Teachers, Parents Struggle With New Common Core State Standards

ALLISON BOURG

The Capital

ANNAPOLIS, Md. (AP) -- In Kelly Thompson's household, extracurricular activities are history.

There's no time for music lessons and after-school sports, no matter how much her two children enjoyed them.

Not with the multiple tests her fourth-grader and sixth-grader take each week on top of additional hours of homework, the result of the new Common Core State Standards rolled out in Anne Arundel County Public Schools this year.

"It has completely changed our family dynamic," said Thompson, co-creator of the Facebook group Parental Awareness of Common Core.

The new standards are designed to better prepare students for college and careers, and sound good in theory, she and other parents say. But in practice, they say, the shifting educational tactics have left teachers frazzled, students stressed and parents frustrated.

In June 2010, Maryland became one of the first states to adopt Common Core, which sets national standards in math and language arts. Forty-five states and the District of Columbia have adopted the standards, which were coordinated by the National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers.

Common Core proponents say it establishes uniform benchmarks that can put America on a level educational playing field with other countries.

Opponents call it a federal takeover of education. They say parents were never consulted on the standards, which were forced on teachers too abruptly.

"It's the worst-implemented program I have ever seen," said state Sen. Ed Reilly, R-Crofton, in an interview earlier this month with the Capital Gazette Communications editorial board and staff. "Most of the people I talk to think Common Core is going to bring Maryland down, not raise it."

William Reinhard, a spokesman for the Maryland Department of Education, said the state Board of Education, with the support of then-Maryland school Superintendent Nancy Grasmick and Gov. Martin O'Malley, began talking about Common Core in 2009.

Counties, including Anne Arundel, have been gradually adding elements of the standards to their curriculum since the state adopted them in 2010. All of the counties were required to fully implement Common Core this year.

States that adopt the standards can receive federal Race to the Top grants. In 2010, Maryland received $250 million in Race to the Top money, to be spread over four years.

"From the very beginning, our state board thought this was a good idea," Reinhard said.

He pointed to U.S. students' below-average performance in math on the 2012 Program for International Student Assessment. Results of that test, which measures the academic proficiency of 15-year-olds from 65 different countries, were released last week.

"You only need to look at that to realize our nation lags behind many other nations in these areas," Reinhard said.

Reilly, who sits on the Senate's education committee, said he expects about 20 bills regarding Common Core to be introduced during the upcoming General Assembly session. The measures will include attempts to repeal the program and delay its implementation, he said.

Bob Mosier, a spokesman for Anne Arundel County schools, said it is difficult to estimate how much Common Core is costing this year, in part because the standards have been phased in over the last few years.

The school system got $3.6 million in Race to the Top money over four years for professional development related to Common Core. The state Education Department also awarded county schools more than $600,000 for three summer training academies for teachers.

In addition, the schools got $3.2 million in Race to the Top funds for technology to support Common Core, and $350,000 from the state for technology upgrades.

County schools haven't requested any additional funds for Common Core, Mosier said. It's unknown what will happen next year, when the Race to the Top funding runs out.

Greg Pilewski, assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction for county schools, said growing pains are to be expected with Common Core. Imagine a teacher who has taught for decades having to learn a new way of teaching, Pilewski and others said. Or parents, who learned multiplication tables by memorizing them, having to explain to their children the theories behind the math.

At a meeting about Common Core last month in Severna Park, parents spoke of their children coming up with the correct answers on homework and tests, but not getting full credit because they didn't include an illustration of how they derived those solutions.

Parents like Thompson say their children are struggling. Suddenly, it's not enough to know eight times eight equals 64.

"Is there anything wrong with memorization? I don't think so," Reilly said. He said he has heard from 150 parents who feel the same way. In one instance, Reilly said, a student failed a test, despite having all of the right answers, because he didn't show his work.

Pilewski said teaching children to be critical thinkers "is the essence of Common Core." The standards, he said, were designed to teach students to think beyond rote memorization and regurgitation. So students might be required to draw a picture illustrating how they came up with the answer to a math problem.

Or a book that once was taught in fifth grade is now being taught in third or fourth grade. For example, under Common Core, Laura Ingalls Wilder's "Little House in the Big Woods," typically read in third or fourth grade, is suggested reading in kindergarten and first grade. "The Secret Garden," usually read in middle school, is now suggested reading for fourth- and fifth-graders.

Some parents like these shifts. One is Alice Cain, vice president of policy for Teach Plus, a Boston-based nonprofit that works with teachers in high-poverty schools across the country. She's also the parent of two Hillsmere Elementary School students.

She said she has noticed students are learning certain things earlier than they used to. Her first-grade son is mastering vocabulary that his older sibling learned in second and third grade.

"The bar is being raised, there's no question about it," Cain said.

In Latoya Alexander's first-grade class at Pershing Hill Elementary School, students aren't chided for talking to their neighbor. During a lesson on Chinese culture, Alexander instructed students to "turn and talk" to their peers to discuss similarities and differences between American and Chinese students.

The turn-and-talk method could be seen and heard in several classrooms at the school at Fort George G. Meade.

"It's more student-led discussions, and that's really what Common Core is," Principal Tasheka Green said.

Evidence of the new standards is in all of the classrooms. In first-grade teacher Nancy Graham's classroom, daily goals are spelled out on a chalkboard:

"We will write an informative text in order to convey ideas clearly and accurately."

"We will ask and answer questions about key details to understand the text."

"We will relate counting to addition and subtraction in order to count to 20."

Green, who has been working with teachers to prepare for Common Core since the state adopted it three years ago, said her staff is integrating the standards into the curriculum. A key component, for example, is learning how to cite text-based evidence. So Pershing Hill's physical education teacher, who was teaching yoga, had students read a piece on the benefits of the exercise.

Green said she likes the standards because they elevate expectations for students rather than "teaching to the middle."

School officials said they've heard more complaints and concerns from the parents of younger students.

Robbie Greenspan, a senior at Severna Park High School, said he hasn't seen too many changes in his curriculum, perhaps because he already takes Advanced Placement classes that emphasize critical thinking. Greenspan, who wrote about Common Core for the high school paper, The Talon, thinks freshman and younger students are experiencing the biggest changes.

"I'm not learning how to read or write, or read harder things," he said. "We're still reading Shakespeare."

Interim schools Superintendent Mamie Perkins said last month she supports the standards, but that their rollout has been "rocky."

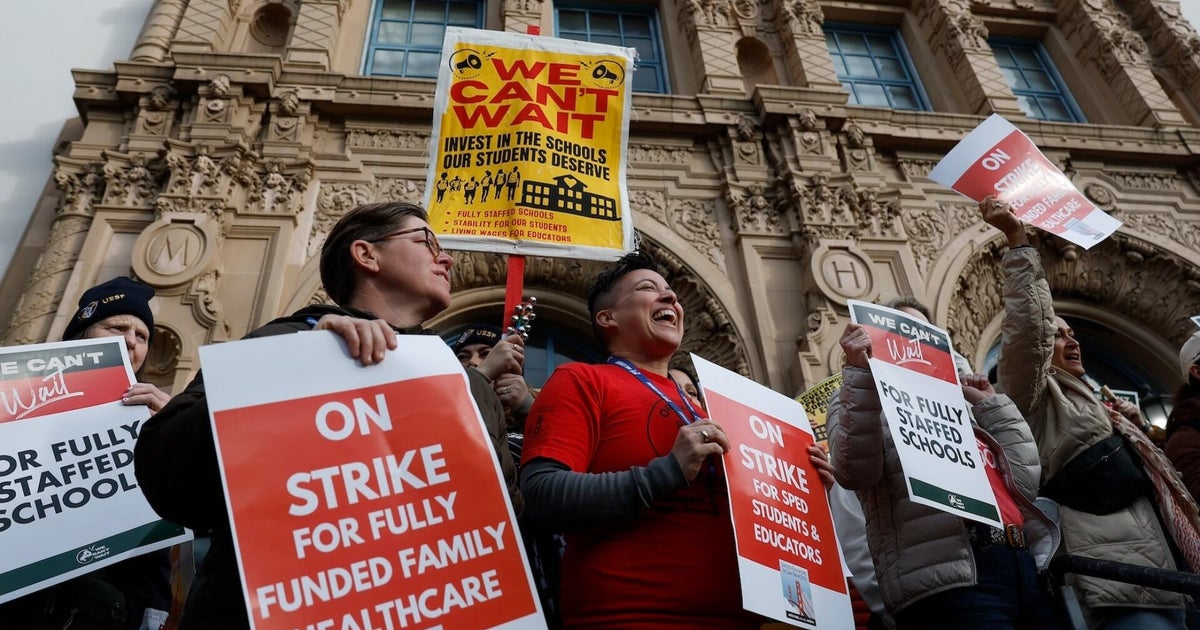

In a survey released last month by the Maryland State Education Association, 86 percent of the 745 teachers polled said they feel "significant challenges" remain to understanding Common Core. Overwhelmed by the unfamiliar standards, teachers are reporting a heavier workload, spending two or more additional hours each week on the new curriculum, according to the survey.

Richard Benfer, president of the Teachers Association of Anne Arundel County, said learning to teach Common Core is "like building a jumbo jet while you're flying it."

Benfer said county teachers have told him they're spending hours devising lesson plans aligned with the standards.

He spoke last month at a hearing before Anne Arundel County's legislative delegation, presenting pages of emails from teachers outlining their concerns about Common Core. One teacher called the math standards "all over the place."

"They give us these things to teach but they are giving us topics that require the students to be fluent in other lessons that should have been taught previously," the teacher wrote. "Problem is that it was not in that grade's curriculum last year."

Cain, the Annapolis parent who works for Teach Plus, said the teachers her nonprofit works with initially felt unprepared for Common Core.

But the more they delve into the theories behind it, the more they like it, she said.

Pilewski said administrators are hearing teachers' concerns and feedback, mostly about not having enough time in the day to plan lessons. There were also some problems with the website teachers use to see Common Core-aligned lesson plans.

Administrators, he said, have formed an advisory group in which teachers can discuss concerns about Common Core. They're looking at adjustments that need to be made within the curriculum.

"Anytime you implement anything new, there are going to be bumps along the way," Pilewski said.

(Copyright 2013 by The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved.)