Schools Adjust To A New Economic Reality

WASHINGTON (AP) -- Officially, the economic free-fall of the Great Recession ended about 18 months ago, but the picture in U.S. schools tells a very different story.

States and school districts have seen their tax bases wither over the past two years, and the financial picture looks bleak for years to come. At least 46 states, plus the District of Columbia, struggled to close budget shortfalls heading into fiscal 2011, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a research organization in Washington.

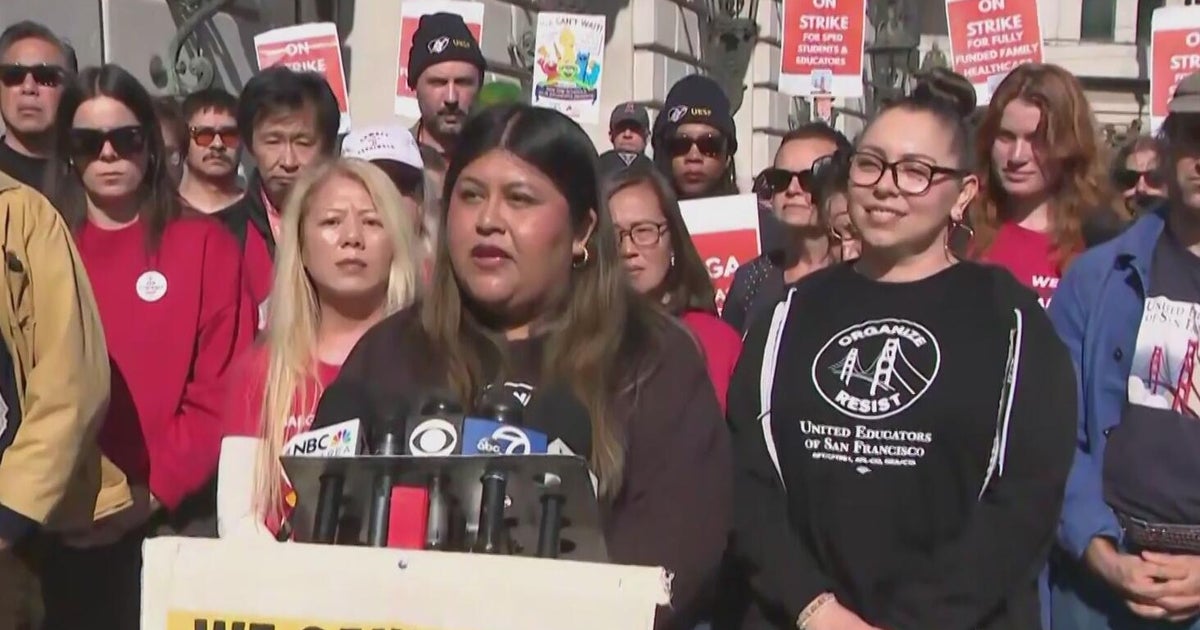

And while political leaders traditionally are loath to cut education programs, even during tough economic times, the downturn's severity has forced state and local officials to make deeper reductions in jobs, programs, and services than they would have contemplated only a few years ago. For example:

- Washington state officials suspended programs to reduce class size and provide professional development for teachers, saving $78.5 million and $15.6 million, respectively.

-

Missouri cut its K-12 transportation funding roughly in half, a move that many school administrators expect to lead to longer bus rides and fewer routes.

-

A number of rural Nevada districts have moved to four-day school weeks, in an effort to save on transportation, personnel, and other costs.

- Virginia cut $341 million in state funding in fiscal 2010 for school support-staff members, from janitors to psychologists.

The pain of such cuts hits home at the schoolhouse level. In Columbia, S.C., the Richland School District Two was forced to cut 45 jobs-including 20 teaching positions-this school year.

"It's heart-rending," says Bob Davis, the chief financial officer, who has more than 30 years' experience as a public and private budget official. The educators who were laid off "loved their jobs, and they're not coming back. ... That's tough. These are the most trying fiscal times I've seen in my lifetime."

Even as the Obama administration has sought to stave off K-12 cuts with emergency aid, U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan has acknowledged that poor economic times are likely to become the "new normal" for states and schools over the next few years.

The challenge for state and district leaders over the next years will be to make choices that address the urgent budgetary concerns facing schools, while meeting long-term academic and financial priorities, says Karen Hawley Miles, the president and executive director of Education Resource Strategies. Her Watertown, Mass.-based organization analyzes district budgets, including money spent on academic courses and staffing, to examine whether spending is aligned with school-improvement goals.

"We don't believe that the conversation is about what to cut," Miles says. "The conversation is, 'What is it that we want to do? What are our most important priorities? And then, how do we organize resources to do that in the best way?"'

The financial duress would almost certainly have been much worse had it not been for an unprecedented infusion of emergency federal aid over the past two years, most notably some $100 billion in education funding through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the $787 billion economic-stimulus package passed by Congress in 2009 at the urging of President Barack Obama.

That money included the $4.35 billion Race to the Top program, which provided competitive grants that encouraged bold policy changes to improve student achievement. The law prompted several states to overhaul their polices in such areas as teacher merit pay and evaluation, data use, and charter schools.

But the vast majority of that money must be spent by the fall of this year-a deadline that leads to what many observers warn is a "funding cliff," at which point states and districts will have to make deep cuts or raise taxes.

Congress gave states additional help last summer, through the approval of a $10 billion Education Jobs Fund, which the Obama administration said would help preserve up to 160,000 jobs in that sector.

Yet all the federal money hasn't made up for the severe loss in state revenue, as existing tax bases have contracted. At least 34 states and the District of Columbia have cut funding to K-12 or early education since 2008, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, which examines the effects of state and federal fiscal policy on low- and moderate-income households.

During tough economic times, policymakers tend to "start on the periphery," and cut school programs and services outside the classroom, says Noelle Ellerson, the assistant director of policy analysis and advocacy for the American Association of School Administrators, in Arlington, Va. They reduce travel, delay equipment upgrades, and target extracurricular activities and art and music programs, as well as after-school and summer-school programs, says Michael Griffith, a senior policy analyst at the Education Commission of the States, a research and policy organization in Denver. Only then, the analysts say, do policymakers move into cuts that could force changes to programs in core subjects, such as reading and math, and affect classroom instruction, such as increases in class size.

South Carolina's Richland School District Two illustrates the difficult choices facing school systems operating in the shadow of the deep economic downturn.

The 25,000-student school system, with an annual general fund budget of about $190 million, has absorbed major losses in state and local tax revenues, leaving it with $3.5 million less to operate on in fiscal 2011 than the previous year.

The district's enrollment growth normally would have required it to add 38 teaching positions just to keep up, says Davis, the chief financial officer. Instead, it was forced to cut positions for teachers and other employees. Other hard decisions await: Next fiscal year, the district will have to do without the $4.6 million in federal stimulus aid it received this year.

The recession began in December of 2007, and it officially ended in June of 2009, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, despite the lingering economic pain. A complicating factor in education's recovery is that recessions typically have a long "tail" that affects school budgets well after other sectors of the economy have rebounded.

One reason for that lag is school districts' dependence on property taxes and the time it takes for property assessments to reflect changes in market value, says Donald J. Boyd, a senior fellow at the Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government, at the University at Albany, State University of New York. State budgets, another key source of school funding, also tend to reflect an economic recovery more slowly than the private sector does, Boyd noted.

As the recession took hold in 2008 and 2008, 33 states attempted to make up for lost revenues by raising taxes, in areas such as personal income, sales, businesses, tobacco, alcohol, and motor fuels, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Yet the new money only carried states so far. States lost more money during the recession-$87 billion in tax receipts-than they made up through new taxes, according to the center. And some states that raised taxes still face major budget woes, in part because the tax hikes they approved were only temporary.

The flow of federal stimulus money, meanwhile, has made an immediate difference in some places, such as the 257,000-student Broward County, Fla., school system. The district, with the help of federal jobs money and other sources, recalled the vast majority of 555 teachers it laid off last year. They included Anthony J. Tabacco, an elementary school music teacher.

Tabacco, 32, was told during the final week of classes during 2009-2010 school year that he wouldn't have a job because of layoffs. He spent much of last summer looking for teaching work, with no luck, until the district contacted him, around the time the federal jobs bill became law, and told him a part-time position had opened up. A different, full-time spot later became available.

"I couldn't believe it. I almost cried," Tabacco recalls. "I know how fortunate I am." At the same time, he's unsure what the future holds. "I don't know if I'll have a job next year," he says, "but I feel better this year than I did last year."

On the whole, government employment, including jobs in schools, tends to be more stable than private-sector employment during a recession, because of the nature of the services provided by schools and other public institutions, says Boyd, of the Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute.

And from a historical standpoint, per-pupil government spending on K-12 education has generally risen steadily since the 1930s, in both constant and unadjusted dollars, federal data show. Some observers say that school budgets have become bloated over time, and that the recent recession could actually bring benefits by compelling district leaders to re-examine how they spend money and to cut unnecessary jobs and programs.

Private-sector employers periodically have to make cuts during tough economic times, and school districts also need to make those hard choices, argues Frederick W. Hess, the director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, a Washington think tank. It's especially important for schools to cut fat from budgets during downturns, he says.

"Nobody likes to make hard choices when times are good," Hess says. But during recessions, states and schools "need to look inward" for cuts that make operations more efficient over time.

For states and districts facing difficult choices, the most effective budget cuts reduce costs and keep them down over time, says Marguerite Roza, who is on leave from her position as a research associate professor at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, at the University of Washington. Unfortunately, many states and districts have sought to lop off expenses through one-time fixes such as furloughs, which bring only temporary relief, as opposed to more politically difficult reductions to salaries and benefits, argues Roza.

With furloughs, "you've done nothing to deal with your expenditure gap in future years," says Roza, who also is a senior economic and data advisor at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

"You've got the same people in the system, the same salaries, and the same service."

A broader question is whether the budget troubles will affect ambitious policy changes in areas such as teacher compensation that are being proposed or implemented across the country. Those pay initiatives have sought to link teachers' compensation to their performance in raising student achievement, among other measures.

Andres Alonso, chief executive officer for the Baltimore schools, says there is also countervailing pressure to leave in place traditional evaluation and compensation models. Late last year, his district and its teachers, after a long negotiation, agreed on a new contract that replaces many traditional salary features based on longevity with a system more heavily based on performance.

"You have the rhetoric of reform and change superimposed on an operational frame which is essentially conservative," Alonso said at November forum on school spending in Washington. "You have a kind of huge gravitational pull toward not disrupting what is there."

(Copyright 2011 by The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved.)