Gardens Help Refugees Connect To New Land

TARA BAHRAMPOUR

The Washington Post

RIVERDALE, Md. (AP) -- Mukti Raj Gurung's last memory of his childhood home in Bhutan is a field of rice, ready to be picked. But his family never got to reap the harvest.

When he was 14, their ancestral farm -- with its rice and corn fields, vegetables, cattle, horses and dogs -- was confiscated under a government policy of stripping ethnic Nepalis of their property and forcing them out of the country. For the next 20 years, the family lived in an overcrowded refugee camp in Nepal, a "suffocating environment" where food was distributed by international aid groups.

It was only in America, where he and his wife arrived as refugees in 2009, that Gurung, now 36, found a piece of what he had lost all those years ago.

As the sun rose last week over a small square of land in Riverdale, he raked the ground to prepare it for planting.

"I have a deep memory of this," said Gurung, whose closely cropped black hair is flecked with gray. Standing barefoot in the dark soil made him feel far away from the camp's pervasive hopelessness. "That's why I come here."

"Here" is one of 17 gardens in nine cities across the United States that have sprung up through New Roots, a program developed by the International Rescue Committee to help refugees reconnect with the land.

"A lot of their skills are not recognized -- they are really undervalued -- especially farming," said Ruben Chandrasekar, executive director of the IRC's Baltimore office. "On a small scale, it's giving people a little bit of an opportunity to grow food for their salad, but on a larger scale, it's an opportunity for people to grow and build a space with what they have."

The IRC resettles about 7,000 refugees each year, around 1,000 in the Washington-Baltimore area. Many come from agrarian backgrounds but have been cut off from farming by war, ethnic cleansing or other upheavals. In the United States, they often end up living in apartments in low-income urban areas known as "food deserts," where the most easily accessible foods are highly processed and loaded with salt and high-fructose corn syrup. Many develop problems with obesity and diabetes.

New Roots began in San Diego in 2009, two years after a group of Somali Bantu refugees asked an IRC representative if they could grow their own food. Working with local partners, the program has spread to New York, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Seattle, Dallas, Charlottesville and Boise, Idaho, in addition to the sites in Baltimore and Riverdale, which came on board this year and last year, respectively. Also, an urban farm will open soon in Pinole, Calif.

More than 400 refugees participate, allowing them to trim their grocery costs and, in some cases, sell their food at farmers markets or to local restaurants and stores.

In almost all the cities New Roots serves, there are more would-be farmers than land to offer them, and this week the organization is launching a new campaign to raise awareness and funding in order to expand.

"I'm hoping by 2015 we can grow a million pounds of food a year, which would more than triple our current production," said Ellee Igoe, technical adviser for food and agriculture for the IRC's U.S. Programs.

This summer, seven families began tending raised beds in the side yard of the IRC's office at the Baltimore Resettlement Center in the Highlandtown neighborhood, traditionally home to immigrants from Eastern Europe and Greece, and more recently Latin America.

"I fundamentally believe that the refugees with a farming background gain some sort of spiritual strength from this kind of work," Chandrasekar said. "It's a way for them to heal from some of the traumas that they suffered. It's a way to bring life out of the earth."

In late August, the Baltimore group held a party to celebrate their first harvest. While a refugee from Darfur strummed a guitar and sang, butterflies fluttered around in the cool shade of late afternoon. Abdi Hassen, 31, showed off his hot peppers, cabbage, tomatillos and eggplant -- ingredients for dishes from his native Ethiopia.

Hassen, an irrigation engineer, arrived in the United States four months ago. He had grown vegetables in Ethiopia but was forced out by ethnic persecution. His father disappeared, and his mother was jailed. Hassen fled to a refugee camp in Djibouti where, he said, "for 10 years, I didn't buy any fruits or vegetables."

Now he is discovering the ins and outs of the mid-Atlantic climate. "I'm not familiar with the weather," he said. "Here, there is an icy season, so I can do short-term planting."

Some refugees are skeptical at first, said Luke Carneal, a Connecticut College student majoring in international relations and an intern at the Baltimore location this summer. "A lot of them come here and say, `I don't know what I can plant here. Can you really grow things in a city landscape?' "

But once they start, even the busiest ones find time to tend to their plants. "It's amazing the amount of time they devote to it," Carneal said.

Chatur Gurung, 28, from Bhutan, studies English in the morning and then rides a bus across town, two to three hours each way, to tend to his ground cherries, vegetables and herbs at the Baltimore site. Smiling, he clasped his hands together. "This is very good for mental health," he said. "And my family makes food from this."

At the Baltimore location, refugees and asylees from Kurdistan, Darfur, Bhutan, El Salvador and Ethiopia have shared techniques for watering, organic pest control and vertical gardening in small spaces. They have also gotten to sample new and exotic flavors.

"I'm going to do some cucumbers," Hassen said as his 2-year-old son, Zakir, hugged his leg. "I was not familiar with it, but now my friend showed me, and I love it."

Participants grow such staples as tomatoes and peppers, but they also focus on their national cuisines. Uzbekis grow Uzbeki melons; Cambodians grow water spinach, a leafy green; and Bhutanese grow bitter gourd and ground cherries, a small tomatillo-like item.

As the Baltimore site enters its second year, "you're going to see a much larger variety of crops as people get family members to send seeds," Chandrasekar predicted.

At the Sheridan Street Community Garden in Riverdale, where the IRC program has two plots, Gurung took a break from his raking and sat cross-legged in the shade of giant sunflowers.

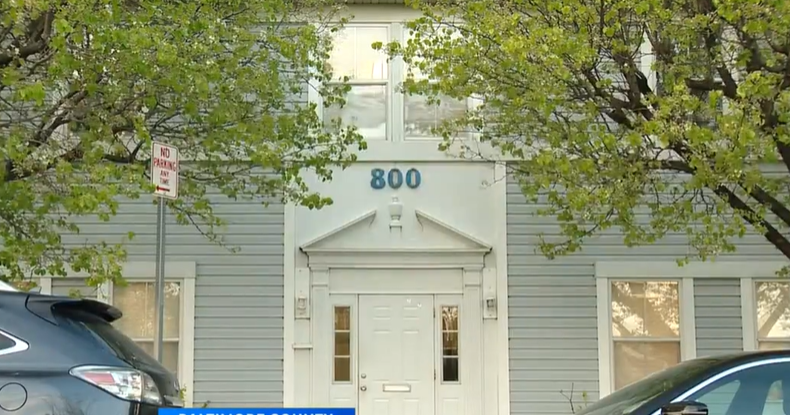

"I never thought America was like this. I used to think America is big cities, crowded," said Gurung, who with more than 30 members of his extended family has resettled in a nearby apartment complex with no yard. He works as a security guard for the complex and is a board member of the Association of Bhutanese in America. Sometimes, he's joined in the garden by friends and family members, including his 2-year-old son, Ashiv, born a few months after Gurung arrived. For older relatives, farming helps alleviate culture shock and isolation.

For Gurung, too, whose first name means "salvation," working the land is a balm.

"To be a refugee itself is a very horrible thing. It's a very sad part of my life," he said, adding that his brother was jailed in Bhutan for 18 years and tortured.

But as the morning sun warmed the soil beneath his feet, he could feel all the possibility of his new life. He said he might eventually start some type of business related to agriculture and the food industry -- something he never could have realized in the camp.

In the meantime, if the warm weather held, there would soon be mustard greens to make a curry.

(Copyright 2012 by The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved.)