Climate change is making winter weather warmer and "weirder"

David Schechter is the host of "On the Dot," a journey to understand how we're changing the Earth and the Earth is changing us. In this essay he shares his experiences while exploring how winter has become our fastest warming season. Watch his previous story about the invisible problem of carbon dioxide here.

It's been a weird winter.

Record snow in Buffalo. Ice in Texas. A parade of atmospheric river storms in California. In parts of the Northeast and New England, January was one of the warmest months ever, followed by an historic cold snap in February.

That news is one thing on my mind as I begin a journey to understand what role climate change is playing in unreliable winter weather. The other thing is how Americans of all political stripes work hard to live inside a perfectly controlled bubble of year-round, 72-degree air.

Extremes are not our thing.

I live in Texas. Here, in the summer, staying comfortable means moving swiftly through the air-conditioned train cars of life, from home, to car, to office, to gym, to dinner.

Brutal winters? Growing up, I endured a few dozen of those, too. On more than one occasion, I was guilty of sprinting to my car, hurling f-bombs at the top of my lungs into the whipping wind.

I totally get the desire to seek personal comfort. But as I prepare to do something that will make me very uncomfortable — take a dip in frozen Minnesota lake — I've been thinking a lot about what we miss when we avoid the extremes, particularly when our planet's well-worn seasonal patterns are changing before our eyes.

Winter is getting warmer

A great example of the weird winter the nation's experiencing is in the Twin Cities. It's been a season of heavy snowfall, but the air was warm enough that some lakes took much longer to freeze, forcing organizers to delay a much-anticipated Luminary Loppet night-time parade on a Lake of the Isles.

Scientists are reluctant to blame any single weather event on climate change but Heidi Roop, Ph.D, a climatologist at the University of Minnesota, says the larger patterns are what she looks at and all of them tell us winter weather is getting warmer and less reliable in the era of climate change.

"What we are experiencing, as whole, in aggregate, is what we expect from climate change," she says. "That volatility, that unpredictability, that weirdness, if you will, is climate change," adds Roop.

And these changes can be measured.

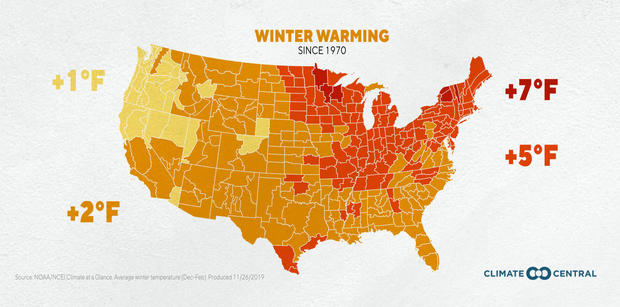

An analysis by the group Climate Central shows that since 1970:

- Winter around the Pacific Northwest has warmed by 1 degree Fahrenheit.

- From Southern California through the middle of the country, winter has warmed by 2 degrees.

- Parts of the Midwest and East Coast have warmed by up to 5 degrees.

- Certain areas of New York, Vermont, and Northern Minnesota have experienced extreme warming of about 7 degrees.

"That change in winter is deeply meaningful and deeply personal and touches us all in a different way," says Roop.

She's game to join me for that cold water dip in Minneapolis' Lake Harriet.

At a hole in the ice called the Harriet Magic Hole, we're the guests of a group of hardy regulars who do this every winter morning.

Tara Young is one of them. When we show up at 6:30am, Young already had a saw in hand, ready to cut away the ice that froze over the hole from the night before.

"Before I started doing this, winter was kind of a nuisance and something that I didn't enjoy. Something that I just suffered through," she says. "This practice has totally changed my relationship with winter," Young adds.

Buoyed by her enthusiasm, Roop and I followed her instructions and quickly got into the lake. Chest deep in near-freezing water. My brain goes blank. I'm breathing heavily. Trying to absorb the shock to my system.

My body goes numb in the cold water and a sense of calm settles in. I'm surprised how fast the shock wears off. My field of view opens back up. I feel blood pooling up around my heart, filling me with energy and a sense of well-being. All the while, the regulars laugh, chit-chat and shower Roop and me with encouragement.

And guess what? We stayed in the icy water for 5 minutes. Five minutes!

"Winter is hard in Minnesota. It's dark and it's cold and it's really long. This gives us a place to kind of come together and have a good time and embrace this," Young says.

For a guy who never liked winter, I liked this.

A lot.

But what happens to northern traditions like this as winters get warmer? That's what I want to know from Roop.

"Will there be seasons? Yes. We don't determine that. Will there still be winters? Will it still be cold? Will it be warm? Will it be weird? Yes. But will it likely be weirder? Definitely," Roop says.

In response to the threats that Minnesota faces from climate change, the state legislature passed a new law that addresses a root cause of climate change, carbon dioxide emissions. By 2040, the state will require all electricity to come from renewable sources.

And the Twin Cities community is also organizing in other ways to protect winter, stepping up its embrace of cold weather events, rallying around a huge pond hockey tournament in January and a major cross-country ski race in February.

Off the snow and ice, folks in Minneapolis-St. Paul are striking up public conversations about how to fight and adapt to climate change. In particular, The Great Northern Festival offers a long list of performances, public art projects and public lectures with a focus on protecting northern culture and cold winters.

But can one state, one community, one festival make a dent in the global problem of climate change? That's what I asked Jothsna Harris, a board member for The Great Northern.

"Climate change is global, but how it shows up is local," Harris says. "Our progress on climate solutions has been really driven by the local level, the city and state level. And what happens at that level has the potential to bubble up."

Let it snow. Then let it stick.

OK, let's head from Minnesota to the Lake Tahoe area of California's Central Sierra Mountains.

It's been a snowy winter up here and it's gorgeous, with the towering pine trees coated in a sticky white frosting of snow.

Meanwhile, down on the road, our little rental car is spinning its wheels like a puppy on a hardwood floor. The highway warning sign says our tires must have chains on them.

That's how I find myself at Mountain Hardware in Truckee praying they have chains in stock. Not to worry: At this snowy oasis of winter supplies they have everything — in multiples. I buy a set of chains. The clerk even teaches me how to put them on. But he leaves the dirty work to me.

Pretty soon, we're back on the road to visit Andrew Schwartz, Ph.D. He's an atmospheric scientist with the University California, Berkeley. He runs the Central Sierra Snow Lab at Donner Pass.

Today, I'm helping him dig a 7-foot hole in the snow, deep enough inside for both of us to stand up. It's called a snow pit. Just like a geologist looks at the layers of rock in a cliff, a snow scientist can gain understanding from looking at the layers of snow.

"It has the different layers from different storms. We can see a little bit of ice there," Schwartz says, pointing to the different layers in the snow pit.

"So, we get measurements of the temperature of the snowpack to figure out, you know, is it ripe for melt? Is it still pretty cold?" he says.

Melting snow is obviously bad for winter sports tourism, a $12 billion industry, but the concerns about the future of snow are even larger than that.

So, let's talk about snowpack. That's water, stored as snow in the mountains.

Traditionally, snowpack melts in spring and summer and that's where 30% of California's water comes from. If it melts too early, it can cause floods in the spring, and by summer there may not be enough water when it's so critical.

These layers of the snowpack Schwartz is showing me in the pit can have different temperatures, depending on how warm it was the day it fell. The higher the temperature in the snow, the faster it will melt.

"Once that goes above freezing, that's when we can no longer have the snowpack and this is all going to disappear and switch to rain," Schwartz says.

And what's happening to those low temperatures?

The lab maintains the oldest continuous winter weather records in the country. For the month of January, for example, the minimum daily temperature here goes up and down since 1971. However, the 50-year temperature trend rises relentlessly toward 32 degrees, the magic number where snow becomes rain.

"It's climbing. And so, we expect a transition away from snowpack and to rain within the next several decades," he says.

Talking to Schwartz, it's hard for me to wrap my mind around the idea that the Sierra Nevada, over time, will be a less snowy, rainier place. Practically speaking, he says that means incredible challenges are ahead for the people who manage water resources.

Because snowpack levels have become less reliable, officials can longer exclusively count on long-established snow records to predict how much water they should expect from snowpack.

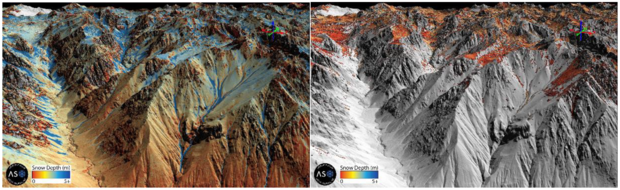

In response, California and Colorado are using new, technology from a company called Airborne Snow Observatories that gives precise measurements of snowpack depth. These images, taken with LIDAR technology mounted on airplanes, creates precise depth measurements and reveal the wild swings in snowpack depth from year to year.

What does the warming winter mean for the snowpack?

"The snowpack is less reliable and more variable than it used to be. And if we're switching back and forth between snowfall and super warm days and snowfall and super warm days, we might not have the chance to really build an efficient snowpack to run off to the agriculture and farmers that need it," Schwartz says.

Doing what you can

Winter weather is most pronounced in places like Minnesota and the Sierra Nevada, but the change in winter doesn't only affect cold weather communities. Many agricultural regions are dealing with these changes, too.

And that's why I find myself drinking wine during the day — for journalism! — with Paul Bush. His family has owned the Madrona Vineyards in Camino, California, for over 50 years.

Paul's telling me consistently chilly winter temperatures are critical to maintaining healthy grapevines. Winter is when vines go dormant, lose their leaves and store up energy to push out a bud for the next year. If it gets too warm, the vines will push out buds during the winter, leaving them vulnerable to frost.

"The earlier you bud, the greater chance you're going to have a problem," Paul says.

Last year Paul faced a stretch of weird winter weather that caused a problem he'd never seen before. In February, it got unseasonably warm. As a result, the vines started to bud. Then came a frost that killed the buds. In March, it got warm again, more buds, another frost. In April it happened a third time.

"It was the erratic roller coaster of temperatures this last fall that I think was the difficult part. Our harvest on the vineyards here, we lost about 70%. That's hard on a small family business," he says.

In addition to grapes in California, fruit crops across the country, like apples, blueberries and peaches, also rely on chilly winters. That didn't happen in 2017 in Georgia and South Carolina, where fruit famers sustained $1.2 billion in losses after an unusually warm winter.

Similarly, a widely-cited 2009 study from researchers at UC-Davis and the University of Washington-Seattle concludes, by the end of this century the climate in California "will no longer support" some of the state's main tree crops like cherries, apples, prunes, peaches, pistachios and walnuts.

"These changes are having a worrying impact, in that we've had a number of 'shot across the bow' winters that have been very significant and shown us what we can expect if we don't change course," said Katherine Jarvis-Shean, Ph.D., a horticulture expert at UC-Davis, who was not involved in the study.

Back at the vineyard, Paul prunes his vines every winter. By cutting away old growth, pruning sends a signal to the plant to put its energy into fewer vines. In response the threats he faces from unreliable winter temperatures, Paul is experimenting with a new technique: delaying when he prunes certain varieties.

Pruning later, Paul says, delays the budding. So, the varieties that are most susceptible to budding out early and getting killed by frost will be pruned last.

"I think that's where all vineyards, all farmers, are learning to adapt to what we can do. And there are certain things we can do and certain things we can't," he says.

Conclusion

I started this journey thinking about our shared pursuit of personal comfort and the lengths we'll go to, to shield ourselves from extremes.

At the end of this journey, though, I'm finding it remarkable how a dip in a frozen lake helped change my focus. Five minutes of discomfort is a trivial amount of time, but the thrill I found in confronting my own limitations has lasted much longer.

From the lakes of Minnesota to the mountains of California, and almost everywhere in between, winter weather is getting warmer and less reliable because of climate change.

It's a loss that blunts the rhythm of the seasons and creates problem for our water supply, outdoor recreation and agricultural yields.

In a more personal way, it's also a problem for you and me.

Even if you never dip into a frozen lake — and I hope you do, someday — losing extremes that push us to our limits means losing part of what it means to be human.

I'd love to hear your thoughts, on Twitter, about the changes you're seeing in winter.