Md. Lobbyists, Lawmakers Privately Craft Laws

ANNAPOLIS, Md. (AP) -- Maryland lawmakers will invite wine lovers who want their favorite vintages shipped to their homes to make their case Friday at a state Senate committee hearing. But to influence the bill to allow such shipments, connoisseurs would have done better to attend a pair of undisclosed "stakeholder meetings" weeks ago.

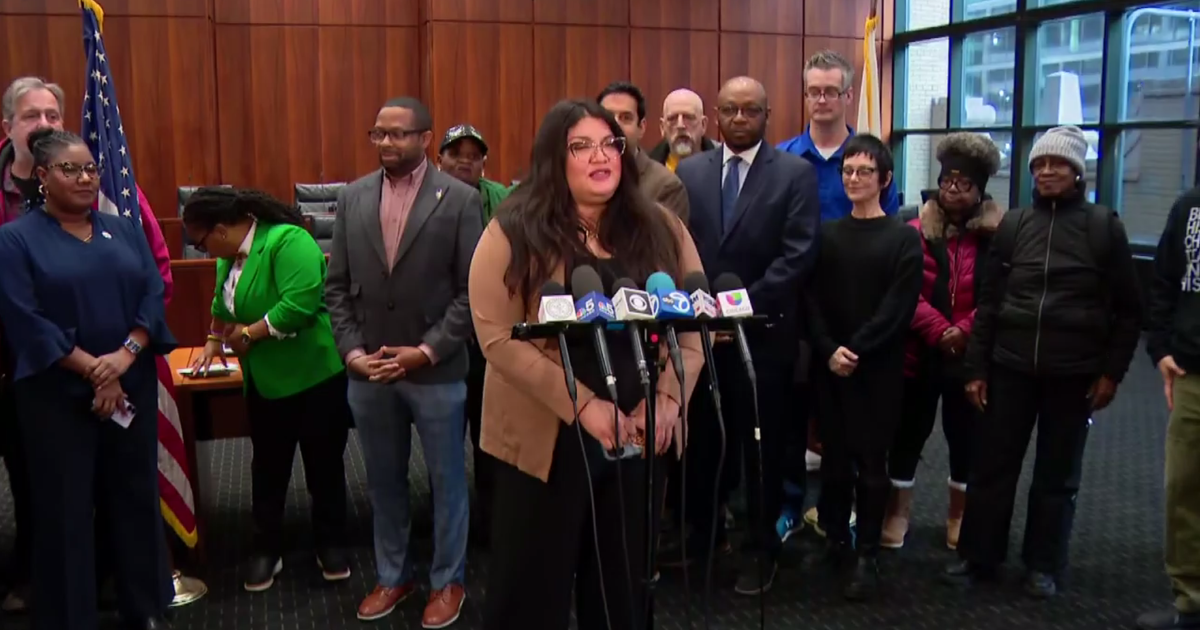

Sen. Joan Carter Conway, D-Baltimore, assembled lawmakers and state alcohol lobbyists for two "stakeholder meetings" on the issue, on Feb. 3 and 15. An Associated Press reporter attended the first meeting, but was kept out of the second meeting.

The secret negotiations that produced the compromise -- which would allow for direct shipping from wineries, but not retailers, including many wine-of-the-month clubs -- is a lesson in how decisions are made quietly in Annapolis, sometimes weeks before the public is invited to weigh in.

"When members of the public get locked out of discussions on legislation, they will rightfully question their ability to influence the outcome of that legislation," said Susan Wichmann, executive director of Common Cause Maryland.

But some lawmakers said such "stakeholder" meetings serve a purpose because they allow interested parties to speak frankly.

"The retailers and the other interested parties wanted to have an opportunity to talk in front of the chair and it's probably easier, to be honest, without an audience," said Delegate Jolene Ivey, D-Prince George's and a sponsor of the wine-shipping bill who was at the Feb. 15 meeting.

Maryland's open-meetings law says the public must have access when a majority of an officially recognized group, including House and Senate committees, meets. It also states that advance notice of such public meetings must be given.

But the law leaves the door open for other meetings between lawmakers and powerful interests.

"Stakeholder" and "workgroup" meetings, as well as other negotiations involving legislators and lobbyists, are commonplace in Annapolis. When environmentalists and developers clashed last year over new stormwater runoff rules, House Environmental Matters Committee Chairwoman Maggie McIntosh convened a series of stakeholder meetings.

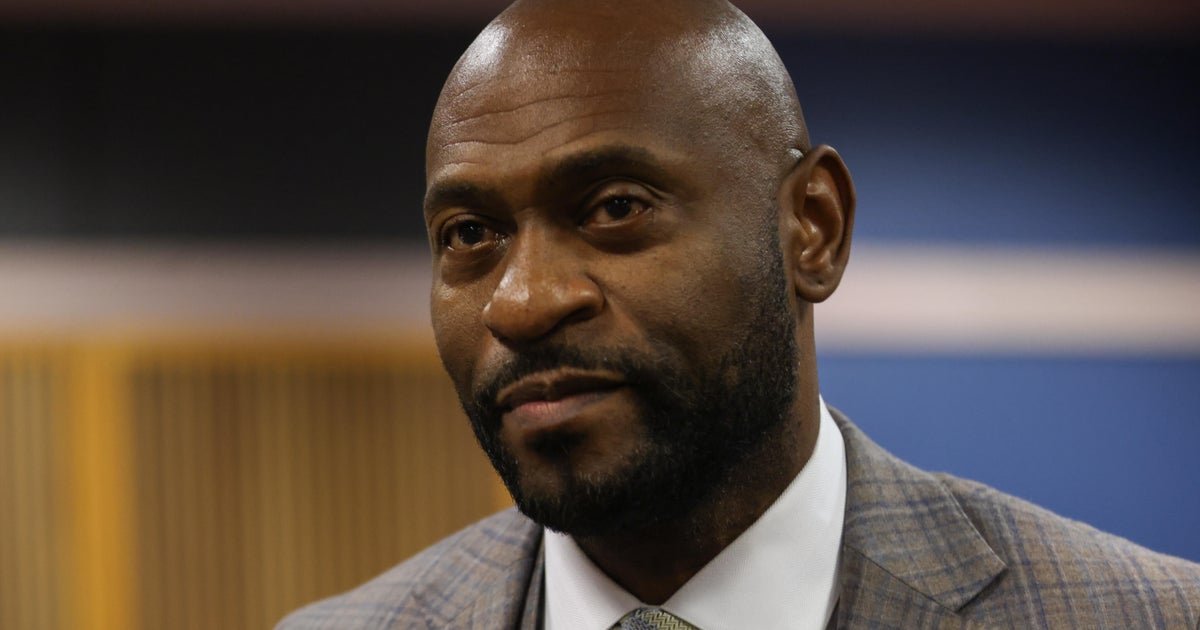

As chairwoman of the Senate Education, Health and Environmental Affairs Committee, Conway will help decide whether Marylanders can get wine shipped to their homes. Advocates of the wine-shipping measure have long had strong support within the legislature, but have battled the state's liquor lobby and committee chairs, including Conway and Delegate Dereck Davis, D-Prince George's, to get committee votes.

For the first stakeholder meeting Feb. 3, the doors to the Senate committee room were unlocked and an AP reporter attended.

Conway and two of the bill's sponsors -- Sen. Jamie Raskin, D-Montgomery, and Delegate Charles Barkley, D-Montgomery, sat at the head of the committee room. Opponents of direct shipping -- including Nick Manis, a lobbyist for the Maryland Beer Wholesalers Association, and Bruce Bereano, a lobbyist for the Licensed Beverage Distributors of Maryland -- sat at the witness table.

Tom Saquella, Erin Appel and two other lobbyists pushing for the wine-shipping bill sat in senators' committee chairs along the right side of the room. Committee staff occupied additional chairs.

Seats reserved for the public and the press were empty, save for the one AP reporter.

At the outset, Conway made a stark promise: A wine-shipping bill will be passed this year, but supporters won't get "the whole cow."

"Let's see if we can get a bill so everyone can stop blaming me," Conway said.

When Conway again assembled stakeholders Feb. 15, the doors to the public hearing room where they met were locked. An AP reporter who requested access was told by a committee staffer who checked with Conway that the meeting was private.

"That's not a public meeting and you're not allowed in unless we say so," Conway told an AP reporter, minutes after the meeting ended.

Not all stakeholder meetings are closed-door or unannounced. But for the ones that are, Maryland's open-meeting laws grant little access, even in a public hearing room.

"What difference does it make? It could be in a bathroom," Conway said of the meeting place.

Dan Friedman, assistant attorney general and legal counsel to the General Assembly, said Conway is "100 percent right."

Maryland's open meetings laws is based on who is gathering and whether they are discussing the public's business, not where they meet, he said.

Maryland's rules are fairly typical of other states, although some, including Colorado and Florida, require open meetings when as few as two lawmakers convene, said Brenda Erickson, a senior research analyst with the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Sen. Bobby Zirkin, D-Baltimore County, held stakeholder meetings before he won passage last year of a measure to require judges to seal records of requests for protective orders that they deny or dismiss.

Some supporters and opponents didn't speak at a public hearing on the measure because it was "too late at that point" to shape the bill, he said.

Zirkin argued that stakeholder meetings help a time-constrained legislature -- the General Assembly's sessions typically last 90 days -- find middle ground.

Adam Borden, who founded Marylanders for Better Beer & Wine Laws , said he learned his lesson.

For two consecutive years, he felt locked out of key discussions in Annapolis as he sought to build support for legalized wine shipping. He coordinated hours of public testimony last year before Conway's committee, thinking he could win with a coordinated push there and strong support from lawmakers. Then, he learned Conway would not bring the measure to a vote, killing it.

"How do you manage hearings when consumers aren't at the hearings where the decisions are being made?" Borden asked.

Borden didn't attend Conway's two closed-door meetings, but he said he is now coordinating with high-dollar lobbyists representing state wineries and the Maryland Wine Merchants Association, who were in the room.

"The deck is stacked against you if you don't work with the established system and players," Borden said. "I don't think it's impossible (to succeed), but I think it's very, very difficult."

(Copyright 2011 by The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved.)