Md. Mom Who Killed Son Agonized Over School Costs

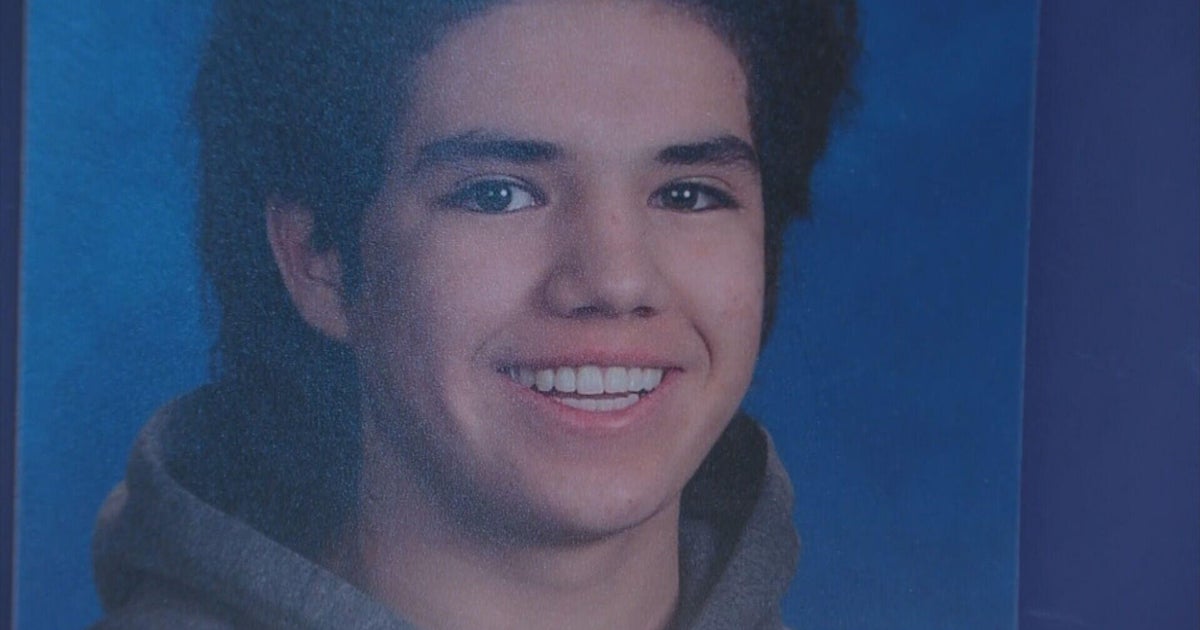

WASHINGTON (AP) -- Ben Barnhard had reason to be optimistic this summer: The 13-year-old shed more than 100 pounds at a rigorous weight-loss academy, a proud achievement for a boy who had endured classmates' taunts about his obesity and who had sought solace in the quiet of his bedroom, with his pet black cat and the intricate origami designs he created.

But one month before school was to start, his mother, psychiatrist Margaret Jensvold, shot him in the head, then killed

herself. Officers found their bodies Tuesday in the bedrooms of their home in Kensington, Md., an upper-middle class Washington suburb. They also found a note.

"School -- can't deal with school system," the letter began, Jensvold's sister, Susan Slaughter, told The Associated Press.

And later: "Debt is bleeding me. Strangled by debt."

Although family members said they were stunned by the killings, they also said Jensvold had become increasingly strained by financial pressure and by anguished fights with the county public school system over the special-needs education of her son, who had an autism spectrum disorder. They said the school district -- apparently believing it could adequately educate Ben -- had refused to cover tuition costs for the boy to attend a private school for special-needs students. Jensvold didn't have the money herself and didn't want to return her son to public school, where relatives

said she felt harshly judged and marginalized and where Ben had struggled.

"It was a huge stress," Slaughter said. "It's very hard being a single parent under any circumstances, but to have a high-needs child is overwhelming. And then to have him inappropriately placed in the school, and have the school fighting with her, was really traumatic."

Jensvold also offered an explanation for taking her son's life.

"She did mention in the note that she knows people whose parents committed suicide when they were children and how difficult and traumatizing that was, and she didn't want to do that to Ben," Slaughter said.

"It is very true," she added. "I can't imagine Ben ever recovering from the loss of his mother."

Special needs education is an emotionally freighted issue, perhaps especially so in Montgomery County -- an affluent region where parents tend to be actively engaged in education and where schools are consistently rated among the country's best.

School district spokeswoman Lesli Maxwell said that privacy laws prevented her from discussing the particulars of Barnhard's case, but that the district offered vast options for its 17,000 special-education students and will refer students for private schooling when it can't meet their needs.

Jensvold, a Johns Hopkins-educated psychiatrist specializing in women's health, was passionate and determined. She made news in 1990 by filing a gender discrimination lawsuit against the National Institute of Mental Health, where she was a medical staff fellow.

A judge ultimately ruled against her, calling her version of events an "illusion." She later had her own private practice but most recently was working at Kaiser Permanente.

She also was a protective mother, constantly fighting with Montgomery County schools over how best to accommodate her son. He was her world, said her divorce lawyer, Robert Baum.

"She came with an album of pictures of her in a very warm and endearing type of situation," he said. "Her arms around him playing outside, amusement parks, all the types of things you'd love to see of parents dealing with their kids."

Ben was an active infant -- his family nicknamed him "ATB," or All-Terrain Baby -- but became increasingly withdrawn and isolated, and relatives said as a child he developed an autoimmune disease that's sometimes triggered by strep.

A divorce court filing lists 18 specialists involved in Ben's care, and Jensvold's own suicide note hints at some of the child's difficulties: "writing problems, migraines, hearing things" -- and "a bit paranoid."

He had a small group of friends and enjoyed computers, origami, animals and picking tomatoes with his grandmother, his father said.

But school was difficult for him, and his weight -- topping 275 before his weight loss-program -- made him a target for teasing. He found comfort with even more food.

"He used to say, `Mom and Dad, I don't want to go to school. I don't want to deal with those people. They're mean to me and they hurt me,"' recalled Jamie Barnhard, Ben's father and Jensvold's ex-husband. "It broke both of our hearts."

The couple placed their son in the county's special education program, but Barnhard said his son struggled in the system.

He spent about nine months at Wellspring Academies, a weight-loss boarding school in North Carolina, returning in May more than 100 pounds slimmer and more confident.

"He wanted to ride his bike. He wanted to be a kid again," Barnhard said. "He wanted to go out and have fun. He wanted to fly airplanes with his dad. He wanted to just do anything."

But there were still concerns about where to send Ben to school.

Jensvold appeared consumed by his education at her father's memorial service last spring, Slaughter said. She confided that she was having trouble paying the roughly $50,000 tuition for Ben to attend Wellspring. She presented a binder about five-inches thick detailing his academic needs, along with a chart showing how his IQ had fallen over the years.

At the end of June, Slaughter wrote her sister to say their mother would pay for Ben's education for the coming year.

Jensvold had planned to enroll her son in the Ivymount School, a Rockville, Md., private school specializing in autism and other learning disabilities. Tuition there ranges based on a child's needs, but can be more than $60,000, the school said Monday. Her mother said she'd send a check.

In her final months, Jensvold only sporadically communicated with her family, as she had for years, Slaughter said.

Emails frequently went unreturned, mail sometimes unopened.

Ben spent July 4 with his divorced parents aboard his dad's restored boat, treading past the Washington Monument with a picnic dinner of barbecue and pineapple. It was a final moment of serenity.

He died a month later. One day after his body was found --co-workers hadn't heard from Jensvold for days and newspapers had accumulated outside the house -- a $10,000 check from Jensvold's mother arrived, Slaughter said.

(Copyright 2011 by The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved.)