Climate Change Is Making Storms Like Hurricane Florence Worse

(CNN) -- Extreme weather events are often pointed to as harbingers of what is to come, thanks to manmade climate change. Unfortunately, Hurricane Florence, like Hurricane Harvey last year, is an example of what climate change is doing to storms right now.

The planet has warmed significantly over the past several decades, causing changes in the environment in which extreme weather events are occurring.

Some are small and inconsequential, and some -- such as increased wind shear that tears apart hurricanes, could actually be beneficial. But there can be destructive consequences.

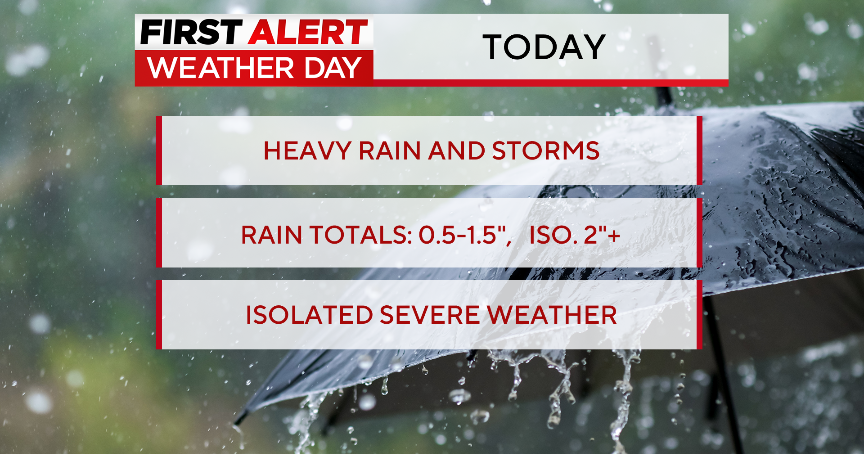

Of the effects we are most certain of, such as increased rainfall and storm surge, Florence is a sobering example of how a warmer planet has worsened the impacts of hurricanes.

Florence's environment was warmer and moister because of climate change, said Kevin Trenberth, a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, and that set the stage for what was to be the storm's biggest threat: heavy rainfall and flash flooding.

Warmer planet, warmer ocean

Human-caused greenhouse gases in the atmosphere create an energy imbalance, with more than 90% of remaining heat trapped by the gases going into the oceans, according to the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association. Ocean heat content, a measure of the amount of heat stored in the upper levels of the ocean, is a key indicator of global warming.

Last year was the hottest on record for the Earth's oceans, with a record high for global heat content in the upper 2,000 meters of the oceans. This year is trending even hotter, with April-June ocean heat content the highest on record.

"The heat fuels storms of all sorts and contributes to very heavy rain events and flooding," Trenberth said.

"The observed increases of upper (ocean heat content) support higher sea surface temperatures and atmospheric moisture, and fuel tropical storms to become more intense, bigger and longer-lasting, thereby increasing their potential for damage."

Warmer oceans mean more moisture is available in a warmer atmosphere.

"It's one of the simplest relationships in all of meteorology," said Michael Mann, professor of atmospheric science and director of the Earth System Science Center at Pennsylvania State University.

For every 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degree Fahrenheit), there is 7% more moisture in the air. Ocean temperatures around Florence trended 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) warmer than normal, contributing to about 10% more moisture available in the atmosphere.

This certainly helped make Florence the wettest tropical system to strike the US East Coast, dumping almost 3 feet of rain on parts of North Carolina.

Higher sea levels, higher surge

Florence brought the tides to record levels in portions of North Carolina despite having weakened to a Category 1 storm, with peak winds of 90 mph Friday morning.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's tide gauge at Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina, surged more than 4 feet above the normal high as the storm was making landfall, breaking a record set by Hurricane Joaquin in 2015 by more than a foot.

Flooding in Beaufort and Wilmington, North Carolina, also topped high-water marks that go back decades.

Several factors combined to make Florence such a prolific coastal flood threat. Its large size, slow movement and previous Category 4 intensity all helped pile up a huge amount of water.

But those characteristics are mainly a product of the day-to-day weather patterns around Florence and are somewhat random -- a roll of the weather dice, if you will.

One important threat enhancer is that ocean levels along the East Coast have risen by nearly a foot in the past century, thanks primarily to global ocean warming.

The added height of the ocean is a reality faced every day by coastal residents, even when storms are not present, such as with sunny-day floods in Miami and the Outer Banks of North Carolina.

But when a storm such as Florence comes ashore, the destruction is even worse than it would have been decades ago -- one reason why Category 1 hurricanes such as Matthew and Florence produced higher water levels on the North Carolina coast than did 1954's Hurricane Hazel, a Category 3 storm when it made landfall in the same region.

Florence and Harvey should not be treated as an example of what human-fueled global warming could bring us at some point in the future. They are unfortunate examples of what global warming, caused by ever-increasing greenhouse gas emissions, is doing to storms in the present day.

Better coastal infrastructure and flood defenses along with an immediate reduction in greenhouse emissions can help minimize the future threat.

President Donald Trump was to get a close-up view of the damage Wednesday when he tours the hardest-hit areas of the Carolinas, just as he did in Houston with Hurricane Harvey last year.

The visit will once again provide the President with evidence that climate change is already affecting the country.

The-CNN-Wire™ & © 2018 Cable News Network, Inc., a Time Warner Company. All rights reserved.