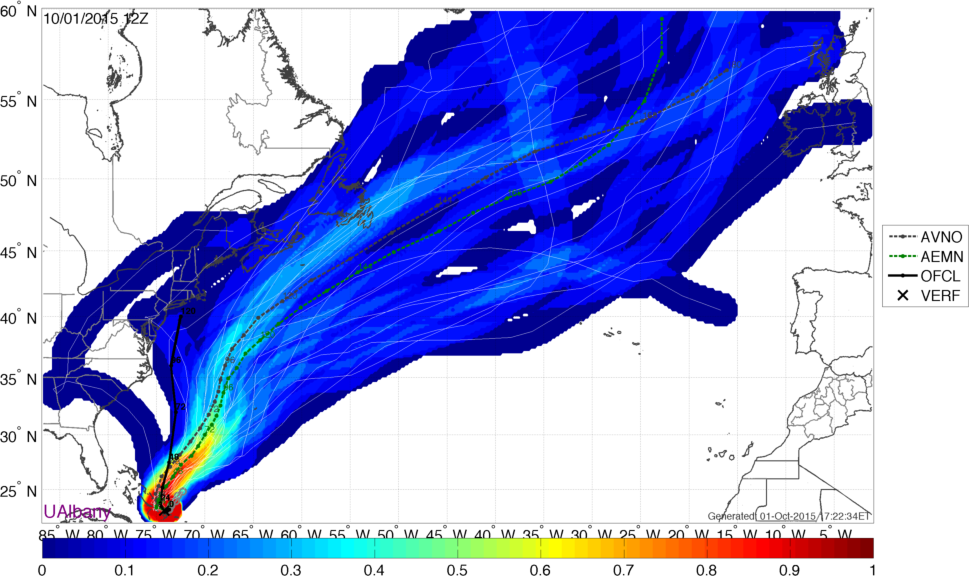

GEFS Ensemble projections from the previous 3 runs of the model. A clear trend emerges. Source: SUNY Albany Earth & Atmospheric Sciences

All other models have been trending toward the European. Above is a sequence of GEFS solutions (the American model's ensemble system). Several straight runs trending farther east each time.

The flagship U.S. hurricane model, the HWRF, has also now broken its previous insistence on a North Carolina landfall and has been out to sea for a couple straight runs. The GFDL is trending east, although not all the way out to sea yet. What is the cause of this trend? It may be all the additional data that started going into the models on Wednesday evening. NOAA has been sending Gulfstream aircraft into the environment all around the storm, taking measurements in the atmosphere that surrounds Joaquin. There are also dropsondes from hurricane hunters, and extra weather balloon launches taking place from NWS offices on the mainland. They make an extra effort to sample as much of the atmosphere as possible, because a more accurate depiction of the environment going into the models leads to a better solution in the end. Conversely, 'garbage in, garbage out' is a phrase we use for poor data to initialize these models with.

18z HWRF model on Thursday - heading much farther east than previously indicated. However, the projected future of Joaquin is still close enough to New England to keep a close watch on its progress. Source: Weatherbell

But why has the ECMWF had such a good track record? Studies suggest that the model has superior internal physics, especially when it comes to the parametrization of cumulus clouds. It may sound silly to think that a whole model could be better because it recognizes and resolves some puffy white clouds better than other models, but it seems to be making a difference. No matter how the U.S. tries to improve it's models, the Euro is still king (though not infallible).

Now just because all of these models are trending east does not mean we are out of the woods.

We're still dealing with a dangerous storm that is extremely powerful. In fact, it's the strongest storm in the Atlantic since Igor in 2010 (bottomed out at 924mb) and the strongest hurricane to move through the Bahamas this late in a season in 149 years! And the astute observer will note that both A) there are some members of these models that curve back inland and B) even some of the out to sea models are very close to southeastern New England.

There is no reason to count out a solution that could bring a serious impact here.

We're talking about Joaquin's future 4+ days down the road, and as we've already seen it has been an unusually difficult one to forecast.

So what to do?

Stay vigilant and up to date over the next couple of days.

There's no need to take immediate action yet, but it may be a good idea to think about your hurricane preparedness just in case. Some towns have already started staging crews/supplies to be safe.

It is looking likely that the storm will miss us, but even a close pass could bring coastal flooding, erosion, and other issues. There's plenty of rough seas in the forecast even without Joaquin through the weekend with constant onshore winds. Plus, Joaquin's wind field should expand as it moves north and starts to interact with jet stream dynamics.

The trend is our friend, but it's never wise to sleep on nature. As always, we'll keep you updated!