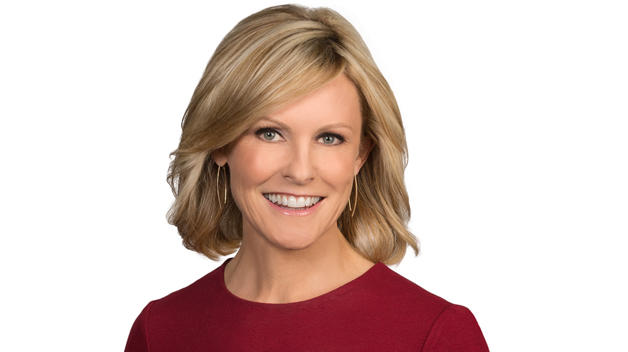

Dana-Farber doctor designs program to address disparities in cancer care

BOSTON - Dr. Christopher Lathan is focused on removing barriers that prevent some of Boston's most vulnerable residents from getting the health care they need. "Working poor folks of all races, but disproportionately Black and Brown communities, have not been able to get the same benefit of the incredible care that we have around us even though they're right here in the city," Lathan said.

As an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (specifically a lung cancer doctor) he wanted to address disparities that he saw firsthand. His father died in his early fifties from congestive heart failure. His mother was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer's Disease in her early sixties. That's when he says he understood-for the first time-what unequal treatment looked like. He started giving his mother his business card. When she handed the card to emergency room doctors, they treated her differently. She was no longer an older Black woman. She was the mother of a doctor.

Dr. Lathan intervened directly when his younger brother had a brain aneurysm at 25. After complaining of a severe headache, he was sent home from the emergency room without a single test or scan. "They thought he might be on drugs or something like that," Lathan recalls.

His brother wasn't on drugs. He was in danger of dying. Dr. Lathan returned him back to the emergency room (at this point his brother was also disoriented) and challenged the staff. "If this gentleman was an investment banker, you would have already scanned his brain. They did. And he had a bleed. He lapsed into a coma about a half-hour later. The surgeon told us if we hadn't done that, he wouldn't have made it," Lathan said.

In 2009, a mentor posed a question to Lathan that sparked the creation Dana-Farber's Cancer Care Equity Program. "How can you fix this gap between people we see in our working poor communities and getting them into our cancer centers? If you could do it in a paragraph, what would you do?" Dr. Lathan started looking at existing models for an idea.

Cancer centers, he realized, had outreach plans for breast cancer or prostate cancer. But there was no access plan; no program linking centers where patients see their primary care doctors with cancer care. Other specialties, including cardiology, use a model that involves a "nurse navigator" who helps patients get the cardiac care they need once they receive a diagnosis. The collaboration between the primary care doctor, the nurse navigator and-ultimately---the specialist gives the patient a more convenient way to get answers from doctors they trust.

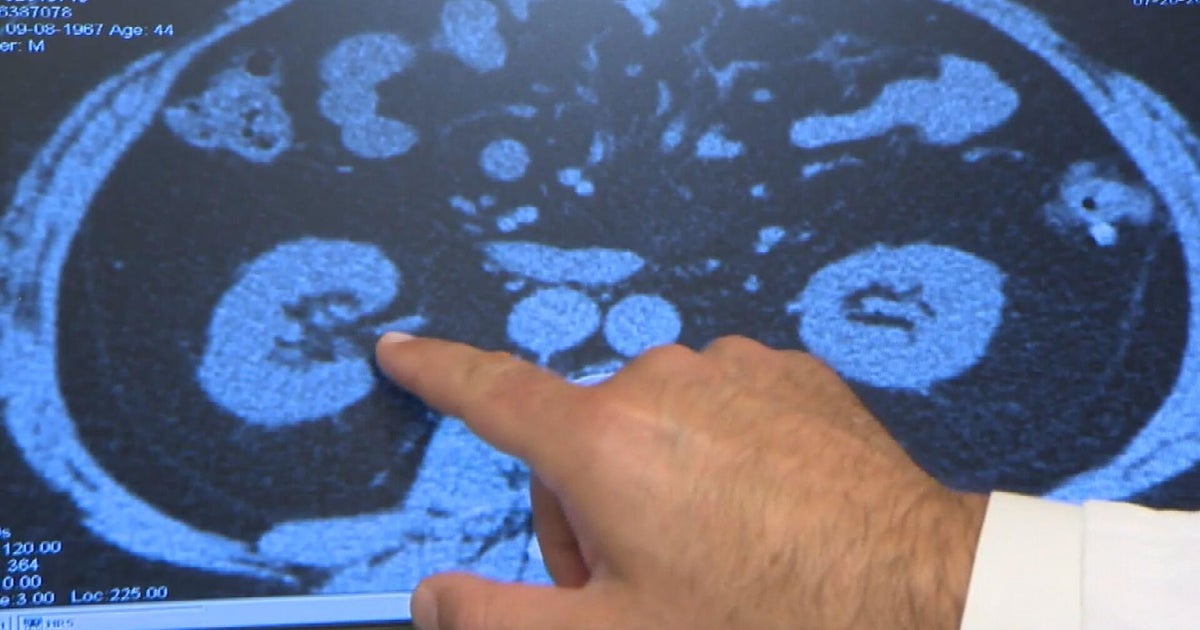

Dr. Lathan saw the promise in a plan that, if successful, could make it possible to diagnose patients with cancer sooner. Getting the diagnosis is the key to getting treatment. Diagnosing people later affects survival rates. Dr. Lathan was motivated to use the model, with a nurse navigator, in Federally Qualified Health Centers. Lathan says, "That's where people are doing great work-heroic work really-taking care of their communities."

With help from Dana-Farber colleagues, he wrote and presented his first business plan. Decision-makers praised it but told him that there was no money for the program. Lathan was crushed but not defeated. In 2012, A $3-million-dollar gift from the Kraft Family Foundation launched the program. "Without that gift," Dr. Lathan says with gratitude, "it never would have happened."

Almost 12 years later, the program operates at Dimmock Community Health Center and Harvard Street Community Health Center. Members of the Dana-Farber team work in those centers twice a month. Doctors who observe abnormalities in a test, scan or blood work have direct access to the oncology team. Patients can get answers from the specialists at the same place where they receive primary care. By giving them information, guidance and options in their community health center, the program aims to reduce patient stress.

For patients in underserved communities, taking time off for appointments and treatment can be a particular hardship. Lathan remembers vividly that his father, a machinist for Milton Bradley in Springfield, never took a day off-not because he was always well but because he couldn't afford to miss a workday. Offering the opportunity to talk with specialists in one setting can alleviate some of that burden for patients who need to maximize time away from work.

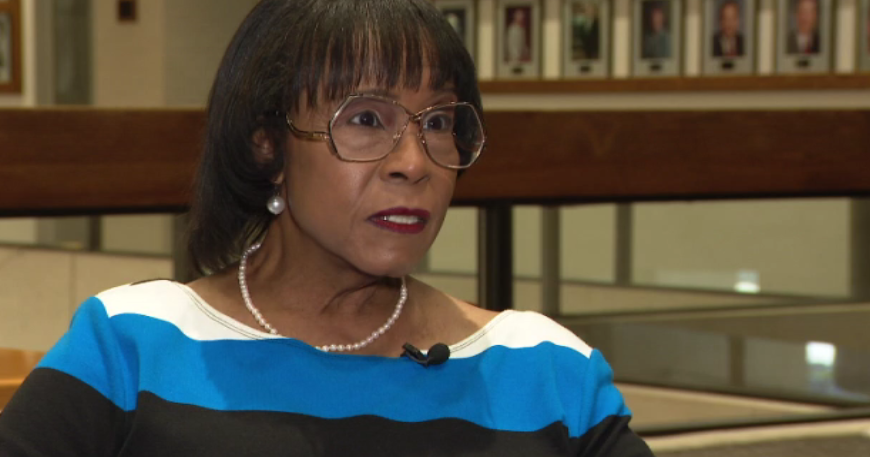

When patients need treatment at a cancer center like Dana-Farber, the nurse navigator is there to facilitate that "next step." Oncology nurse Ludmila Svoboda (who's also the program's nurse navigator) thrives in this role. The day we visited, she was spending time with patient Carol Walker. "We will treat you as if you are a family member," Ludmila explained. "We see patients side by side with their primary care physician. There's a lot of collaboration."

Carol, who is legally blind, has been a patient at Harvard Street for 50 years. When her white blood cell counts spiked about a year ago, Ludmila suspected leukemia. She was right. Ludmila helped Carol make appointments at Dana Farber to determine her treatment. Initially, Carol was skeptical that the oncologists would listen to her concerns. "I would expect doctors to know it all. 'Do what I say!' But they weren't like that," Carol said.

Carol, who swears by a healthy fruit juice full of nutrients, agreed to begin oral chemotherapy. She says she feels good, her white blood cell count is normal, and she has formed tight bonds with her care team. "I feel so special. I feel so good because these people-they actually care," she said.

That trust is precisely what Lathan and his team hoped to create when they designed the program. Harvard Street's President and CEO Charles Murphy says it has been tremendously helpful to primary care doctors who see hundreds of patients every week. He adds that the partnership is a point of pride for Harvard Street. "It's an opportunity for our patients to benefit from world class care," he said.

Ludmila points to their work in the FQHC's as the place where health care and social justice meet. When it began, data showed that people of color-even those diagnosed with cancer-were dying at higher rates. Looking at what happened between abnormal symptoms to diagnosis and care, "There were huge gaps. Some people lingered in primary care. Or they went to the emergency room and bounced around."

Playing a role, as a partner in the program to close those gaps fills her days with meaning. "The biggest difference is that we are here...We see patients in their home," Ludmilla said. She praises Dr. Lathan for his dedication to addressing disparities long before it was on the nation's radar. "It was his idea when nobody wanted to listen," she said.

She says, for the first ten years, they operated in the health centers without attracting much attention. "We were-every week-in the community doing exactly this. But people didn't have the focus on equity, disparities and so forth," she said. Dr. Lathan, whom she now considers family, never wavered in his commitment. "Through his own lived experience, he was light years ahead," Ludmila said.

People are definitely paying attention now. Lathan was invited to the White House in 2022 as part of President Biden's "cancer moonshot" forum. This year, he published a paper in the Journal of Clinical Oncology Practice in which he outlined the program and cited specific successes. At the two FQHC's, the time to a cancer diagnosis has dropped from 32 days to 12. In addition, more underserved patients have taken part in clinical trials. That's been an unintended benefit but one that could prove especially valuable for current and future patients. "In oncology, more than any other field," Lathan explains, "we're changing our drugs year to year."

Participating in clinical trials provides patients access to the latest drugs and gives doctors critical information about the relationship between the genetic signature of a cancer and targeted therapies. An accurate representation of a treatment's success depends on recruiting patients of all races.

Dr. Lathan is proud of the program that he and his team have built and hope to expand. "It's a palpable way to do great things," Lathan said. It is a clinical program he believes in and one (but not the only) approach to fixing disparities in health care. "What we hope to show is that it's not just helpful. It's not just the right thing to do. But it's actually going to have a measurable difference," Lathan said.