Washington Hotel Site Of Failed Civil War Summit

WASHINGTON (AP) -- The delegates used separate hotel entrances: Pennsylvania Avenue for Northerners, F Street for Southerners.

They shouted, argued and one day almost came to blows before their chairman, a former U.S. president, yelled, "Order!"

Then, the day before Valentine's Day 1861, one of the aged attendees passed away in his hotel room, begging colleagues from his deathbed to save the Union so he could die content.

They failed.

Indeed, there wasn't much peace at all during the "Peace Convention" at Washington's Willard Hotel that winter. And despite the dying wish of sickly old Ohio Judge John C. Wright, his beloved Union was soon torn in half.

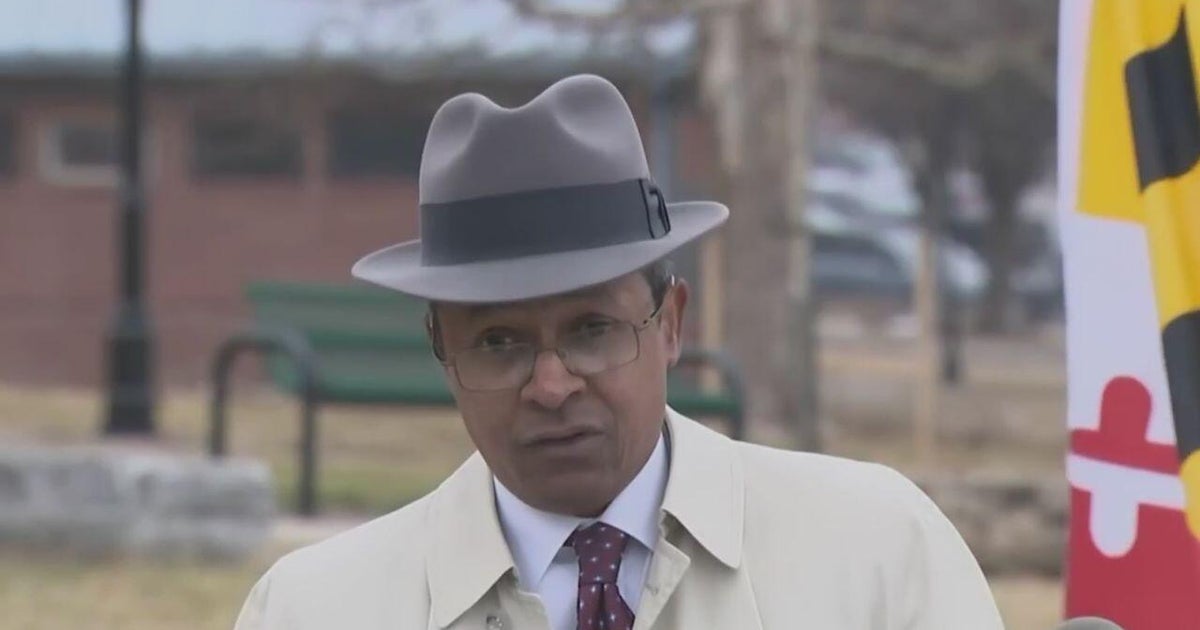

This week, as part of the Civil War Sesquicentennial, historians are gathering at the Willard InterContinental hotel to remember the failed, and largely forgotten, peace conference of 1861.

There, 150 years ago this month, 132 delegates from 21 states bickered, bargained and tried in vain to bridge the chasm that widened beneath them even as they met.

Six weeks after they adjourned, the war began. And the memory of the men and their meeting faded.

But for three weeks that February — the last winter of peace for four years — there was hope among the smoky parlors of the Willard that, as the Washington Evening Star wrote, "the threatening cloud is ... rapidly passing off the horizon of the country's future."

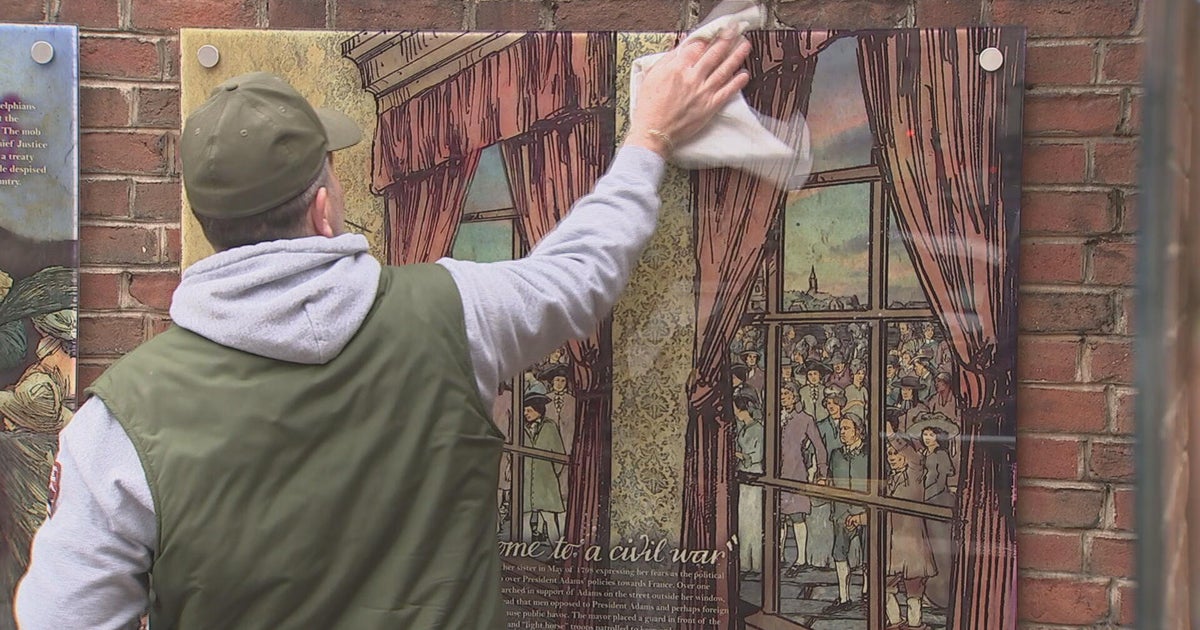

On Friday, a symposium, sponsored by, among others, the Lincoln at the Crossroads Alliance and the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation, is scheduled at the hotel, followed by the dedication of a new outdoor plaque marking the anniversary. An existing plaque dates from 1961.

The Lincoln foundation is scheduled to hold its inaugural meeting at the hotel Thursday, when it will announce its mission, call for proposals and host a reading by actor Stephen Lang of Lincoln's famous "Farewell to Springfield" address.

The 2:30 p.m. plaque dedication is open to the public.

The main focus will be on the peace conference, whose originator, former president John Tyler, told delegates: "If you reach the height of this great occasion, your children's children will rise up and call you blessed."

It was an effort that, in light of events, seemed futile.

Seven states already had seceded from the Union when the convention opened Feb. 4. The small Union garrison at Fort Sumter had been under siege for weeks and was running out of food. President-elect Abraham Lincoln, wary of the convention, was coming to Washington for his inauguration a month later.

But at the time, the gathering had prospects and clout. Its illustrious delegation, headed by Tyler, included an array of elder statesmen and business leaders. And it assembled in what historians say was then the largest hotel in the nation.

On the same spot as the current hotel, the old Willard was blocks from the White House, the Treasury and Newspaper Row, and just down muddy Pennsylvania Avenue from the Capitol.

It was also close to one of the city's red-light districts, where some of Washington's thousands of prostitutes operated, according to Washington historian Cindy Gueli.

"You've got the Willard here," she said. "You've got the red-light district there. You've got Newspaper Row on your left. And you've got all the (government) headquarters on Lafayette Square."

Despite the looming calamity, said Lincoln scholar Harold Holzer, who is slated to speak at the symposium, it's a mistake to view the convention only in light of the war.

"That's looking backwards through the wrong end of the telescope," he said. "The people who met were only trying to reverse the secession of a few Lower South states" and issues related to secession.

"You can't look at it and say, 'We've got to stop this because 600,000 young men are going to die,' " he said. "They didn't know what was going to happen. . . . In that way, they were deluded."

The convention hoped to offer a compromise — mainly about slavery — that would soothe the rebellious states and satisfy the militant northern abolitionists, scholars say.

It also aimed to keep states in the Upper South from seceding.

And the delegates "thought they had time," Gueli said.

The states that sent delegates chose prominent citizens experienced in public affairs.

In addition to Wright, 77, and Tyler, 70, delegates included War of 1812 veteran Gen. John E. Wool, 77; Ohio's former U.S. senator Thomas Ewing, 71; and a former New York Supreme Court chief justice, Greene C. Bronson, 71.

The group also included Felix K. Zollicoffer of Tennessee, a future Confederate general, and Pleasant A. Hackleman of Indiana, a future Union general, both of whom would be dead on the battlefield within 12 months.

Tennessee delegate Josiah M. Anderson would be killed after giving a secession speech the following November. And New York's James S. Wadsworth, the patrician landowner and future Union general, would be killed at the Battle of the Wilderness in 1864.

But all that was ahead.

Three days after the delegates assembled in secret, shielded by police, the Evening Star hoped that under the "happy influence" of the conference, "six months will find every seceded state restored to its allegiance to the Union."

For good luck, the mayor of Washington lent the meeting a portrait of George Washington, according to historian Robert Gray Gunderson's 1961 account of the conference.

Alas, many delegates brought their sectional differences along with their baggage.

"There was a lot of fighting," Holzer said. "They just fought over every procedural issue. Clearly, one side wanted expansion of slavery. One side wanted curtailment of slavery. It was very much like the whole body politic."

Gunderson wrote: "Amendments were appended to amendments and substitutions substituted for substitutions."

The Star reported of the Feb. 25 session, "Today nothing has been done . . . because speech making has monopolized the precious hours."

At one point, veiled insults flew. A brawl almost erupted. Tyler shouted: "Shame upon the delegate who would dishonor this conference with violence."

Wright, who had made the difficult journey from his home in Cincinnati despite chronic bronchitis and failing eyesight, died Feb. 13.

The next day, the delegates put aside their differences as his coffin was brought into the meeting hall for a funeral service.

A letter was read from Wright's son in which the old man pleaded for the preservation of the union so he "would die content."

The delegates then accompanied his body to the railroad station for its journey home.

The peace convention closed Feb. 27 to a volley fired by 100 cannons.

But its proposed 13th amendment to the Constitution was little more than "awkwardly phrased abstractions," according to Gunderson. It essentially perpetuated slavery in the South, barred it in the North and, under certain circumstances, permitted its extension.

It was widely and bitterly criticized. The House of Representatives refused to consider it. In the Senate, shortly before dawn March 4, it was voted down, 28 to 7.

About the same time, Abraham Lincoln, who had arrived in town about a week earlier, was just waking up at the Willard. In a few hours, he would go to his inauguration and himself appeal for peace.

Information from: The Washington Post, http://www.washingtonpost.com

(Copyright 2011 by The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved.)